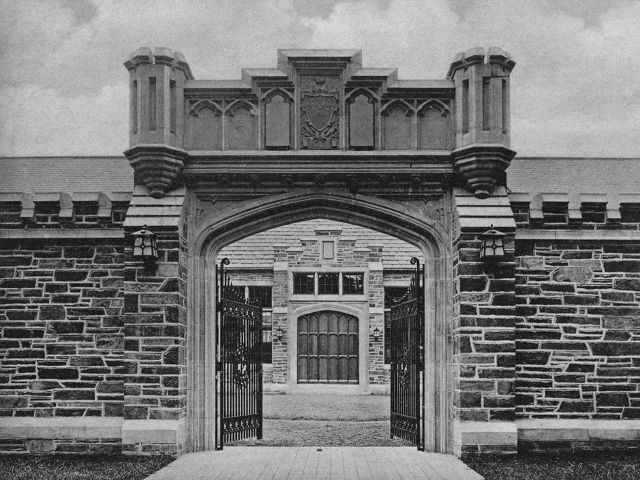

In 1905, when Woodrow Wilson was president of Princeton University, Whitney Darrow, a recent graduate, managed the University’s Alumni Weekly. Because of production difficulties, Darrow saw the opportunity for creating an enterprising press that could assume the Weekly’s printing. Charles Scribner II of the distinguished New York publishing house Charles Scribner’s Sons, who was a trustee of the University, had been considering the need for a publishing company that would issue scholarly books not feasible for commercial firms. Darrow visited him in March 1905, armed with a letter of introduction and a brief proposal. Impressed by his visitor’s pluck and the plan for a press established in the service of Princeton University that would gradually assume the role of publisher, Scribner gave him a check for $1,000. Darrow raised another $4,000 on the basis of Scribner’s endorsement and bought Zapf Press, a local printing outfit. Princeton University Press thus began as a small printer in rented quarters above Marsh’s drugstore on Nassau Street in Princeton, New Jersey. Charles Scribner later gave the Press he founded its land, its building (designed by his brother-in-law, the architect Ernest Flagg, and modeled after the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, Belgium), and a generous endowment.

Unlike most university presses owned or financially supported by universities, Princeton University Press has always been privately owned and controlled. Initially established as a private corporation, it was reincorporated in 1910 as a nonprofit company. Throughout its history, however, the Press has maintained a close relationship with the University: its six-member Editorial Board, which makes controlling decisions about which books will bear the Press’s imprint, is appointed from the faculty of Princeton by the president of the University, and ten of the fifteen members on the Press’s Board of Trustees have a Princeton University connection.

The Press’s areas of publication have shifted and expanded over the years, and continue to be aligned with its founding charter to make available books “for the promotion of education and scholarship.” In its first 25 years, the Press published nearly 400 books. In the 1950s, 45 new books were released each year. Now, in the opening decades of the twenty-first century, the Press publishes approximately 250 new books in hardcover each year and another 90 paperback reprints. The Press’s publications range across more than 40 disciplines from art history to ornithology, computer science to philosophy, and engage readers and listeners the world over.

From 1905 to 1917, when Whitney Darrow was director, the Press developed its printing facilities and began to publish books. Its first book, published in 1912, was a new edition of Lectures on Moral Philosophy by John Witherspoon, the eighteenth-century president of Princeton University’s predecessor, the College of New Jersey. In 1914, when the Darwinian controversy was still alive, the Press published its first best seller, Heredity and Environment by biologist E. G. Conklin. Particularly notable among the early books were those in the Princeton Monographs in Art and Archaeology series, which developed from ties to the University’s distinguished art history department. The Press also published Theodore Roosevelt’s National Strength and International Duty (1917), an intensely nationalistic declaration of the virtues of universal military training.

In the era from 1917 to 1938, when Paul G. Tomlinson was director, the Press built up its printing plant and published 261 books. These ranged from Wordsworth’s French Daughter (1921) by George McLean Harper, which revealed the birth of the poet’s illegitimate daughter, to The Meaning of Relativity (1922), Albert Einstein’s first book published in the United States. Edward S. Corwin’s The Constitution and What It Means Today, first published in 1920, went through fifteen editions and, after he died, was edited by Corwin’s students to reflect new Supreme Court decisions. In 1926, the Press issued J. Franklin Jameson’s The American Revolution Considered as a Social Movement and Robert K. Root’s monumental edition of Chaucer’s greatest artistic achievement, Troilus and Criseyde. During this period, the Press also published Paul Elmer More’s six-volume The Greek Tradition and laid the plans for the Princeton Mathematical Series.

