The topic of intellectual disability seems frequently to function as a conversation stopper, and establishing the full humanity of individuals with complex developmental impairments has been an ongoing struggle in every nation in the world, including the U.S. It has taken, and all too often continues to take, enormous dedication, stamina, and creativity to combat the wider public’s as well as politicians’ incomprehension and ambivalence about, if not full-fledged resentment at, the perceived costs in time, energy, and funds of quality therapeutic care, appropriate accommodations, and specialized education. A recent case that made U.S. news concerned Fred Trump III, nephew of former president Donald Trump, who has an adult son, William, with significant physical and intellectual disabilities whom he and his wife Lisa love dearly and whose presence in their life has made them into ardent disability rights activists. In a book previewed in Time in 2024, it was revealed that Donald Trump had, while in the presidency, frankly opined with regard to “those people”—adults with multiple and severe impairments—“the shape they’re in, all the expenses, maybe those kinds of people should just die.” To Fred Trump’s horror, moreover, he subsequently included also William explicitly in that recommendation.

People with disabilities were the first victims of Nazi genocide, and the initial phase of the “euthanasia” murders literally served as template for a substantial portion of the Holocaust. Ultimately more than 210,000 fellow citizens with disabilities were killed, along with another 80,000 in Nazi-occupied Poland and the Soviet Union. Yet not until the 1980s would these murders, as well as the coercive sterilizations of some 400,000 others, the majority classed as “feeble-minded,” be officially acknowledged as crimes at all—not least because the humanity of the victims remained in question. Nor is it irrelevant that the U.S. in the 1930s had explicitly denied visas to individuals with intellectual and physical impairments (the law would not change until 1990)—and thus also Jewish families fleeing the Third Reich were forced to leave disabled family members behind.

While there is a growing body of scholarship which stresses the broad international prestige of eugenics in the first decades of the twentieth century—in fact, the U.S. was very much in the lead in promoting the scientifically false premise that intellectual deficiency was hereditarily transmitted—the German case, precisely in the specifics of its prehistory and in its extremity, can teach us a great deal that remains relevant today. For the notion that the best way to solve a care crisis is by systematically eliminating those most needful of care has obviously not vanished from our cultural imagination.

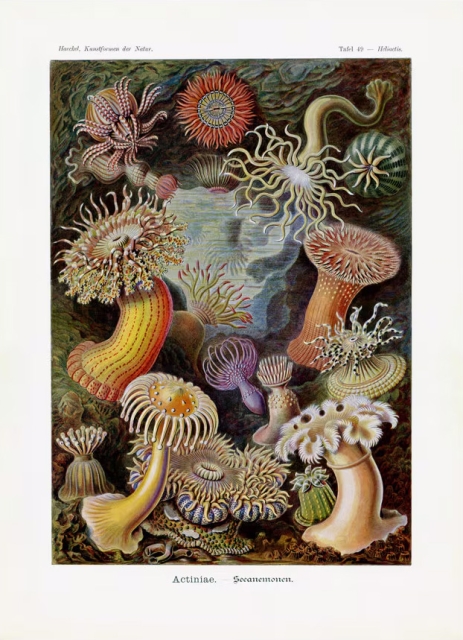

Germany had been precocious in its provisioning of residential institutions for people with significant impairments and in the development of remedial schooling, but already around 1900 it was becoming socially acceptable to express death wishes towards people with intellectual impairments—and particularly the directors of the Protestant charities that provided the bulk of daily care found themselves on the defensive. Diverse rationales were taking shape. One was pity, best captured in the oft-cited aphorisms of Friedrich Nietzsche, who had written of a disabled infant that it would be “more cruel” to let it live than to kill it. A second was based in cost-benefit utilitarianism. Yet no conceptual touchstone would be more compelling to more people than the dream of racial perfectibility advanced by zoologist Ernst Haeckel (best known to us for his drawings of sea anemones, so gorgeous they inspired art nouveau) who recurrently revived the story, once told by Plutarch, of the ancient Spartans said to have left their frail or deformed children to die on Mount Taygetos. And it was Alfred Ploetz, biologist and promoter of a “racial-hygienic utopia,” who in 1895 amplified the significance of the soon ubiquitously invoked Spartans not only by dwelling in vivid detail on their infanticidal ways, but also by presenting them as transgressively inspirational in their sexual customs, as pre- and extramarital intercourse were not just permitted but celebrated when these were believed likely to produce healthy—and also, expressly, intelligent—offspring. (Ploetz’s vision would become Nazi policy.) The innovation here was to connect conceptually the ancient practice of infanticide with the aspirational ideal that the Germanic people would become—by continually killing off the deformed and weak—strong and beautiful and smart. Lethal malice and the promises of pleasure and superiority were becoming affectively sutured.

