By 2020, 58 percent of bars that catered to LGBTQ+ people in London had shuttered, leaving just 53 venues in this global capital city of finance and culture.

In the United States, an average of 15 gay bars closed every year from 2008 to 2021, with 50 percent boarded up by the end of the period.

Richard Morgan puts the numbers into perspective: “In 1976, there were 2,500 gay bars in the United States; today, there are fewer than 1,400 worldwide.”

As a result of these closures, the gay bar, championed by researchers as the “primary social institution” of queer life in the 1950s and 1960s, is described by the media today as being in “trouble,” “under threat,” and possibly an “endangered species.”

Why are gay bars closing?

AG: Not all gay bars are the same. And so, if there are many types of gay bars, then there must be many reasons why some of them are struggling. I say “some” to emphasize that not all gay bars around the world are threatened. Those that have folded faced a variety of challenges, some unique to a particular place, others more widely shared.

In London, the two most common reasons why venues closed are both economic. The first reason is redevelopment, which is to say that the land became more valuable than the business. That’s when a developer comes along, buys the business, razes it, and puts up something like luxury flats. The second major reason for the closures involves failed lease negotiations due to rent hikes. Ben Campkin and Lo Marshall from UCL wrote a report that goes into more detail. It’s available online, if readers want to learn more.

How did you find your way to London?

AG: It was an accident. [laughs]

When I had a sabbatical in 2018, a friend invited me to join him at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where he was a member of the faculty. I had no plans, either specifically or vaguely, to study anything there. All I knew was that I loved London—I always have, for reasons I cannot entirely explain. And so I went, deciding in the spirit of serendipity and fate to follow the feelings. Maybe nothing would come of it. But then, you don’t need a spoiler alert to know what happened. In the course of making myself at home, I got invited to a party. Next thing you know, I’m knee-deep in a study!

What motivated you to write this book once you arrived in London?

AG: One day after work—I think it was a Tuesday or Wednesday, a rather ordinary day in the middle of the week—I went to the pub with friends. Someone I had just met, in our banter, suddenly said to me, “Wait a minute. You’re South Asian and queer?” “Yes,” I replied quizzically. “Why do you ask?” And then they asked, “What are you doing Saturday night?” In that quotidian moment, in a quintessentially British setting, there was the invitation that changed everything.

That Saturday night I found my way to an event that featured Bollywood imagery and music. I felt the vibe immediately as I stepped inside a cavernous room. It was an hour’s train ride from the city center where I was staying. Projected on a bare white wall in front of the DJ booth I saw clips of iconic Bollywood videos: Devdas, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, and Khabhi Kushi Kabhie Gham were pulsating on a packed dancefloor. The place felt less gay than queer to me, a compositional and tonal shift fitting for a party called Hungama, an Urdu word that loosely translates to a celebratory chaos or commotion. That was my first experience at a club night. What I felt in that moment was nothing like the alarmist headlines I was reading in the papers about the alleged death of queer nightlife.

If death is an inexact metaphor, what do you propose?

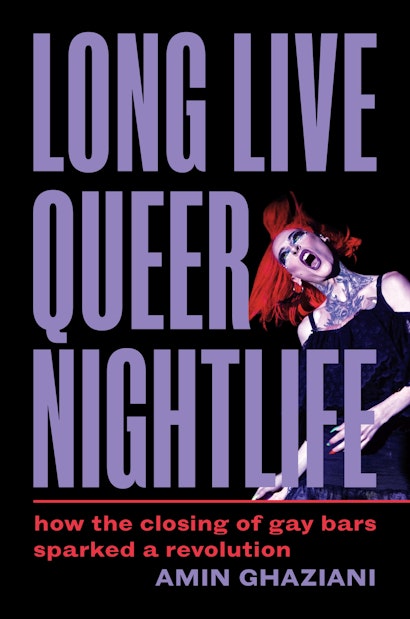

AG: Gay bars are closing in large numbers in many places around the world. That much is true. In my new book, Long Live Queer Nightlife, I argue that those closures are disrupting the field of nightlife and consequently encouraging the visibility of other forms of fellowship. The idea and image of a disruption is shared among organizational, social movement, and cultural sociologists, and I import it into nightlife studies to explain—and celebrate—the emergence of club nights.

A disruption is an unsettled moment of time, either anticipated or unexpected, that alters our routines and the ideas we take for granted. Recent examples include economic recessions, pandemics, mass shootings, and natural disasters. Sometimes, disruptions exacerbate existing inequalities, like racial profiling, which increased following the September 11th attacks in the United States. A reaction like this happens because disruptive events feel urgent, and those of us who are affected by them are compelled to respond right away. But the problem with rapid responses is that they often target survival and they seek a return to the familiar.

As an example, I once read an article in the Evening Standard in which the mayor was talking about saving London’s iconic club scene. In the disrupted environment of pub closures, his office sees a problem of organizational decline. Their goal is to address the threat as quickly as possible and get things back on track. While rational in that it reduces uncertainty, this particular policy response is prone to what researchers call isomorphism. To wit: the mayor’s office assumes that the survival of nightlife scenes is contingent on the replication of a specific form, like the gay bar. Drawing on management studies that show isomorphism can stifle efficiency, I argue that it also conceals creativity—both cultural, in terms of the worldmaking efforts happening at club nights, and organizational, in terms of the institutional expressions of nightlife.

In short: nightlife is not dying; it’s evolving. In contrast to the fixed-place model of gay bars, club nights like Hungama are event-based. They thrive on improvisation, and they favor mobility and intermittence over permanence. At a club night, no one’s mourning the death of the gay bar; they’re busy being the life of the party.

