In the mangrove forest mudflats Down Under, a worker ant cautiously extends her antennae. What is the expansive substance before her? Tap, tap, tap. Water! The conclusion is unavoidable: The tide is rising again. To an ant of a different species, such a daunting obstacle might prove insurmountable. Yet, as it happens, this is no ordinary ant. This is a Polyrhachis sokolova Spiny Ant.

The intrepid worker slowly lowers herself into the water, headfirst. As her entire body breaks free from solid ground, she raises her hind feet straight backwards, providing her light body some balance upon the calm water surface. Rapidly engaging her front and middle legs in enthusiastic yet controlled motion, the ant begins to swim. To a human onlooker, the behavior resembles dog paddling. Though, because P. sokolova ants have engaged in this behavior for untold millennia before dogs evolved, it is more accurate to say that swimming dogs resemble ant paddling. Supported by her aquatic abilities, the Spiny Ant traverses the flooded habitat in short order. Arriving safely to the other side, she regains footing on muddy ground and emerges from the water unscathed, merely a mite wetter for wear.

Returning to her colony entrance with a social gut full of food for her nestmates, the ant is confident that her colony is prepared for the continually rising tide. Her species is well-adapted to such challenges, even cleverly engineering nest tunnels with special chambers that form air pockets when the whole nest is inevitably flooded. A mountain of water may come—and a mountain of water will come—but the reproductive queen and her brood will ride out the storm in these pockets of refuge. In due time, the tide will recede. The swimming ant, along with her fellow workers, will resume foraging once again.

Meanwhile, far removed from the Spiny Ant’s field of view, well beyond the potential comprehension of her small mind or the greater collective intelligence of her colony, a new threat rises. Tales of habitat destruction and rising global temperatures float high above the ant’s head, like invisible radio waves traveling at a frequency no insect antenna can decipher. The ominous stories, growing by the day, will soon transform into stark realities for the ant and her nestmates. Alas, the processes of natural selection proceed too slowly to allow adaptation to such rapid development. These striving, swimming Spiny Ants represent a constellation of behaviors, traits, and interactions that evolved over millions, tens of millions, even hundreds of millions of years. Within perhaps one hundred years, in the blink of a mammalian eye, their story will come to a violent end. The threat will have come ashore onto the mangrove forest mudflats Down Under. Will any pockets of refuge remain?

Unlike the adaptable Polyrhachis sokolova Spiny Ant, humans are more than capable of observing and cherishing the evolved variation and stunning beauty with which we share our one Earth. May we marvel at Odontomachus Trap-Jaw Ants and their long mandibles that close with such rapid force they can propel themselves up to 50 times their own body length into the air. May we ponder with humility the Aphaenogaster ants that use tools to transport foraged food more efficiently. May we breathe in the pungent, lemony aroma of Acanthomyops Citronella Ants. May we savor the sweet taste of Myrmecocystus and Camponotus Honeypot Ant replete workers. May we learn from the cooperation of Oecophylla Weaver Ants collectively binding together the leafy walls of their treetop homes using larval silk. May we heed the warnings of Formica Wood Ants as their shifts in behavior foretell of imminent earthquakes. May we feel the interconnectedness between disparate species and ourselves, like a hungry antbird closely tracking an Eciton Army Ant trail in the hopes of feeding on insects flushed out by the foraging column of nomads.

In an increasingly distracted world, the focused desire to conserve nature begins to fade into history. Who among us pines for the unknown? The truth is that thousands of ant species could go extinct as humankind carries on—perhaps unwittingly suffering for the loss of various ecosystem services, yet still falling short of total extinction. To avoid such a fate, it is imperative that we not only relentlessly promulgate the beauty of our fellow creatures, like ants, through direct public education and scientific inquiry, but also create the social conditions that foster exploration and appreciation of nature. The anthropogenic global threats faced by marvels like Polyrhachis Spiny Ants will only ever be properly addressed with a restructuring and reimagining of our current priorities. Union members withholding their labor may proximately fight for fairer conditions in a localized workplace, yet in so doing, they push against a voracious ideology that prioritizes unsustainable growth to the detriment of biological diversity. Religious practitioners of all faiths assert the fundamental importance of the spiritual lives of people, a belief that not only conflicts with a capitalist perspective of people as tools for profit but also opens the door to a deep appreciation of all living creatures as part of Creation, or guides and teachers, or fellow travelers in cyclical and eternal life processes. Activists protesting factory farming galvanize all people towards a more loving relationship with livestock that naturally extends to all life. Through a continuation and increase in all such human efforts, perhaps we can reverse the tide of biological disruption and destruction, restoring the Earth as a refuge for all.

Note: This opening story is a creative telling of the factual lives of Polyrhachis sokolova Spiny Ants. For a vignette about this species produced by BBC Earth, see here.

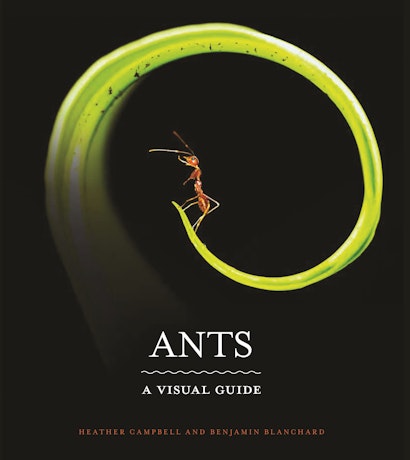

Heather Campbell holds a PhD in ecological entomology from the University of Reading and is a lecturer in entomology at Harper Adams University in Shropshire, UK. She is associate editor for the Journal of Ecology and has written for many leading scientific journals, including the American Naturalist and Myrmecological News. She is a National Geographic Explorer with research expertise in insect ecology, and she specializes in African ant diversity. Benjamin Blanchard holds a PhD in evolutionary biology from the University of Chicago and is a postdoctoral researcher at the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Yunnan, China. His writing has appeared in magazines and peer-reviewed scientific journals, and he is editor in chief of the science blog The Daily Ant. His research expertise is in ant evolution with an emphasis on trait-based diversification.