The bleakest time in modern bookselling history was May of 1993. As booksellers gathered for the 93rd Annual American Booksellers Association convention in Miami, a palpable, deep anxiety surrounded the event, as thick as the humidity outside. A tropical depression rolled in, turning the scattered rain into an unrelenting downpour. Upon arrival, booksellers greeted a city on edge. Years earlier, only a few blocks from the convention hotel, a Miami police officer shot two Black men during a traffic stop. Riots rocked the city in the immediate aftermath, and the threat of further rioting was rumbling in the background as the city waited for the appeals court to hand down a verdict in the officer’s retrial.

The overcast mood was heightened by the possible future the booksellers were facing. Chuck Robinson, then ABA President and owner of Bellingham Books in Washington, attempted to mitigate the dour vibe: “I don’t think it’s gloom as much as it’s anxiety. There is some anxiety over safety, but there is even more concern over the future of bookselling with the growth of mega-stores and now electronic publishing (publishers were releasing books on disks to be read on your PC). Selling books is like farming; what’s being threatened is not just a job, but a life. So any time there is a major change in retailing, everyone gets anxious.”[1]

Anxiety erupted into revolt at the annual membership meeting. Booksellers accused the ABA leadership of ignoring the looming threat of the chains. Several well-known and highly esteemed bookstores were going out of business after a superstore moved into their neighborhoods, including Chicago’s Krochs & Brentano’s, Albuquerque’s Salt of the Earth Books, and Shakespeare & Company of New York’s Upper West Side. Booksellers had been engaging in sporadic skirmishes for years over publishers’ unequal business practices with the chains. Demanding action, booksellers proposed and overwhelmingly passed two motions. First, the ABA was to investigate and document any and all unfair sales practices that threatened independent bookstores. Second, the ABA was to launch a nationwide PR and marketing campaign to educate the public on the importance and necessity of independent bookstores in preserving First Amendment rights. This opening salvo was heard ‘round the entire bookselling and publishing world.

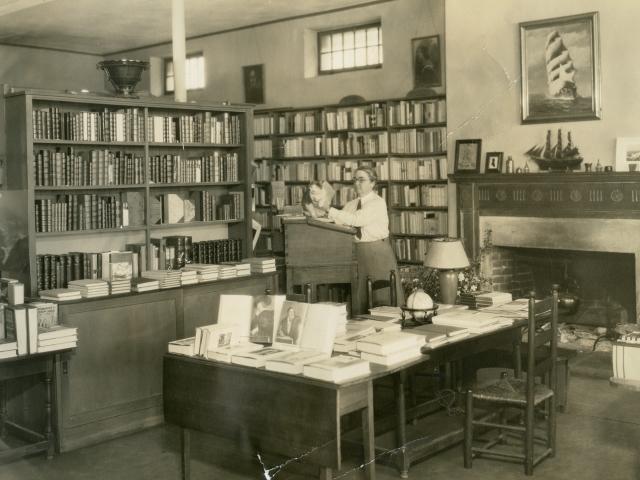

Flashback to seventy-seven years ago—a renaissance was blooming in bookselling. Two Smith College Alumnae, Marion Dodd and Mary Byers Smith, founded a bookstore in Northampton, MA. At a time when the only professions open to women were secretary, nurse, teacher, or librarian, the partners (in business and possibly at home) declared The Hampshire Bookshop to be the first “personal” woman-owned bookshop (it wasn’t). The women were original in other ways. They publicly issued a declaration of their purpose in opening a bookstore:

- To give all people the variety of pleasures that association with good books always provides: to make itself an indispensable aid to scholarship and research, thereby filling in the gaps of a college curriculum; to increase the reading habit by providing students with a selection of books which will develop a catholic taste in literature; to encourage the collecting of fine books as a means of developing sound criticism and discriminating judgment.

- To offer students the opportunity to save money by establishing a cooperative department somewhat similar to the plan in operation at Yale or Harvard which paid a certain percentage on student purchases at the end of the year in proportion to the profits of the business.

- To prove the aptitude of women for the book business.

- To demonstrate the fact that a college bookstore can sell all kinds of good books instead of merely textbooks and stationery, and possibly doughnuts.

- To make contacts between the author and his public.

This was a mission statement, not a business plan. Instead of ‘profits,’ ‘growth,’ and ‘cash flow,’ we have pleasure, cooperation, community, and connection. It was an entirely new approach to bookselling, which previously had been no different for customers than shopping at a general store. The women intentionally created a personal space that connected their community through the books.

By the end of the 1920s, hundreds of women had opened “personal bookshops.” As book historian Barbara Brannon pointed out: “The full participation of women in the industry decidedly transformed the book business, and the space of the bookstore, irreversibly toward the intimate and inclusive, fixing the bookstore in the American mind as a nexus of conversation, culture, and connection for decades to come.”[2] The Hampshire Bookshop did exactly that for the next fifty-five years.

In 1933, Marion Dodd formed an organization called the Bookshop Round Table. Dodd had been collaborating for years with three other women booksellers. She and her friends felt a larger alliance could work together to solve problems and work more closely with publishers. On February 10th, the proprietrix of nineteen personal bookshops met at the Women’s University Club in New York. One of the first initiatives was to collectively publish a bulletin for the customers of the group of shops which would both convey the attitude and values of their personal spaces and advertise a carefully selected list of books nominated by all the women.

The Bookshop Round Table met for about ten years, holding their meetings during the American Booksellers Association annual convention. Some of the topics they discussed were, “the problem of book clubs (meaning direct mail-order); what attitude to assume towards the National Book Awards of the ABA; new ways of creating interest in staple stock (now called backlist); new ways of capturing the attention and trade of the community; new books worth promoting.”[3] The group prioritized education and training for women in the book business. The values of the personal bookstore were applied to the bookselling community, changing competitors into colleagues. Their collaboration resulted in practices booksellers take as a given today. They convinced publishers of the necessity of issuing advanced copies of forthcoming books, and they redesigned the interior spaces of their stores to be more informal and intimate. This ‘personal’ identity spread across the country like the ivy on the brick exterior of a small town bookshop.