Joseph Brandt, a Rhodes Scholar from Oklahoma, was director of the Press from 1938 until 1941, when he left to become president of the University of Oklahoma. Brandt’s emphasis on publishing heralded a turning point for the Press: during his tenure, publishing outpaced printing as the Press’s primary activity, and the Press made its first efforts to seek out manuscripts of scholarly importance. A twenty-volume edition of America’s Lost Plays and the important Annals of Mathematics series were begun. In addition, the Press published its first novel, Harvey Smith’s The Gang’s All Here, an irreverent satire of college spirit by a longtime Princeton University class secretary.

The Press’s current sense of scholarly purpose derives in large measure from Datus C. Smith, Jr., director of the Press from 1942 until 1952. He created a publishing record and national reputation for the Press and led the Press through its greatest period of growth, issuing 450 books and making the emerging field of international relations a major area of publication in the late 1940s. Among the many books of this era were Bernard Brodie’s Layman’s Guide to Naval Strategy (1942), which was adopted by the US Navy and placed in the library of every American ship (the word Layman’s subsequently had to be dropped from the title); Makers of Modern Strategy, edited by Edward Mead Earle; and the four-volume American Soldier, a landmark publication in the social-psychological study of men at war. But the most significant military book of this period was Atomic Energy for Military Purposes by Henry DeWolf Smyth, the famous “Smyth Report” of the Manhattan Project. This book, described by Herbert Bailey, then the Press’s science editor, as “the literary beginning of the atomic age,” became a best seller with 130,000 copies in print. John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern’s influential Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, Walter Kaufmann’s Nietzsche, Erwin Panofsky’s The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer, and Francis Fergusson’s The Idea of a Theater were also published during this period. In 1950, in a ceremony at the Library of Congress led by President Truman, the Press presented the first volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, a tremendous project conceived by the man who became its first editor, Julian P. Boyd. This series was both a stimulus to the formation of the National Historical Publications Commission and a model for future collections of presidential papers.

After an interval under acting director Norvell B. Samuels, Herbert S. Bailey, Jr., became director of the Press in 1954 (at the age of thirty-two, he was the youngest head of any major university press in the country). Over the next thirty-two years, the Press strengthened its publication program and courageously undertook a number of monumental, long-term projects, most notably The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (a sixty-nine-volume series, edited by Arthur S. Link, which was completed in 1993), The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, and The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. In 1965, the Press built a new 55,000-square-foot printing plant in Lawrenceville, modernized its offices, and launched a paperback publication program that has since become one of the largest among university presses. In 1969, the Bollingen Foundation gave to the Press the world-renowned Bollingen Series, established in 1941 by Paul Mellon and Mary Conover Mellon. Along with this bequest came the responsibility for carrying forward the work of the series in archaeology, ethnology, literary criticism, mythology, philosophy, psychology, religion, and related fields. The one hundred Bollingen volumes include the series The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, The Collected Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and The Collected Works of Paul Valéry. Some of the individual titles include the Collected Poems of Saint-John Perse, the 1960 Nobel Laureate in poetry; Kenneth Clark’s The Nude; E. H. Gombrich’s Art and Illusion; Aleksandr Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, translated and with commentary by Vladimir Nabokov; The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell (which has sold more than 750,000 copies to date); and the Wilhelm/Baynes translation of the I Ching, or Book of Changes (which remains the Press’s single best-selling book, with more than 900,000 copies in print).

In 1986, Walter Lippincott succeeded Herb Bailey as director of the Press. Under his directorship, the Press continued to expand its publication program, increasing the number of acquisitions editors from eight to thirteen, and, in 1993, sold its printing plant in order to focus exclusively on acquiring and publishing scholarly books. The Alumni Weekly also became an independent entity in 1990. The Complete Works of W. H. Auden, edited by Edward Mendelson, was launched in 1989. Other notable books during this period include Brian Boyd’s two-volume biography of Vladimir Nabokov; Robert D. Putnam’s Making Democracy Work; David M. Kreps’s A Course in Microeconomic Theory; Joseph Frank’s monumental multivolume biography of Dostoevsky; and The Nature of Space and Time by Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose. In addition, nine volumes of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein were published by 2005.

