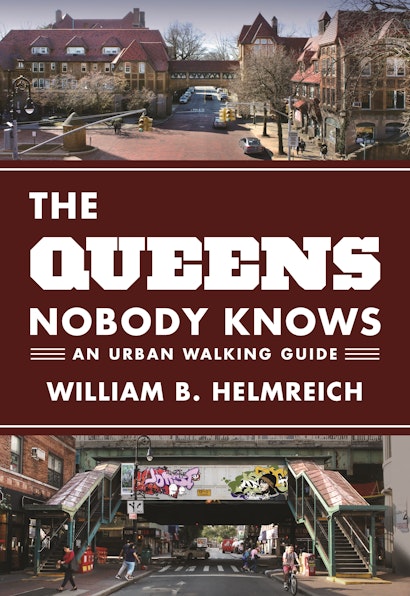

Bill Helmreich (1945–2020) walked every block of New York City—some six-thousand miles—to write the award-winning The New York Nobody Knows. Later, he re-walked most of Queens—1,012 miles in all—to create this one-of-a-kind walking guide to the city’s largest borough, from hauntingly beautiful parks to hidden parts of Flushing’s Chinese community. Drawing on hundreds of conversations he had with residents during his block-by-block journey through this fascinating, diverse, and underexplored borough, Helmreich highlights hundreds of facts and points of interest that you won’t find in any other guide.

Of the sixty-five million or so visitors to New York City every year, the overwhelming majority spend their time only in Manhattan. Because of Brooklyn’s cachet as a destination, a certain number will also include it in their itinerary. Queens remains something of a mystery to most visitors, a place that they know is part of the city, but that might not be of particular interest. Queens was named in 1683 by the British in honor of Queen Catherine, wife of King Charles II. It’s ironic, really, that most visitors see Queens as they arrive, albeit from the air, as their plane circles the borough before swooping down to land at Kennedy, LaGuardia, or another nearby airport. But as soon as they land and collect their bags, most head for the nerve center—Manhattan. Manhattanites, too, can see Queens quite easily. From the East Side, they can view communities like Hunters Point and Astoria, and beyond, but rarely think of them as places worth exploring.

This book, which is part of a series whose focus is on the unknown aspects of New York City, is an attempt to change this dynamic, to open up for visitors a place that is endlessly fascinating and has far more to it than most people realize—from its history to its architecture, its communities, and its individuals. Of course, to its 2.3 million or so residents, Queens is very well known. After all, they live there. But their knowledge is often limited to the communities in which they reside rather than to the borough as a whole.

Queens contains some fifty-seven distinct communities spread out over about 109 square miles. It has some very high-quality cultural centers, beautiful parks, and attractive residential neighborhoods. It has a throbbing nightlife, with clubs, restaurants, and entertainment of all sorts. In Astoria, there’s Steinway Street with its hookah lounges and ethnic restaurants. In Jackson Heights, restaurants and clubs from more than a dozen Latin American lands line Roosevelt Avenue, competing for the affections of both Latinos and others interested in Latin cuisine and music. Just off Roosevelt, on Gleane Street, there’s the Terraza 7 Jazz Club. They host many world-famous performers from a dozen countries, with affordable prices. Along Thirty-Seventh Avenue and its side streets in the 70s there are eateries serving Indian, Bangladeshi, Nepalese, Afghani, Tibetan, and Filipino food. Other parts of the borough in places like Sunnyside, Forest Hills, and Bayside hum with activity as well, especially on the weekends.

In part because it’s so spread out, Queens lacks a clear identity and defies easy categorization. There’s astonishing variety in so many areas—art, architecture, nature, entertainment, foods, and more. It also has an incredible array of ethnic and racial groups. Finally, its residents possess a very strong sense of community. One of the borough’s essential characteristics is how varied and unique it is in terms of what there is to see. For example, far away from the central core of Queens, which lies within easy reach of Manhattan, in the community of Bellerose, there’s a museum within Creedmoor Psychiatric Center devoted exclusively to the art of the mentally ill, the only sizeable one in the United States. Touring the museum I meet a man who creates objects made entirely from coat hangers—a giant sunflower, a detailed guitar, and more. Another paints large murals combining different aspects of the civil rights and antiwar movements of the 1960s.