Booksellers have referred to themselves as “independent” as early as the turn of the century. Until the 1970s, “personal” and “independent” were used interchangeably to mean a small proprietor-owned bookshop. The adjective alluded to both the personal connections booksellers made with their customers and the personal, unique nature of the bookstore space. Beginning in the 1970s, this identity changed as stores needed to find ways to differentiate themselves from the emergence of modern chain bookstores. “Independent Bookstore” took on more meaning, signifying the bookstore was not just locally based but devoted to purpose over profit, free from the demands of stockholders, and dedicated to the importance of the book in our culture. In 1993, the major regional associations voted to include “Independent” in their names. They changed their bylaws to exclude members who did not have headquarters in the region. Booksellers had declared their independence.

By the 1994 ABA Convention in Los Angeles, the clouds showed signs of retreating. In contrast to the lean attendance in the previous year, a record number of booksellers showed up. After the May 27th announcement that the ABA was suing five publishers for alleged antitrust activities, booksellers were cautiously hopeful. Sociologist Laura Miller witnessed the drastic change in mood, “Booksellers were clearly buoyed by the sense that they had done something very daring in defense of their rights, and this was also for the greater good of book culture.”[4] The ABA also announced a new project—the creation of a National Independent Bookstore Week in November. Bernie Rath, the executive director, stated the focus was to help “readers understand the difference between booksellers and sellers of books.”[5]

National Independent Booksellers Week, with the coordination and support of the ABA, ran from 1994 to 1997. Using slogans like “Celebrating Your Independent” and “Building Community Foundations,” the messaging centered around the bookstores’ essential role in their communities. Militance gave way to marketing as other promotions, like “National Black Bookstore Week” and “National Feminist Bookstore Week,” followed. In 1999, the ABA consolidated these initiatives into a new national campaign called Book Sense. The Book Sense program raised consumer awareness and characterized independent stores as having knowledge, passion, character, community, and personality. The goal was to give independent bookstores a brand identity to rival that of the chains. Focusing on the theme of independence and the First Amendment, the bestseller list was “Book Sense 76”—a monthly list of 76 titles nominated by bookseller recommendations. Book Sense also attempted to help stores level the playing field with the chains by giving stores the opportunity to participate in a national gift certificate program and a Book Sense website.

A decade later, the buy-local movement was gaining traction after the release of two case studies—one which focused on Chicago’s Andersonville neighborhood with Women and Children First Bookstore participating. The Book Sense program began to feel antiquated, and parts of the program needed an overhaul. The ABA launched IndieBound in 2008. IndieBound shifted the message toward celebrating local bookshops’ positive impacts on their communities. Defined as a product of “ongoing collaborations between the independent bookstore members” of the ABA, the program is supported by most bookstores today.

On May 3, 2014, California booksellers held the first statewide California Bookstore Day with over 150 independent bookstores participating. The promotion, created by the Northern California Independent Booksellers Association, was a resounding success. Eager to replicate the event, booksellers across the country proposed the ABA implement a national Independent Bookstore Day. Citing daunting logistical issues and the complications of coordinating a hyperlocal project, the ABA declined. Undaunted, bookseller colleagues collaborated to launch their own grassroots campaigns. That July, nine independent bookstores around Chicago celebrated “Chicago Independent Bookstore Day” with book giveaways, raffles, treats, and discounts. BookPeople in Austin, Texas, picked a random August day to celebrate their own Bookstore Day. Soon the regional associations began working together, and the first national Independent Bookstore Day premiered in May 2015.

Unlike previous promotions, Independent Bookstore Day did not heavily push a particular message or agenda other than the day was to be a celebration of the independent bookstore. In 2022, 749 stores across 50 states participated, each in its own unique way. Hundreds of new stores have opened in the past few years, including many by a diverse group of young people. Veteran booksellers are cautiously whispering the words “bookstore renaissance.” That slim ray of light that brought hope to booksellers back in 1994 is now sparkling like a disco ball in a room full of elated dancers. The past thirty years have been challenging, even daunting. Booksellers have fought and cried, given up, and started over. They have mourned the bookstore casualties and encouraged others to join the cause. They have dedicated their lives to the amorphous ideal that is bookselling. While there are many miles to go, booksellers deserve a day of celebration; a day to show the world the good they have done and the power a community bookstore can have. Because, as Marion Dodd understood… the selling of books has always been personal.

Lanora Jennings has been a bookseller for 30 years. She is the Midwest Sales Representative for Princeton and Yale University Presses. She is also working on a book about the history of independent bookstores in America.

Notes

[1] Clary, Mike. “Gloom, Doom and Jittery Booksellers.” The Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1993. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-06-02-vw-42454-story.html.

[2] Brannon, Barbara A. “’We Have Come to Stay’: The Hampshire Bookshop and the Twentieth-Century ‘Personal Bookshop’.” Essay. In Rise of the Modernist Bookshop: Books and the Commerce of Culture in the Twentieth Century, edited by Huw Osborne, 25. New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

[3] Melcher, Frederic, and R.R. Bowker, eds. “Events Around the Convention” The Publisher’s Weekly 135, no. 18, May 6, 1939. archive.publishersweekly.com.

[4] Miller, Laura J. “Chapter Seven: The Revolt of the Retailers.” Essay. In Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption, 179. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

[5] Mutter, John. “Show Time in Los Angeles,” The Publisher’s Weekly 241, no. 25, June 20, 1994.