Meanwhile, although physicians all along had known full well that the main causes of mental disability lay in poverty, inadequate nutrition, and the untreatable brain fevers and infections of toddlerhood in this era before antibiotics, more and more commentators began to reverse causation, blaming the poor for their misfortunes and asserting emphatically that impairments must be hereditarily transmitted. Already before World War I, a statistical controversy erupted, concretizing the notion that repulsive infirmity within the nation was both enormous and real, as experts debated what percentage of the German populace should be considered “permanently unsuitable for the production of offspring.”

And then Germany lost the war. The wound to national pride was immense, and the ensuing diffusion of a eugenic worldview—both histrionic assessments of the size of the problem and insistent propagation of the fiction that cognitive deficit was hereditary—can best be understood as a corollary to the more notorious Dolchstoßlegende, the (antisemitic) stab-in-the-back myth that, instead of acknowledging that the Imperial German Army had been trounced on the battlefield, blamed the defeat on the machinations and betrayals of Social Democrats and Jews on the home front. But no less consequential was the participation of Christian care-providers in appropriating eugenic language for agendas of their own.

A new national conversation took shape largely in reaction to one slim book published in 1920, Permission to Annihilate Life Unworthy of Life, coauthored by lawyer Karl Binding and psychiatrist Alfred Hoche. Their provocation shifted the terms dramatically, as they proffered a concrete proposal for how those individuals they called “incurable idiots” were to be selected—this “life unworthy of life” (their indelible coinage), “ballast-existences” lacking in all “affection-value.” But rather than retort that also disabled life was cherishable, Protestants preferred to theorize that the presumptively rising numbers of cognitively disabled Germans were the result of a surfeit of sexual sin in Weimar’s licentious culture, encouraged not least by the “media-Jews.” And while they rejected murder, they came to settle on the compromise of approving sterilizations. Exacerbating stigma by concurring their residents were repellent, their case for keeping the disabled alive was that doing so should provide a valuable lesson in chastity for the nondisabled. When the Third Reich arrived, they welcomed it in fulsome terms. And once the Nazis’ coercive sterilization law of July 1933 went into effect, while Catholics registered vigorous objections—though eventually they accommodated the surgeries as well—Protestants sterilized with avid enthusiasm.

Christians’ enmeshment in this particular Nazi mass crime would come to be a key factor—long unacknowledged but signally pertinent—in the aggressive refusal of recognition faced by traumatized survivors and kin of the murdered in the postwar. It was to take decades before audacious radicals in both East and West initiated a comprehensive moral revolution in thinking about disability and developed a panoply of extraordinary counter-projects. It is thanks, too, to these radicals that both Nazi “euthanasia” and the coercive sterilizations have come to be formally acknowledged as grotesque crimes whose pursuit had been based in both cynical opportunism and phantasmatic delusions. And it is to the credit of their tenacious activism as well that when present-day politicians attempt to reintroduce crass antidisability messaging—as, for instance, members of the far-right AfD obsessively do—the derogatory propositions are met with emphatic critical rebuke. From secular rights advocates and from both Christian churches.

Dagmar Herzog is Distinguished Professor of History and the Daniel Rose Faculty Scholar at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Her many books include Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability in Post-Nazi Europe and Sex after Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany (Princeton).