Further evidence of variety exists in nearby Little Neck, site of the city’s only functioning historical farm, a 47-acre plot of land where fruits and vegetables are grown, and where sheep, cows, and some friendly llamas graze. Adjacent Douglaston is home to the city’s tallest tree. It’s a 450-year-old specimen, a tulip tree that tops out at 133.8 feet. Finding it isn’t easy as it’s in a densely wooded area. In Springfield Gardens, a good ten miles from here, lies a pristine wilderness, on the edge of a sleepy neighborhood, called Idlewild Park Preserve. It’s a wild area of woods, marshes, and fields, filled with chirping birds, small mammals, and fish, a veritable Shangri-la and perhaps the most isolated spot I’ve ever seen in this city, save for some parts of the Staten Island Greenbelt.

One of the last taxidermists in the city, John Youngaitis, has a storefront located in Middle Village. Close by, there’s an opportunity to grab a beer at Gottscheer’s German tavern in Ridgewood, a holdover from a century ago, one of the last in the city. And then it’s on to the Underpenny Museum, an exquisite space crammed with thousands of items based on the idiosyncratic interests of its creator, a Korean immigrant named John Park Sung. Included are a collection of cast-iron trivets from the nineteenth century; hundreds of eggbeaters; mechanical piggy banks, created to encourage children to save money; shaving mugs; snuff bottles; miniature houses; and much, much more.

I also explore the house in which Madonna lived in Corona, a former synagogue and Jewish school, which still has Stars of David set in bricks. The story of how and why she ended up there is a truly intriguing one. In Astoria, one can view the oldest home in the United States. In Addisleigh Park, a subsection of St. Albans, one can walk by the still-standing homes of great musical artists like Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, and James Brown, as well as sports giants like Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, and the one white person among them, Babe Ruth. But that’s another story, also told here. The former home of the founder of Pan-Africanism, W.E.B. DuBois, sits anonymously, on a one-block street, sadly forgotten and neglected.

As to ethnicity, Queens is home to more ethnic groups than any other borough, with residents speaking close to 150 different languages. All in all, it’s probably the most diverse urban area in the world. Some of the largest groups are the Chinese, Indians, Koreans, West Indians, Mexicans, Irish, Italians, and Jews. But there are other groups too, like the Tibetans, Filipinos, Paraguayans, Ghanaians, and Nepalese. These groups are most often concentrated in one geographical area, and a visit to where they live often feels like a trip to the country from which they originated.

A walk along Liberty Avenue in Richmond Hill reveals block after block of clothing, furniture, and jewelry stores, all of them catering to the needs of the Indo-Guyanese community. Navigating the side streets, one sees many homes with the traditional clusters of multicolored prayer flags in their front yards. In another part of the same community one comes to the section where the Sikhs live. Entering their temple on a Sunday morning, one can hear the haunting strains of their religious songs as hundreds of men and women sway to the music. For Sikhs it is a religious commandment never to cut one’s hair. Doesn’t it grow too long? I wonder. A turbaned man tells me, “On my head it stops growing after a time. And my beard, I show you—I roll it up.”

A stroll through Flushing’s Chinatown is a special experience. It is one of the largest and fastest-growing Chinatowns in the world, with new people constantly arriving. The number of Chinese living there, both legal and undocumented, is estimated at about eighty-five thousand. As I wander through the area, I see almost no one who isn’t Asian, and almost everyone is speaking an East Asian language. Street vendors hawk their wares, mostly in Chinese, and crowds on the main avenues make them almost impassable at certain times of the day. I pass by Maple Playground and see four young men kicking, soccer-style, a small butterfly-shaped object. The game is called jianzi, and it originated thousands of years ago during the Han dynasty.