Can you measure the change?

AG: We sure do love numbers! [laughs]

The ideas that I am sharing with you are easier said than studied. For example, tallying the bar listings in travel guides, like Damron or Yelp or Time Out, has been favored method in the literature for decades. While imperfect, like all data, tracking changes in bar listings can establish statistical trends. That said, counting bars only lets us make conclusions about bars—leaving other forms of nightlife, the kinds that are harder to quantify, unexamined.

Hence a caveat that I must offer to readers: there is no comparable data about club nights. I cannot tell you how many events happen every month or every year in London or in any other city for that matter, and I cannot present a precise distribution of the places where these parties occur. Club nights are hard to quantify—but I don’t think that really matters. This world is intentionally inchoate, purposely undefined, and joyfully celebrated as such. The people who produce and attend these parties are there to imagine new ways of being and new worlds of belonging—not new ways of counting.

Are club nights unique to London?

AG: Not at all! Far from atypical, what’s happening in London is part of a global trend. In Toronto, there’s Jerk, a biannual party that follows the influence of the Caribbean on club cultures. In an interview with the media, the organizer, Bambii emphasized a lack of representation in nightlife scenes. This is an important cultural characteristic of club nights that I also discovered in London: they are reclaiming and recentering nightlife on those people who for too long have felt excluded from gay bars. Often, though not always, this means curating space for individuals who identify as queer, trans, Black, Indigenous, and as people of color—QTBIPOC groups, for short.

In LA, there’s QNA, an event that celebrates the queer Asian-American and Pacific Islander community. The organizers told the media that see themselves as part of a transnational network. “QNA isn’t the first time queer Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders have created their own space, demanding to be seen, heard, and celebrate themselves. In the past few years alone, the community has incepted a series of events that have been steadily garnering attention: Bubble_T in New York City, Rice Cake in Vancouver, New Ho Queen in Toronto, and Club Koi in Miami.”

Whether in London or LA, New York or Miami, Toronto or in my home city of Vancouver, these events are drawing on a long and rich legacy. Rochella Thrope describes the rent parties that Black lesbians organized in postwar Detroit, while Marlon Bailey illuminates the Ballroom scene in the early 2000s. Bailey’s interest is in examining HIV and AIDS, especially public health interventions that were designed to contain the infection among Black queer people in order to keep the so-called “general population” safe. The problem with models imposed from outside the group is that they define minorities in biased ways—hence categories like “at risk” or “communities of risk.” Bailey calls for a shift from intervention to intravention as a way to describe how people who are marginalized by multiple vectors of power draw on local knowledges to help themselves. I love the idea of an intravention.

But unlike the balls that Bailey describes, club nights are not just responding to a hostile heteronormative world, to things like racism from the government, but also to hostility from within LGBTQ communities, to things like racism and femmephobia in gay bars. For example, one study found that 80 percent of Black respondents, 79 percent of Asian respondents, and 75 percent of South Asian respondents experienced racial bias from within LGBTQ communities. In my mind, this makes club nights uniquely a refuge from the refuge. They are more intentionally inclusive and intersectional than gay bars and previous historical iterations of event-based nightlife forms.

You’re trained as a sociologist, but you address an issue that humanists also care about. What are your thoughts about disciplinary voice and multi-disciplinary collaborations?

AG: Studies about nightlife often focus on fixed places like bars and pubs. As a result, nightlife is cordoned off to specific parts of the city, like a gayborhood, and our knowledge replicates the traditional scenes of those places. I’m inspired by research coming out of the humanities that refuses to examine nightlife in such institutionally isomorphic ways. Humanists don’t use that language, of course—but this is precisely how sociologists can use our disciplinary expertise to make a unique contribution to an interdisciplinary conversation. This is the beauty of the dance between disciplinary voice and interdisciplinarity: alternative though generative perspectives about ideas that we, in common, love.

What is one big thing that you would like readers to take away from this book?

AG: When I spoke with people about club nights, they used exuberant words, like euphoria, ecstasy, freedom, sanctuary, romance, and utopia. What I heard in London, and what I felt while I was doing my fieldwork, inspired me to think about the importance of joy in our work.

I have lost count of the number of studies I have read about suffering and social problems. Those arguments are accurate, and they’re absolutely essential for guiding us toward a more just world, but having fun and feeling joy is what sustains us while we grapple with the tough stuff. stef shuster and Laurel Westbrook, both sociologists, call this a “joy deficit.” When we singularly focus on what makes life miserable, all the things that make it pleasurable vanish from view.

I think we need to insist on joy—not as something distinct and disconnected from a world in which there is suffering but as a collective salve to it. Anything but trivial, joy is life-enhancing and deeply political. When we go out and have fun with our friends, important things are happening. Those moments create a shared emotional energy that promotes group pride, communal attachments, and new cultural understandings. Joy brings us closer together, and as it does, we model positive relationships with each other.

Moments of joy can also bloom into a broader politics that, according to José Esteban Muñoz, can move us “beyond romances of the negative and toiling in the present.” He says that “we must dream and enact new and better pleasures.” Join me on a dancefloor, and you too may discover the radical, imaginative, generative potential of joy.

Amin Ghaziani is professor of sociology and Canada Research Chair in Urban Sexualities at the University of British Columbia. He is the award-winning author of The Dividends of Dissent, Sex Cultures, and There Goes the Gayborhood? (Princeton). His work has been featured widely in international media outlets, including the New Yorker, the Financial Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Guardian, USA Today, and British Vogue.