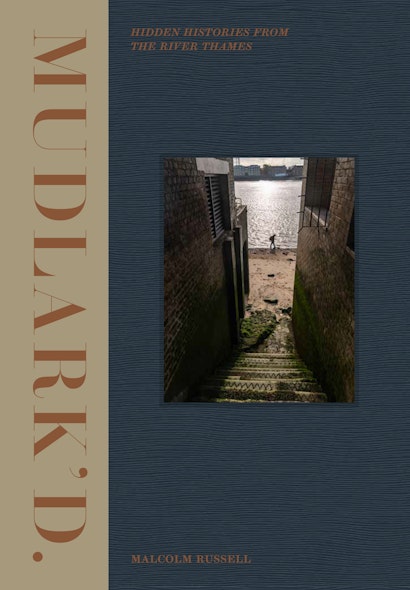

For millennia, objects have found their way into the River Thames as it flows through London. Household rubbish has been dumped into it, personal possessions accidentally lost, cargoes spilt, offerings made to gods, and coins tossed in for luck. This ‘mud archive’ of the capital’s past might have been lost forever, except the Thames, as it flows through London, is tidal. This means twice per day part of the riverbed is exposed: the Thames’ foreshore. I’ve spent the past six years descending precarious ladders and hidden steps to search this area, an activity known as ‘mudlarking’. I’ve found many thousands of objects from Roman gaming counters, Tudor rings, eighteenth century wig curlers and contemporary spells. These have been discovered not by using a metal detector or digging, but simply by scouring the surface by eye for items the Thames’ currents have eroded from the thick, black mud.

These objects are mostly the stuff of ordinary people: London’s workers, drinkers, smokers and entertainers. Its sailors, immigrants, criminals and housewives. Its poor and its marginalized. Most finds are worth nothing monetarily, but each one offers up an invaluable little portal into past lives. And so, the idea behind Mudlark’d was to use objects found in the Thames to explore the lives of centuries of everyday Londoners. I think of it as a people’s history.

While looking among the sludge and shingle early one morning, I plucked an eighteenth-century bone die from between two rocks. This led me to Georgian London’s prodigious gamblers, in particular players of ‘Hazard’. This game of chance saw large sums wagered on each role of the dice and led to ruin and even suicide for some players, helping prompt a moral panic in which excessive gambling was seen as the cause of many of Britain’s ills, including the loss of its American colonies. Another day’s find—a delicate Roman hairpin, preserved for two millennia in the mud—revealed the story of ‘ornatrices’: women hairdressers who were often enslaved. An eighteenth-century cufflink with an ostentatious glass jewel led me to the queer associations held by the fashionable ‘macaronis’ of the era. Each find helps brings such lives out of history’s shadows and into the light, adding a visceral reality to the past that can rarely be experienced when working with texts alone.

Mudlarking also introduces a serendipity to exploring the past—a starting point more akin to one of the compositional ‘Oblique Strategies’ used by David Bowie, than a conventional reading list, curriculum or excavation. Unlike a conventional archaeological site, there is often no stratification on the Thames foreshore; layers of the past lie undone and chaotically strewn together by the river’s waters. I’ve found a 10,000-year-old Mesolithic flint tool lying on top of a McDonald’s plastic straw, right next to a seventeenth century broken buckle. This means I never know what corner of the past I’m going to end up visiting, constantly challenging my ideas about where my historical interests lie and pushing the possibilities for research in new directions. For instance, while searching the foreshore early one autumn evening, I plucked the bowl of a clay tobacco pipe from a pool of water. Dating to around 1890–1910, it features a depiction of a parachutist on each side, surfacing the forgotten phenomenon of the turn-of-the-century stunt parachutist. Often young women, these performers would ascend in a hot air balloon before leaping out and floating back to earth precariously perched on a trapeze bar suspended beneath their parachute. They were enormously popular performers at fairs and carnivals, with many unfortunately meeting an untimely end, or ‘leaving the team’ as their fellow parachutists described it. Another time, a battered enamel badge featuring the letter ‘F’ and the inscription ‘For King and Country’ revealed to me Britain’s first avowedly fascist organisation—the British Fascists. It is often thought British inter-war fascism was the sole preserve of Oswald Moseley’s B.U.F. But the British Fascists pre-dated Moseley’s organisation by almost a decade, having been established by former ambulance driver with the Scottish Women’s Hospital Corps, Rotha Lintorn-Orman. Following the lead of its founder, women members played an especially active role. Perhaps the badge ended up being flung into the Thames as conflict with Nazism led to the internment of anyone suspected of fascist sympathies, or when the organisation fell apart following Lintorn-Orman’s death from alcoholism.

Other mudlarking finds reveal London’s connections with the world. The city was for centuries, not only England’s capital, but also its busiest port. In the eighteenth century it was said you could walk across the Thames by stepping from boat to boat moored at its docks. With the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement there have been calls for a better understanding of Britain’s slave-trading, colonial and imperial past. In its own modest way mudlarking can help, through highlighting the multitude of material scraps of these activities, hiding in plain sight right in the middle of London, waiting to be picked up by any member of the public with a mudlarking permit. I’ve recovered many colourful glass beads that helped facilitate the transatlantic slave trade, hundreds of tobacco pipes and fragments of eighteenth-century sugar refining materials, and cartridge cases from the ammunition used by the British Army to suppress resistance during the ‘Scramble for Africa’. I even found a turn-of-the-century Chinese-made opium pipe hailing from when popular fascination with East-End Chinese-run opium ‘dens’ blended with the psycho-cultural fear of the ‘Yellow Peril’ to populate pulp novels and press reports.

As well as a point of arrival and departure for goods, people and materials, the Thames has played a spiritual role in the lives of Londoners since the city’s founding, and before. Like other liminal zones, it has been a place for offerings. Many Bronze Age copper-alloy spear heads have been recovered from the river, seemingly ritually damaged before being placed in its waters. Another highly prized find among London’s mudlarks are medieval lead-alloy pilgrim badges. These were purchased by visitors to saint’s shrines, with England’s leading destination being Canterbury, the centre of the blood cult of brutally murdered archbishop, Thomas Becket. Such souvenirs were believed to carry with them some of the wonder-working properties of the shrine. It has been suggested many of those found in the Thames were cast into the river to give thanks for a safe homecoming.

Mudlarking is a highly democratic way of accessing the past. No special qualifications or expertise are required—only a permit from the Port of London Authority. One condition of this permit is that noteworthy finds should be recorded on Portable Antiquities Scheme database. This scheme—the largest of its kind worldwide—is designed to record small finds of archaeological interest made by members of the public. With over 10,000 objects found in London already recorded, it provides an invaluable resource from which we can all learn, and inspiration for others to try mudlarking and discover some more hidden histories.

Malcolm Russell has contributed to publications such as Treasure Hunting, The Searcher, and Beachcombing. A lifelong mudlark, he studied history at the University of Sheffield, where he was recently an honorary research fellow in the Department of History. His remarkable finds were featured in the Thames Festival exhibition Foragers of the Foreshore.