In another part of Flushing, the most ethnic community in the borough, I enter, on Bowne Street, the famous Indian temple, dedicated to the elephant deity, Ganesh. Made of granite and intricately carved, it must be seen to be fully appreciated, especially at night when a kaleidoscope of bright colors from large moving searchlights envelops it. Not far away is an Afghan community and another made up of Malaysians. In Astoria, I observe ethnic succession in real time, as the Greek community recedes and is replaced by a Muslim population, many of them Egyptians and Yemenis. One can visit the LGBT community in Jackson Heights and learn about the Rastafarians in Springfield Gardens. And in one neighborhood over in Cambria Heights it’s possible to stand by the grave of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, revered by millions around the world. Those who love magic will find Houdini’s grave and the story behind it in the section about Glendale. And music lovers will be delighted by the discussion about the Steinway Piano Factory, still operating after 150 years in Astoria.

What’s truly amazing is how well these groups get along with one another, notwithstanding occasional discord. Some of them have long histories of tense relationships between them, like Pakistanis and Indians or Muslims and Jews.

It turns out there isn’t one overarching explanation. Rather, it’s a combination of factors. First, Americans, as a nation of immigrants, celebrate ethnicity, notwithstanding their apprehensions about certain groups, whereas Europeans want newcomers to assimilate. Second, in New York City, conflicts between nations or religions are seen as something that’s happening far away. Those living here are far more interested in problems of unemployment, housing, and crime. As I heard over and over again: “There’s no room for hatred here. We’re all trying to make it.” Most important perhaps, the sheer number of groups tends to reduce conflict because when everyone is “new,” then being new is no big deal. In fact, it’s almost irrelevant. People also seem to welcome the opportunity to make friends on neutral territory with people they wouldn’t ordinarily even meet.

Within the realm of ethnic groups lie some unusual patterns, for lack of a better term. For instance, ethnic succession doesn’t always mean whites being replaced by Asians, blacks, or Hispanics. For example, in Bayside, Koreans are “replacing” blacks because they are willing to pay higher prices for homes. In Jamaica, a Bangladeshi woman explains why she has deliberately moved into a Chinese part of Flushing. She doesn’t want to be restricted to her own group. In Holliswood, a rigorously Orthodox Jewish family becomes close friends with a lesbian couple, who have a lifestyle that the Orthodox Jews frown on. The Jewish family even takes care of the couple’s kids when the couple go away for a weekend.

In addition to ethnicity, Queens has a strong sense of community. New Yorkers of all backgrounds tend to see living with other groups as an opportunity to get to know each other. I remember walking down a street in Woodhaven, a community filled with minorities from Asia and South America, where almost every house had an American flag flying in front of it. In a white working-class community, this wouldn’t attract much attention since displaying American flags has become synonymous with a conservative viewpoint of America. But Woodhaven is filled with immigrants, and this block was no exception. Spying two Guyanese men chatting in front of a home, I asked them why they were flying the flag.

“Because,” said one, “a man on the block gave us the flags and asked us if we would put them in front of the houses, and we thought it would look nice.” That person turned out to be Paul Kazas, a white man who lives on this street. In all, thirty-six homes now fly the flag. Another home owner, a Bangladeshi immigrant, told me that Kazas was so nice he couldn’t refuse, especially when the man offered to replace or repair, free of charge, any damaged or missing flags. Kazas is an attorney and a dyed-in-the-wool community activist. He has also been honored by Congress for his volunteer work. He fixes street malls and prunes trees, and this was his way of engendering pride in being an American. In his words, “I tell them the flag unites us all, and they relate to that.”

In my walks I witnessed examples of civic pride. Queens residents take tremendous pride in their communities. When they’re asked where they’re from, their first response is far more likely to indicate Jamaica, Forest Hills, Astoria, or Douglaston than Queens. When they reminisce about having grown up in Queens, they often exhibit great fondness about what that was like for them. They are also active in the local organizations that represent them—neighborhood and block associations, social clubs, houses of worship, and the like. The borough has a steady stream of parades, ranging from the Memorial Day parades in Little Neck and Broad Channel, to the annual Sikh parade in Queens Village, and the gay pride parade in Jackson Heights. And there are block parties everywhere. This is true of Brooklyn and the other boroughs as well, but here the practice struck me as even stronger and more ubiquitous. The communities are so far away from the central city that they develop a self-image of being a collection of small independent villages.

