The nineteenth century commemorated the Protestant hero Martin Luther with giant statues on a host of town squares across Germany. When after 1871 the new German Reich built its massive new cathedral in the heart of Berlin, it placed a huge Luther statue in its line of national heroes. But for the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation, the twenty-first century produced the cute plastic Playmobil Luther that you see above. You can assemble (and disassemble) him yourself and he fits neatly in your pocket. No longer staking a claim to public space, the Luther colossus has now shrunk to kitsch.

If you want to understand Germany and its culture, you have to understand Luther—and particularly because since Brexit, Germany is now the dominant force in the European Union. Martin Luther grew up in the former East Germany and spent almost his entire life there. Luther is anchored deep in the German psyche. You can hear Luther’s speech cadences in today’s German Bible, based on Luther’s original translation, and they echo in the rhythms of even so secular a writer as Bertolt Brecht. Luther’s embarrassingly earthy humour is quintessentially German—and he shaped early German literature with its fondness for the crude. With his deep-set eyes, wayward curl and heavy jowls, Luther remains instantly recognizable—his face is on chocolates, pasta and billboards. The man who loved pork and beer is one of a line of German heroes with gargantuan appetites, through Bismarck to Helmut Kohl who presided over the unification of East and West Germany in 1990. But he isn’t a figure who unites. If it was hoped that celebrating Luther would bring East and West together, in fact the continuing chasm between the two was exposed, a generation after the fall of the Wall. The former East Germany is a resolutely secular society and Protestant church membership is low; it is not as rich as the former West and its politics are different too.

I had published a biography of Luther, Martin Luther, Renegade and Prophet. It took me twelve years to write because I needed to return to the sources—Luther’s biography had become so well-known and so formulaic that if I wanted to say something new I simply had to start again. To my surprise the book became a German bestseller.

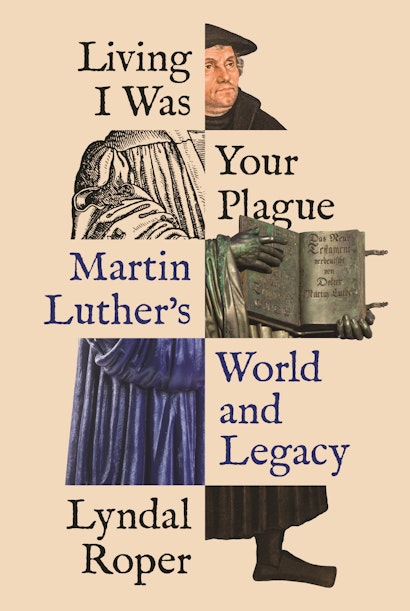

Living I Was Your Plague was written as I travelled around Germany to speak about Luther to a series of very different audiences. Academic authors rarely get to meet their readers: it was an exhilarating and exhausting experience. I was surprised by how much Germans knew about Luther and how deeply concerned they were about his anti-Semitism. I had started the book with a sneaking liking for Luther’s robust male posturing—but it looked much less benign in the era of Trump. I had tackled the anti-Semitism in the biography, but when I preached from Luther’s pulpit in the church with its statue of a Jewish sow suckling Jews whilst a rabbi looks in the pig’s backside, I knew that I had not got its measure. Luther’s anti-papalism too turned out to be deeper and nastier than I knew. He even wanted his curse of the papacy to be his testament: ‘Living I was your plague, dead I will be your death O Pope!’—and he meant it. These words are to be found on many portraits of the reformer, even including those of him on his deathbed. I hadn’t seen them because they are often painted out. And even when they weren’t, I could not see them because I simply did not expect them to be there.

As I began to realise, Luther’s ghost is everywhere in German culture. And that matters outside Germany too: after all, until recent times Germans were the second largest migrant group in the USA. Luther is far more than a religious figure, and he offers a way into understanding what German-ness means and what its legacies are. This nexus of German identity and the figure of Luther is the reason why Luther could not be celebrated in any straightforward fashion: he is inseparable from Bach and the German love of music, he permeates German literature. Yet his monumentality can fit neatly into a pattern of German political leaders, and he has been instrumentalised to celebrate Saxon patriotism, Reich nationalism and East German pride. His virulent anti-Semitism comes too close for comfort.

Luther remains a deeply divisive and flawed human being. But he was also remarkably courageous and a brilliantly creative theologian. He had the determination and bravery not to recant his views when interrogated in front of the Emperor and the representatives of the whole Empire. That example, perhaps even more than his theology, remains inspirational—‘here I stand, I can do no other’.

Lyndal Roper is the Regius Professor of History at the University of Oxford. Her books include Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet (Random House) and Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. She lives in Oxford, England.