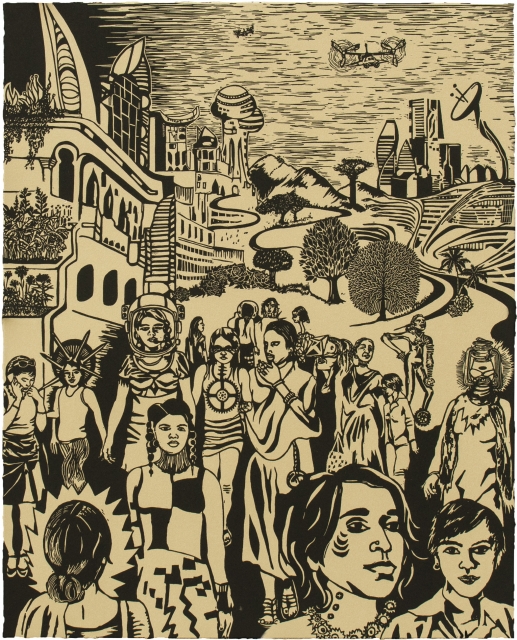

What if we lived in a society where women had the power to make the world anew? What would life look like today if women played a definitive part in governance and had the resources to create sustainable lives? These dreams were imagined in 1905 by Calcutta-based Bengali Muslim writer Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain in her short story “Sultana’s Dream.” Scholars have regarded Hossain’s social vision as an idealized utopia. In her story, Hossain tells of a place called Ladyland, where women reign supreme in public while men are secluded at home. The women of Ladyland are safe in public space and free of modern disease. They divert intellectual and material resources away from the military to create new scientific inventions that regulate the environment. Through this world of women, Hossain creates alternative possibilities for politics and social progress for a colonized society.

I turn to Hossain’s story more than a century after its publication at the end of my book, Indian Sex Life: Sexuality and the Colonial Origins of Modern Social Thought (Princeton University Press, 2020). Hossain’s vision of social autonomy and political liberation for Indian women, relegated to the realm of fantasy, stands in stark contrast to the anti-colonial nationalist visions of the Indian social progress advanced by upper-caste Hindu men. Their anti-colonial visions of liberation and social futures centered on the control and erasure of women’s sexuality. The patriarchal fantasies of men in colonial India were made into reality in the emerging disciplines of social thought across the domains of law, forensics, social science, and popular literature. I ask: why is Hossain’s story relegated to the domain of fiction and fantasy while the fantastical patriarchal visions of Indian men were institutionalized in structures of governance, forensics and policing, and social science in postcolonial South Asia? What if we were to pursue a radical feminist agenda of peaceful futures and scientific innovation based not in violence but sustainability?

Indian Sex Life tells the story of how ideas of women’s sexuality shaped modern social thought in colonial India. I make visible a complex edifice of knowledge that saw racialized ideas of women’s sexual deviancy as the primary way in which one could think and write about Indian society. I reveal how colonial administrators and Indian men built entire fields of knowledge about people in the colonized world on the control of women’s sexuality, often through the concept of the “prostitute.” These structures of social scientific knowledge, built on the control and erasure of women, have an enduring presence in postcolonial South Asia.

The significance of this history of sexuality and social thought resonates across South Asia today, in the gendered violence that is a defining characteristic of rampant majoritarianism and militarized violence in border regions. This history shapes debates about the prevalence of sexual violence against minority and subjugated women and sexual minorities. In these discourses, girls and women are blamed for acts of sexual violence by social and religious leaders, politicians, the media, and even by patriarchal courts endowed with the power to protect women. Narratives of sexual deviancy and social degradation have reemerged most recently in postcolonial India in a new set of anti-Muslim laws against inter-religious marriages between Muslim men and Hindu women that control women’s sexuality through the language of women’s vulnerability, patriarchal state protection, and the sexual danger of Muslims.

We need a new vocabulary for social life to dismantle the patriarchal bounds that shape structures of knowledge that we use to study the lives of women and sexual minorities. Indian Sex Life follows in the rich scholarly traditions of anti-colonial and women of color feminisms, confronting and defiantly undoing the deeply gendered and racialized biases that have shaped how we envision the present and future of our societies. We must radically reimagine how we categorize and narrate gendered lives in the language of modern social thought and theory. I build on Indian Sex Life in my current book, which documents the long legacy of these patriarchal histories of knowledge and the ways women scholars in the decolonizing world reimagine the modern study of women. Half a century after Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, Third World and women of color feminists enacted their own radical feminist visions by arguing that women were complex subjects whose labor and ideas must be valued and studied.

In the twenty-first century, women are bearing the brunt of rising patriarchal authoritarianisms, global anti-Black and anti-migrant racisms, and the violent social fracturing that has resulted from the seemingly never-ending COVID-19 pandemic. We face a monumental crisis unfolding before our eyes, where millions of women of color and women across the post-colonized world are losing and leaving employment because of unequal structures of gendered labor at home and at work. In this moment, the defiance and labor of women and sexual minorities has never been more critical, in vibrant women’s marches from around the world, new global movements for transgender and third gender rights, and in women-led social movements against sexual violence, exclusionary citizenship laws, and anti-Black and anti-immigrant racism. Nothing is clearer than the fact that women and sexual minorities are driving the history of our present. And nothing is more urgent than finding a more expansive language to study, understand, and transform the many dimensions and histories of these lives and ideas.

Durba Mitra is assistant professor of studies in women, gender, and sexuality at Harvard University and Carol K. Pforzheimer Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute.