Women, as Virginia Woolf recognized, need rooms of their own to write. So, too, have women writers throughout history needed a term to describe what it is they do. In How Women Became Poets, Emily Hauser rewrites the story of ancient Greek literature as one of gender—redefining the canon as a constant struggle for women to be heard through, and sometimes despite, gender. She follows ancient Greek poets, philosophers, and historians as they developed and debated the vocabulary for authorship on the battleground of gender—and reinserts women into the traditionally all-male canon of Greek literature, arguing for the centrality of their role in shaping ideas around what it means to be an author.

Why is it important to reclaim the voices of female poets?

EH: Sappho was one of the most important poets (not just female poets: poets) in antiquity: her literary status surpassed that of most men. Yet Sappho was by no means the norm for a woman in ancient Greece. Most women lacked the same kind of access to education that their male peers had; those women who did become poets struggled to make their voices heard; and the subsequent erasure of their work by the male-ringfenced tradition that handed down ancient literature, that curated “the Classics” and said what should and shouldn’t be read, marginalized women’s writing even more. By delving into the surviving fragments of women’s poetry from the ancient world, and looking at what women were saying, in their own words, about what it meant to them to be a poet, I’m attempting not only to give the female poets a voice again, but also to demonstrate that they were actually central participants in the ancient Greek conversation around what it meant to be “a poet”. Although men ended up being seen as the prototypical poets, because authorship (in the West, looking back to classically-inspired models) was for hundreds of years the province of men, the early years represented a fiercely contested battleground of gender. In other words: it didn’t have to be this way.

I know you’re a writer yourself: did your experience of writing as a woman speak to how you looked back to poets like Sappho?

EH: All my writing—both my fiction and non-fiction—focuses on reclaiming the voices of the women of the ancient world. So the positionality of my experience as a woman writer in the present is inevitably on my mind. I actually had the idea for the book during a seminar I was attending at Oxford on Sappho in 2014—right around the time I was finishing my first novel, For the Most Beautiful, rewriting the women of Homer’s Iliad—and I came away thinking: what would Sappho have called herself? I knew Homer had a word to talk about his identity as a bard—aoidos, or “male singer”. But did she have any words, any space, to acknowledge what she did? This reflection on Sappho’s context and her role in history intersected with my journey as a woman and a writer, and sparked my contemplation on issues of gender and identity, all the way back to antiquity.

So is this just a story about Sappho?

EH: Absolutely not: although Sappho was the starting point, I quickly realised, as I came to write the book, that it’s not possible to talk about women in ancient literature without thinking about the category of gender more broadly. This includes the kinds of dichotomies that get set up, particularly in male-authored poetry, the way men work hard to construct the ‘masculinity’ of authorship and reinforce the binary opposition of gender (words are for men, not for women—a near-perfect quote of a brush-off that Telemachus gives to his mother Penelope near the opening of Homer’s Odyssey). One of the biggest revelations of the book, for me, was that this is a much bigger story about how we tell the story of gender in words: we can’t extract gendered identities from the way we speak, perform and write, and the way that traditional scholarship talks about “the poet” elides the fraught and high-stakes battle that continually unfolded to shape the gendering of literature. So we witness men constructing the edifice of the “male poet” and working to make it appear inevitable; playwrights playing around with the gender binary and modelling what a nonbinary poet might look like; as well as women attempting to make their voices heard by using a new language to express their identity.

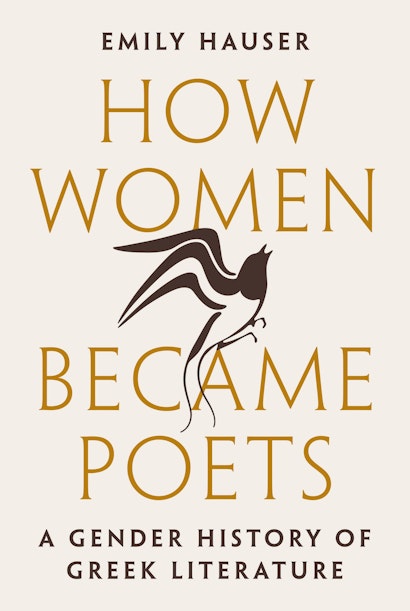

Can you explain the image of the bird on the book’s cover?

EH: It comes from a gorgeous wall painting from an ancient Bronze Age town at Akrotiri, Santorini. The buildings were buried under the eruption of Santorini’s volcano around 1600 BCE. The painting—incredibly well-preserved under the thick layer of volcanic ash—shows a lush scene of a mountain landscape in spring: blue and red crags sprouting lilies, with swallows spiralling above. The bird motif recurs throughout the book, as a representation of how men try to pigeonhole women’s writing and silence their voices (I’m thinking particularly of the legend of Philomela, who was raped by her sister’s husband, had her tongue cut out to stop her speaking, and was turned by the gods into a swallow or, in some accounts, a nightingale). But it’s also an emblem of how women reclaim that image and turn it into a new word to describe their own song: the nightingale is a well-known songbird, and the Greek word for nightingale, aēdōn, is a feminine noun that translates literally as “female singer”—a clever analogy for a woman poet. The book’s cover, with the bird flying free out of the words that describe her, captures this beautifully.

What do we find when we read ‘women’ into histories that often exclude them?

EH: We get a better, more accurate, more informed picture of history. If we keep telling a male-oriented history of Greek literature, we’ll be fostering a story about the ancient world that fails to represent the voices of all the women who sought to be heard. The legacies of that past, and those strategies of gender marginalization, are still palpable today. Writing more inclusive histories of ancient literature (and that means all kinds of inclusivity, whether that’s along the lines of race, gender, class, or sexuality) means we can interrogate the past and foreground the voices that weren’t heard, in the hopes that they can be now.

Emily Hauser is Senior Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, and the author of the acclaimed Golden Apple trilogy retelling the stories of the women of Greek myth, including For the Most Beautiful (2016).