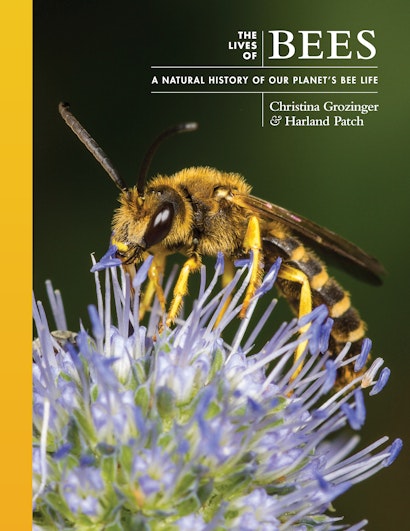

The Lives of Bees provides a one-of-a-kind look at the life and natural history of bees. Blending stunning photographs and illustrations with illuminating profiles of selected species, this incisive guide takes readers inside the world of these marvelous insects, exploring their physiology, behavior, ecology, evolution, and much more.

Why should people care about bees?

HP: Both of us originally became fascinated with bees because of their complex social lives and behaviors. They are really wonderful model animals to study to understand how and why animals (including humans) perform certain social behaviors, and how these behaviors evolved. One of these social behaviors is that they collect nectar and pollen and bring it back to their nest to feed their offspring. While collecting nectar and pollen from flowers, they transfer pollen between flowers, and this pollination service is what allows flowers to produce seeds and make fruit. This means bees are at the base of ecological food webs and essential for production of our fruit, vegetable, and nut crops and for feed (such as alfalfa) for our livestock. Honeybees and stingless bees also produce honey, and humans have a long history and culture of honey hunting and honey production. So, bees have it all: fascinating behavior, vital ecological and agricultural contributions, and deep cultural significance.

I would have never expected to see a chapter title like, “Building a home” or “Living with your sisters” in a book about insects. Can you explain how you chose these topics?

CG: We wanted our readers to understand how bees live in and experience the world. So, we structured the book around the major stages of a bees’ life, and what the bees were doing during these stages. Unlike the vast majority of insect species, bees create nests. Bees’ nests or “homes” can come in many different styles—in some species, bees will create their nests by digging out tunnels in the soil or in wood, while other species find an existing cavity and create compartments using leaves, mud, or wax. Bees collect food that they bring back to the nest to feed their offspring. In some cases, they collect the food—usually pollen and nectar—and place the egg on top of the food provision, and the larva feeds itself after it hatches. In other species, the adult female will continuously collect food and provide it to the growing larvae. Female bees can adjust how much and what kind of food they feed their larvae—which we discuss in the “Egg to adult” chapter. Foraging for food is a complex process which requires sophisticated sensory systems, learning, memory, and flower handling behaviors, which we describe in the chapter, “Finding food in a complex world”. Bees also have a variety of lifestyles. Most species are solitary, where a single, hard-working mother bee will create the nest, collect the food, and defend the nest. In some species, however, bees live in social groups with their sisters, and the sisters divide up the tasks among themselves, where some bees will lay most of the eggs and others build and defend the nest and collect the food. And of course, the world of bees is filled with cheaters and robbers, which we describe in each chapter. For example, some bee species have evolved to lay their eggs in the nests of other bees, parasitizing them in the same way a cuckoo bird parasitizes the nests of other bees, while other bee species collect their food by robbing the nests of other bees.

You have profiles of many different bee species in this book. Which one was your favorite?

HP: Bees are interesting for so many reasons. But they are unique among insects in having such a close relationship with humans through time and cultures. Domesticated silk moths are a close second. Of all the bees the Mayan stingless bee, Melipona beecheii, really captures my imagination. The biology of these bees is marvelous. They build their nests about a meter from the ground in hollow trees where there can be as many as 2,000 plus workers. All of course non reproductive females. Like honey bees they have a single queen. They make a honey that is quite thin, nectar-like, and spoils easily. I have been lucky enough to try this honey in the Yucatan region of Mexico. It tastes just like flowers smell. It also spoils easily so you have to try it on the spot. The ancient Maya developed a very sophisticated meliponiculture which was mostly to make an alcoholic drink called balche. If you ever visit Mayan ruins, particularly at Tulum, look for the upside down god Ah-Muzen-Cab. He is sometimes depicted as a person but also as a bee.