Peter J. Dougherty retired as director of the Press in August 2017 and is now editor at large for the Press acquiring in higher education. In his thirteen years at the Press prior to this appointment, he developed a sterling economics list, including such titles as Robert J. Shiller’s 2000 international best seller, Irrational Exuberance; William G. Bowen and Derek Bok’s The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions; Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever’s Women Don’t Ask: Negotiation and the Gender Divide; Joel Mokyr’s The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy; Harold W. Kuhn and Sylvia Nasar’s The Essential John Nash, James L. Shulman and William G. Bowen’s The Game of Life: College Sports and Educational Values; and Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. He brought the editorial vision reflected in this list to his leadership of the Press as it began its second century. On Dougherty’s retirement, W. Drake McFeely, chairman of the Press’ board of trustees and president and chairman of W.W. Norton & Co. remarked:

Peter Dougherty had a visionary plan for Princeton University Press when he took the reins as director 11 years ago. He has executed and expanded brilliantly on that plan, furthering the scholarly publishing mission of the Press while broadening its reach internationally. He has transformed its editorial, management and operational structure, and has still found time to contribute his insights to the larger scholarly publishing community and to continue his own editorial pursuits. The Press has been fortunate in its directors, and Peter ranks with the best of them.

In September of 2017, Christie Henry joined the Press as its current Director. She brings with her 24 years of experience at the University of Chicago Press, most recently as editorial director responsible for managing the acquisitions programs and staff for life science and science studies; economics, political science and law; and reference, which includes the print and digital versions of The Chicago Manual of Style. She is also the first woman to lead PUP.

The Press has always kept pace with the times by strategically evaluating what maintains and sustains long-term success. In 1996, Princeton University Press sold the Laughlin Building, which had housed the printing plant, the accounting offices, and the book warehouse and shipping department. With these operations housed elsewhere, the selling of the building was the last action ending an era of self-contained publishing, a period important to the Press and to the world of publishing at large.

Electronic publishing evolved, in part as a result of the development spurred by the personal computer and the facilitation of communications brought by the Internet. This innovation led to the formation of an in-house electronic manuscripts group, which took on the typesetting of a significant percentage of the Press’s books. Building on the expertise accrued within that group, the Press now has a digital production group, which no longer handles typesetting but oversees the production of ebooks, the digital book program for backlist titles (the Princeton Legacy Library), and such pathbreaking endeavors as the Digital Einstein Papers.

There have also been changes over the decades in the way the Press sells its books. The growth of large independent stores in the eighties, the coming of the superstores in the nineties, and then Internet bookselling at the end of the nineties all expanded the market for University Press titles. Princeton, along with the other large university presses, moved swiftly into this new marketplace. The Press formed a sales consortium with the University of California Press in 1988 to sponsor in-house sales representatives, who call on the college stores, independents, these new chains, and the major wholesalers who resupply the stores. During the 1990s, as an increasing proportion of Press income came from a few top accounts such as Amazon, Borders, Barnes and Noble, and the wholesalers Ingram and Baker and Taylor, the number of field reps was reduced and in-house coverage among the major accounts increased. Beginning in September 2016, the Press has joined the MIT Press and Yale University Press in establishing a new joint US sales team to renew our commitment and better serve independent bookstores, museum bookstores, and specialty retailers.

The focus of the Press moving forward was to acquire an international presence by building on the reputation of its first ninety years. In the late 1990s, the Press opened its European office in Woodstock, outside Oxford, England. This move internationalized the editorial operations and provided an opportunity to attract the best authors in the United Kingdom and Europe in economics, finance, and mathematics—and, more recently, in the humanities. A Publicity/Marketing manager was hired to increase the visibility of this new initiative. Since then the European office has grown to ten colleagues, variously dedicated to editorial acquisitions, foreign rights, and publicity.

While enhancing its national and international presence, the Press also addressed a local issue: the need to renovate the Scribner building (ca. 1911). In response to staff growth and Princeton University’s desire for an updated look to the back of the building, 12,000 square feet of new office space were added. The renovation, which took more than two years to complete, has visual appeal matching that of the University’s Wallace Social Sciences building, Friend Center for Engineering, and Shapiro Walk.