Another example of strong communal involvement is the hundreds of streets and vest-pocket parks named after residents who gave of themselves to the community, like Bud Haller Way in Glendale, named after a longtime resident. In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy many people opened their doors to neighbors, even strangers, whose homes were damaged, or donated clothing and food. Scott Lowry, a Brooklyn businessman, delivered hot meals to people living in the Rockaways. Such generosity of spirit often crosses ethnic lines. Ghanwatti Boodram was a nurse from Guyana who died in 2009 when her house in Floral Park exploded because of a gas leak. The Boodrams were involved in neighborhood groups, and their children were enrolled in the local public schools. Hundreds of mourners attended the funeral, and people, many of them white, collected more than a thousand gift cards to help family members rebuild their shattered lives.

What of the future? What will happen to Queens in the next twenty years? The city’s failure to come to an agreement with Amazon that would have brought jobs to the borough’s residents was a blow in the view of many, but a victory in the opinion of others. It’s too early to judge what the long-term effects will be, but it’s a reminder of how complex things can get when interests, ideology, and politics collide. As Brooklyn fills up with gentrifiers, Queens begins to look more and more attractive to some members of this varied group of displaced Brooklynites. The prices are lower than in Brooklyn, and the core neighborhoods, those nearer Manhattan, are very accessible via public transportation. And this pattern is becoming clearer with every passing day. Hunters Point is today a forest of glass-and-metal apartment towers resembling elongated spaceships, and Astoria is following suit, as is Ridgewood. But will this extend to the next ring of communities, like Forest Hills, Rego Park, Kew Gardens, and Glendale? To some extent yes, because there are subway lines that reach these areas. But those communities beyond that circle—Douglaston, Bayside, Little Neck, Fresh Meadows, Floral Park, Bellerose, and so on—will attract such people only if transportation improves dramatically.

Then again, it doesn’t have to happen. These communities are, so to speak, full. It’s a seller’s market as largely East and South Asians are snapping up every home on the market in northeastern Queens, most of which belong to retired whites departing for sunnier climes. The same holds true for southeastern Queens, where Caribbean blacks are purchasing homes in predominantly black middle-class areas. There are private homes and garden apartments in these sections, and those who live in them love the relative peace and quiet that prevails. The neighborhoods are quite safe, and affordable housing is available for those who need it. Hispanics are also moving into eastern Queens, but most are still in Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, and Corona, with those who are better off settling on Long Island and in other parts of the metropolitan area.

Regardless of what happens, Queens remains a great place to explore. This borough is one where both natives and immigrants are busily engaged in living in America. This introduction only scratches the surface of what Queens has to offer. To learn more, dive into this book and find out what surprises are in store for the curious and adventurous.

* * *

My love for walking the city can be traced back to a game my father played with me when I was a child, called “Last Stop.” On every available weekend, when I was between the ages of nine and fourteen, my dad and I took the subway from the Upper West Side, where we lived, to the last stop on a given line and walked around for a couple of hours. When we ran out of new last stops on the various lines, we did the second to last, and third to last, and so on, always traveling to a new place. In this way, I learned to love and appreciate the city, one that I like to call “the world’s greatest outdoor museum.” I also developed a very close bond with my father, who gave me the greatest present a kid can have—the gift of time.