CG: It is hard to choose one! But I particularly like the Indian Alladopine Bee (Braunsapis kaliago). Females of this species invade the nest of a related bee species (Braunsapis mixta). They live in the nests with their host bees, and will sometimes ask for food from the host bees by patting the face of their hosts with their front legs. B. kaliago females have been seen to manipulate their eggs with their mouthparts, which seems to help the larvae hatch. They will regurgitate food to feed their larvae, and the larvae appear to beg for food from the adult females by curling their bodies towards them and making chewing motions with their mouthparts. The name of this bee species was derived from the Hindu goddess of death and destruction Kali—after all, this is a parasite that eats the eggs of its host.

You have each been studying bees for more than two decades now. Did you learn anything surprising when you were writing this book?

HP: This book gave me an excuse to spend time with the excellent and often adventurous natural history research of colleagues I have long admired. When you look at the detailed nest architecture of bees it is amazing how much variety there is and how adaptation has shaped this architecture. There is an oil collecting bee in central and South America called Epicaris zonata that makes a chamber nest in the ground and triple lines it with floral oils, resin and silt. Once the nest is provisioned and eggs are laid resin plugs are placed that create a waterproof chamber. During the wet season the landscape is under water but the developing brood is protected and emerges during the dry season.

CG: Most of my research has focused on the bees that are managed by humans for honey production and pollination, such as honey bees, bumble bees, orchard bees and leafcutting bees. So, it was a real treat to dig into the natural history of bees that have very different lifestyles or strategies. For example, the “vulture bees” are a group of stingless bee species that have evolved to collect carrion as food instead of nectar and pollen, though they process the meat they collect to a honey-like substance in the nest. Also, while I knew that bees were very good at caring for their offspring—or the offspring of their mother or sister in the case of social bees—comparing across different bee species shows how very carefully they manage brood production. For example, the Seven-spined Woolcarder bee needs to collect much more pollen for male larvae than female larvae, since the male larvae eat more and grow larger. So, the mother bee produces males first, and then, as the hairs that she used for pollen collection begin to fray and she cannot collect as much pollen, she switches to produce females.

The last chapter is titled, ‘Humans in a World of Bees”. Why this title, and not “Bees in a World of Humans”?

HP: Humans tend to think highly of themselves, but it is the little things that run our planet. We evolved from (mostly) fruit eating ancestors in our ape and primate lineage. And that fruit with all its micronutrients was made by (mostly) flowering plants, mostly pollinated by bees. The diversity of terrestrial life around us is partly the result of plant-pollinator communities. We live inside this world and are products of it.

What can we do to help the bees?

CG: First, go out into your backyards, botanical gardens, parks and natural areas and look around you to see what bees are there! Bees can thrive in all kinds of habitats, but we mostly do not notice them, or do not recognize that they are bees because we are only familiar with honeybees or bumble bees. There are more than 20,000 bee species in the world, and they come in all sorts of shapes, sizes, and colors.

Second, since the majority of bee species (except for those vulture bees!) rely on flowers for their food, and different bees prefer different flowers, it is important to create habitat that has a wide variety of flowering plants that can bloom throughout the growing season. Flowering trees and shrubs can be particularly important food sources for bees, since they produce so many flowers.

Third, bees make their nests in a variety of different locations and using different materials. About 70% of bee species nest in the ground, and so they need access to soil that they can dig in, while the others live in the pithy stems of plants, or in tunnels they excavate in dead wood. So, having plants that can provide these nesting materials is essential. Some bee species even use snail shells for their nests, so be creative with the options you provide them.

Fourth, bees need to have access to water. In addition to drinking the water, mason bees use water to soften the mud they use to construct their nests, while other species use it to cool their nests through evaporative cooling.

Fifth, reduce pesticide use. Insecticides are important for controlling pest insects, herbicides can reduce weeds or noxious species, and fungicides can prevent the spread of diseases. However, insecticides and fungicides can be toxic to bees, and many bees forage on flowers from weed species. Use an “integrated pest management” strategy, where you monitor for pests, weeds and diseases and only treat when it is necessary, and then use a variety of control and management strategies. If you must use pesticides, select pesticides that are less harmful for bees and do not last long in the environment, and apply them during periods when bees are not foraging.

We hope this book will give our readers a new appreciation of the beautiful diversity and complex lives of bees and inspire all of us to take steps to create habitat that can support bees and other wildlife in our backyards, cities, farms, and parks.

Christina Grozinger is the Publius Vergilius Maro Professor of Entomology and Director of the Center for Pollinator Research at the Pennsylvania State University.

Harland Patch is Assistant Research Professor in the Department of Entomology and Director of Pollinator Programming at the Arboretum at the Pennsylvania State University.