Over the years, Princeton University Press has won many honors. In 1950, the Press received The Carey-Thomas Award of Publishers’ Weekly for the initiation of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. The Press received another Carey-Thomas Award in 1973 in recognition of the accomplishments of Bollingen Series and a third one in 1976 recognizing the Lockert Library of Poetry in Translation. Six Princeton University Press books have won Pulitzer Prizes: Russia Leaves the War (1957) by George F. Kennan; Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (1958) by Bray Hammond; Between War and Peace (1961) by Herbert Feis; Washington: Village and Capital (1963) by Constance McLaughlin Green; The Greenback Era (1965) by Irwin Unger; and Machiavelli in Hell (1989) by Sebastian de Grazia. The Press won a National Book Award for Kennan’s book, as well as for Anthony Kerrigan’s translation of The Agony of Christianity and Essays on Faith by Miguel de Unamuno and for Jackson Mathews’s translation of Monsieur Teste by Paul Valéry. Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky: The Years of Ordeal, 1850–1859, won a National Book Critics Circle Award in 1985. The History and Geography of Human Genes by L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, and Alberto Piazza won the Association of American Publishers’ R. R. Hawkins Award in 1994 for the best scientific, technical, and medical book published in the United States. In addition, the Press has won five Bancroft Prizes for books by Kennan, Arthur S. Link, R. R. Palmer, and Felix S. Gilbert. The Press also has received many awards for excellence in design and printing, including forty-eight honors from the American Institute of Graphic Arts for books designed by P. J. Conkwright, the Press’s chief designer and typographer from 1939 to 1970.

Princeton University Press continues to produce award-winning books at the outset of its second century. In 2005, the Press celebrated numerous prestigious awards alongside its centennial: On Bullshit, by Harry G. Frankfurt, one of the Press’s all-time best-selling books, was a winner of the 2005 Bestseller Awards, Philosophy Category, The Book Standard. Elisheva Baumgarten’s Mothers and Children won the 2005 Koret Jewish Book Award in Women’s History, conferred by the Koret Foundation and the National Foundation for Jewish Culture. The 2005 Silver Medal for the Arthur Ross Book Award sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations was awarded to Stephen Biddle’s Military Power. Joseph Dumit’s Picturing Personhood won the 2005 Diana Forsythe Prize, sponsored by the American Anthropological Association. Also in 2005, the Victoria Schuck Award of the American Political Science Association went to Saba Mahmood’s Politics of Piety; the Victor Turner Prize in Ethnographic Writing, sponsored by the Society for Humanistic Anthropology, was awarded to Bill Maurer’s Mutual Life, Limited; and the Robert E. Lane Award, sponsored by the Division of Political Psychology of the American Political Science Association, was conferred on Kristen Renwick Monroe’s The Hand of Compassion. In 2006, Philip E. Tetlock’s Expert Political Judgment won the Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award of the American Political Science Association.

The ensuing decade has witnessed the publication of a steady stream of new and important titles that have been met with similar acclaim, both mainstream and scholarly. The Poison King, by Adrienne Mayor, and The Eternal City, by poet Kathleen Graber, were National Book Award finalists in 2009 and 2010, respectively, while 2016 saw Beth Shapiro’s How to Clone a Mammoth and Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s The Ruined Elegance selected as finalists for the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes, and Colm Tóibín’s On Elizabeth Bishop nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff’s This Time Is Different, published in 2009, became a New York Times best seller and earned a host of honors, including the 2010 TIAA-CREF Paul A. Samuelson Award and the 2011 Gold Medal for the Arthur Ross Book Award of the Council on Foreign Relations. Peter Brown’s 2012 history of wealth in the early church, Through the Eye of a Needle, glittered with decorations in its turn, collecting several awards from the Association of American Publishers, as well as the Gold Medal for the 2012 Book of the Year Award in the history category from ForeWord Reviews, the 2013 Jacques Barzun Prize in Cultural History from the American Philosophical Society, and the 2013 Philip Schaff Prize from the American Society of Church History. Jeremy Adelman’s biography of Albert Hirschman, Worldly Philosopher, was widely acclaimed and won the 2014 Joseph J. Spengler Best Book Prize of the History of Economics Society; and the 2015 Christian Gauss Award of the Phi Beta Kappa Society, conferred on James Turner’s Philology, marks the third the Press has received in the past ten years.

Among all these honors, however—and many more far too numerous to mention here—perhaps the most remarkable testament to the work the Press has been doing, and continues to do, is the number of scholars who have published with the Press and subsequently gone on to win Nobel Prizes. Since the turn of the millennium alone, no fewer than seventeen Princeton authors have been plucked off the list to be created Nobel laureates, in literature and, with astonishing frequency, in economics. J. M. Coetzee (The Lives of Animals, Landscape with Rowers) and Mario Vargas Llosa (The Temptation of the Impossible) were awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003 and 2010, respectively, while George Akerlof (Animal Spirits, Identity Economics, Phishing for Phools) and Angus Deaton (The Great Escape) bookend a nearly unbroken succession of Princeton-published winners of the economics prize from 2001 to 2015. The Press is proud to have played a part in bringing these major, influential voices and ideas to the world stage, and looks forward to continuing to change the conversation thus for years to come.