In the acclaimed television series, The Good Place, the main characters come to learn that in over 500 years, no one has avoided going to “the bad place” after their death. Why is even the most virtuous of humans not deemed worthy enough for eternal salvation? Because of their consumption choices.

In the capitalist, profit-maximizing market, consumer goods carry the weight of untold human and ecological suffering. A shopper choosing a tomato at the supermarket may think they’re making a responsible, healthy choice. Instead, as a result of the way tomatoes are grown, harvested, and transported, the shopper is unwittingly contributing to problems as far-reaching as climate change, biodiversity loss, and toxic burdens on marginalized workers. As Ted Danson’s character in the show explains, “Humans think that they’re making one choice, but they’re making dozens of choices they don’t even know they’re making.”[1]

To the best of my knowledge, there is no grand point system tallying up our good and bad deeds, but the mindset that consumer choices can either mark someone as vile or virtuous is surprisingly common. The individual who consumes with the planet in mind—by purchasing organic products, growing their own food, having solar panels on their home, and driving an electric car—constitutes what I call “the ideal environmentalist.”[2] In my interviews with a wide range of people in Washington state, and in my survey of Americans in all 50 states, I found a great deal of evidence of this ideal environmentalist in contemporary culture.

Because of the ubiquity of this ideal and the way evaluations of it varied across lines of class and political ideology, I came to see that the ideal environmentalist plays an overlooked and outsized role in polarizing Americans’ responses to environmental issues and their proposed solutions. Broadly, the ideal environmentalist most closely reflected how upper-class liberals exercised their relationship with the environment. That group of people tended to believe that those who don’t consume conscientiously are either selfish (if they’re rich) or ignorant (if they’re poor).[3] Upper-class conservatives were antagonistic toward the ideal environmentalist, accusing those who vote with their dollars for a greener future of being hypocritical: “Who is Leonardo DiCaprio to tell me not to use plastic water bottles when he has a private jet?” Lower-class liberals aspired to emulate the ideal environmentalist. They overlooked their own negligible impact on the environment and blamed themselves for not being able to make a financial sacrifice to go green. And lower-class conservatives expressed skepticism toward the sort of point system that is portrayed in The Good Place. They saw this approach as an extension of an already powerful corporate culture, and argued that green products just make companies richer, people poorer, and do nothing to slow the treadmill of human and ecological exploitation.[4]

|

Upper-class, liberal

|

Upper-class, conservative

|

|

Lower-class, liberal

|

Lower-class, conservative

|

Contention over the relative virtues of the ideal environmentalist is a cultural driver of polarization over the environment. Both liberals and conservatives are wary of accepting ways of caring about the environment beyond their own. And the ideal environmentalist has a great deal of cultural authority and respect, which conservatives perceive as being unearned and unfair. When I heard conservatives describe their frustration with the cultural power of the green consumer, I was reminded of an article written by two sociologists. In it, the authors wanted to know why people at the bottom of a status hierarchy assent to their inferior position. Their answer? When people lower in a hierarchy challenge those at the top, the group deems them unreasonable; people who don’t challenge the hierarchy are seen as reasonable and valued members of the group.[5] To put this in the context of polarization over the environment, when conservatives don’t accept the virtue of the ideal environmentalist, they are challenging a status hierarchy. While lower-class liberals assent to their status position, conservatives do not, setting off a series of judgements and reactions that prevent liberals and conservatives from accepting one another’s relationships with the environment.

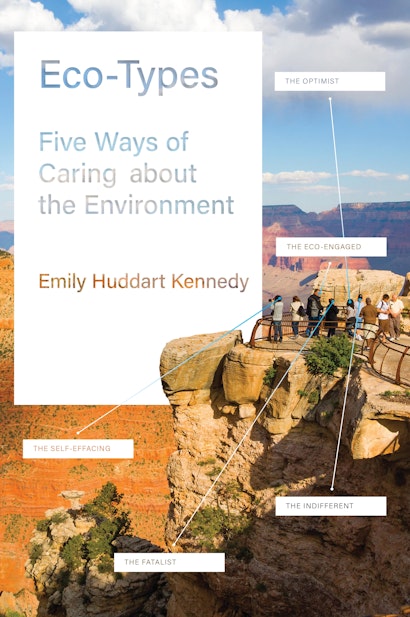

How else might someone care about the environment? Beyond those who reflect the ideal environmentalist, who I termed the Eco-Engaged, I identified four additional eco-types. The Self-Effacing worry a great deal about environmental issues, and although they want to take steps to reduce their personal footprint, they struggle to balance the competing priorities of managing their scarce finances and paying a premium for costly green goods. Interestingly, the Self-Effacing is the only eco-type that overestimates their carbon footprint. While the Eco-Engaged and the Self-Effacing care about a vulnerable planet, the next two eco-types care for a planet they see as powerful and resilient. The Optimists care about the environment by spending as much time as they can in nature. As one participant, Bill, told me: “It’s a longing, it’s a yearning. I need to be out and have that connection.” The Fatalists care about the environment by talking about how humanity has damaged it. They blame corporate greed and a complicit and powerless government for threatening ecological vitality, but they find comfort in their belief that once humans are extinct, the planet will rebound. In Ted’s words: the planet will “redo itself, cleanse itself, be fine” when we’re gone. Finally, there’s the Indifferent eco-type. The Indifferent watch environmental issues and tensions over the ideal environmentalist as interested bystanders. They aspire to integrate some of the ideal environmentalist’s practices—like gardening, cycling, and buying local foods—into their lives, but because they lack the know-how, the time, or the money, they can’t imagine how do get there from where they are now.

There are many ways of caring about the environment. I now try to approach unfamiliar environmental attitudes and practices with curiosity and empathy, by reminding myself that if I shared that person’s biography and social context, I would have the same relationship with the environment that they do. If buying an organic tomato can’t stop environmental catastrophes, battles over who cares more for the planet certainly won’t either. A better way to start is with acceptance of others’ relationships with the environment.

Emily Huddart Kennedy is associate professor of sociology at the University of British Columbia.

Notes

[1] Weng, Jude. “Chidi Sees the Time-Knife.” The Good Place. Netflix Canada, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2020.

[2] Kennedy, Emily H., and Parker Muzzerall. “Morality, Emotions, and the Ideal Environmentalist: Toward A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Political Polarization.” American Behavioral Scientist 66, no. 9 (2022): 1263-1285.

[3] See Kennedy, Emily Huddart, and Christine Horne. “Accidental environmentalist or ethical elite? The moral dimensions of environmental impact.” Poetics 82 (2020): 101448.

[4] In this way, lower-class conservatives diagnosed green consumption much like environmental sociologist Allan Schnaiberg theorized the relationship between the economy, labor and the environment. See Schnaiberg, The Environment: From Surplus to Scarcity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

[5] Ridgeway, Cecilia L., and Sandra Nakagawa. “Is deference the price of being seen as reasonable? How status hierarchies incentivize acceptance of low status.” Social Psychology Quarterly 80, no. 2 (2017): 132-152.