In walking, actually rewalking, Queens, my approach was the same as when I did the research for The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6,000 Miles in the City, a comprehensive analysis of all five boroughs. I walked and observed what was going on around me, all the while informally interviewing hundreds of people. New Yorkers are a remarkably open group if approached in a friendly and respectful manner; no one refused to talk to me. Sometimes I told them I was writing a book, but much of the time I didn’t need to, and I simply engaged them in casual conversation. I often taped what they were saying, using my iPhone function in front of them. Hardly anyone asked why, and if their attention lingered on the phone, I explained why I was recording. No one minded. Perhaps that’s a statement about what we’ve become—a society accustomed to cameras and recorders, and one that assumes that few things are really private anymore. Clearly, this is a great boon for researchers. Greater tolerance in general and an abiding belief that the city is safe are also contributors to this state of affairs.

I walked in the daytime, at night, during the week, on weekends, and in all seasons, in rain, snow, or shine, from mid-October 2016 through February 2018. I averaged about 72 miles a month. I attended parades, block parties, and other events and also hung out on the streets, in bars and restaurants, and in parks. Most of the time I walked alone, but sometimes, my wife, Helaine, and, on occasion, our dog, Heidi, accompanied me. I began in Little Neck and finished in Astoria, walking through every community for a total of 1,012 miles, as measured by my pedometer. I had, of course, walked almost every block in the borough for the first book, and probably sixteen times before that, albeit more selectively. I wore Rockports, in my view the world’s most comfortable and durable shoe.

Although I’d already walked nearly every block in Queens, the findings here are almost all new because the city is constantly changing. New stores, murals, and buildings go up, parks change, and there are different events every year, like concerts, comedy shows, protests, parades, feasts, and town hall meetings. Everyone with whom I spoke was new, and the conversations often led in different directions. Walking is, for my money, the best way to explore a city. It slows you down so that you can see and absorb things and literally experience the environment as you talk to those who know it best, the residents. And the more you walk, the greater the chance you’ll get really good material. You just can’t know whether you’ll meet that special person or see an exquisitely beautiful private garden in the first or the fifth hour of your trip on any given day. Bicycling is the next best option.

This book is intended to be a guidebook for those wishing to explore Queens. Because the intended audience here consists mostly of tourists, curious residents of these neighborhoods, nostalgia seekers who grew up in or lived in these areas, and New Yorkers looking for interesting local trips, the book discusses in detail every single neighborhood in Queens. In order to make it a book that could be easily carried around it was necessary to limit the discussion to what I saw as the most interesting points, but there’s much more to see.

The focus is on the unusual and unknown aspects of these neighborhoods. The book is largely a combination of quotes from conversations with residents and reflections on life in general, plus many anecdotes about all manner of things. And its focus on sociological explanations of why things are the way they are combine with all the rest to make it what I believe is a rather unique guidebook.

There’s a street map for each community, and you can walk it in any order you’d like, searching out whatever moves you.1 What was chosen is meant to whet your appetite, to entice you into wandering these streets on your own, where you’re also likely to make new discoveries. Most of the borough is quite safe, with crime rates way down, though you might want to exercise caution in some areas. They’re identified in appendix A in the back of the book, along with some tips on how to safely explore them.

The areas are divided into ten groups of communities and are arranged in this book according to contiguous sections of Queens. You can, nonetheless, walk the borough in any order you choose. There’s some historical information in the sections, but it is admittedly brief. This is, after all, a book about the present. Queens has many famous residents, past and present, a few of whom are noted here. If that’s your area of interest, I suggest looking them up on various sites by Googling “famous residents of Queens, NY,” or going directly to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queens. Some sites actually provide addresses and other details. And if you’re interested in specific topics like parks, the Italian community, or bars, you should definitely consult the comprehensive index at the end of this book.

The vignettes, interviews, and descriptions have one overall goal—to capture the heart, pulse, and soul of this magnificent borough. Naturally, whether or not this has been accomplished is for you, the reader, to judge.

This is an excerpt from The Queens Nobody Knows by William B. Helmreich.

William B. Helmreich (1945–2020) was the author of many books, including The Manhattan Nobody Knows, The Brooklyn Nobody Knows, and The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6,000 Miles in the City, which won the Guides Association of New York Award for Outstanding Achievement in Book Writing. He was Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the City College of New York’s Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership and at CUNY Graduate Center.