I grew up in a house on the campus of a boarding school in Connecticut. My father taught history and coached the wrestling team, while my mother taught art. Our lives were totally immersed in this insular academic world—the school was our home and our playground. I remember hearing the muffled sounds of the lessons and feeling the anticipation that classes were about to end, finally allowing us to go inside and play. The classrooms were often hot and musty and smelled of teenagers and chalk. This was my world—it was all I knew.

Many years later, I find myself back in dusty, chalk-filled classrooms. I am photographing the chalkboards of eminent mathematicians. How did I get here? The deeper answer, most likely, is that it still feels like home to me. The more immediate reason, however, comes out of a friendship in another part of New England.

Every summer, I take a break from academia, leaving my home in New York City to join my family in a small beach town on the outer tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Over the years, I’ve become very close to my neighbors, who live in a house once occupied by my paternal grandfather. Amie Wilkinson and Benson Farb are a married couple and parents of two. They are also theoretical mathematicians who teach at the University of Chicago. Amie’s research focuses on smooth dynamical systems and ergodic theory; Benson’s work explores low-dimensional topology and geometric group theory.

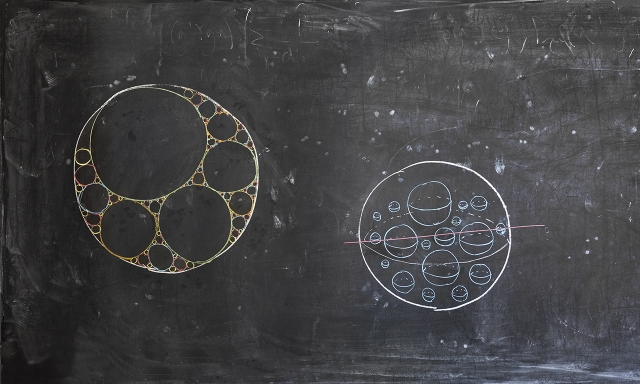

Amie and Benson are “theoretical” or “pure” mathematicians, which means they do “math for math’s sake.” They are interested in ideas, abstraction, exploring the boundaries of pure reason without explicit or immediate application in the physical world—akin to art, philosophy, poetry and music. Practitioners of applied math, on the other hand, use theories and techniques to solve “practical” problems in the physical world. Although their objectives are different, these two branches of mathematics are inextricably linked: there are numerous examples of discoveries in pure math that were abstract at the time but would be revealed to have revolutionary applications years later. In fact, one could say that all modern technology is derived from pure mathematics.

The chalkboard is one of the oldest and most important analog tools for learning. At first, students used small, individual pieces of slate, and would sit at their desks working on their boards. But their teachers had no way to share and demonstrate their work with an entire class. Although there is some dispute about the date, many say that the first large chalkboard was installed in a classroom in 1801. Eventually it evolved into what we know now: a large object, typically with a black or green surface, hanging on a wall. No longer made of slate, most boards are made out of porcelain enameled steel.

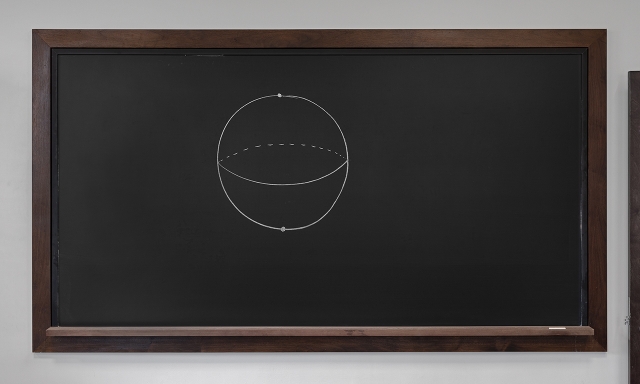

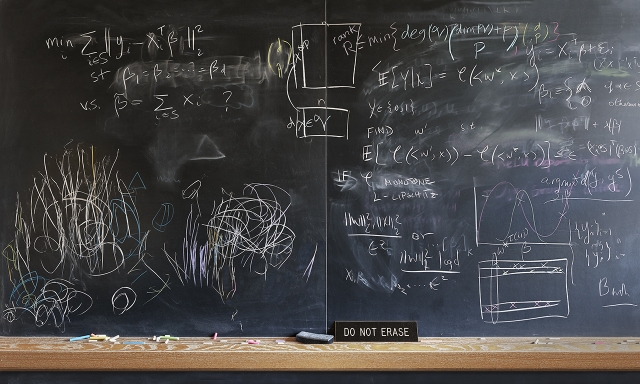

Despite technological advances (such as the creation of computers), chalk on a board is still how most mathematicians choose to work. As musicians fall in love with their instruments, mathematicians fall in love with their boards—the shape, the texture, the quality of the special Japanese Hagoromo chalk. The boards are their homes, their labs, their private thinking spaces.

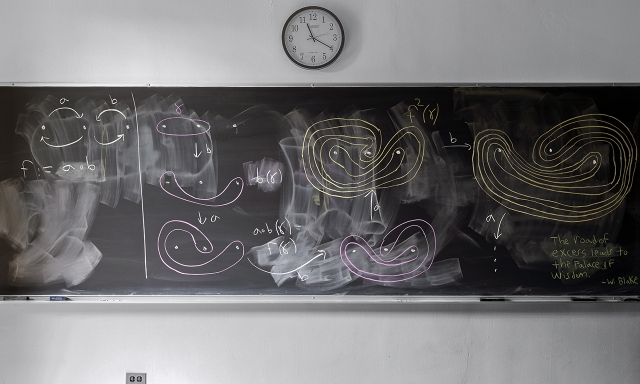

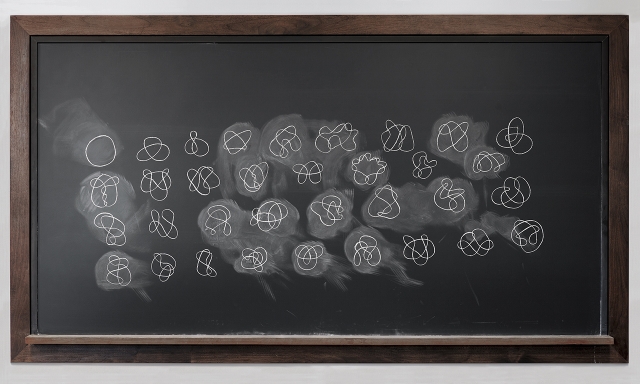

When a mathematician starts writing on an empty board, they often have no idea where they are going. The board leads them there, like a blank page for a writer, or an empty frame for a photographer.

Working on a chalkboard is a physical, time-based act. It lets the narrative of solving a problem unfold in real time, slowing thought down and allowing the information to be more easily absorbed. The speed of thought, observation and quiet contemplation doesn’t always match the accelerated velocity of digital technology—faster isn’t necessarily better when you’re creating and discovering. The tactile experience of holding chalk and drawing on a board influences the way one thinks. All of your senses are engaged, and your body is moving through space. Your brain is lit up. Thoughts are exploding—erupting—at the moment of discovery, like the big bang of creation.

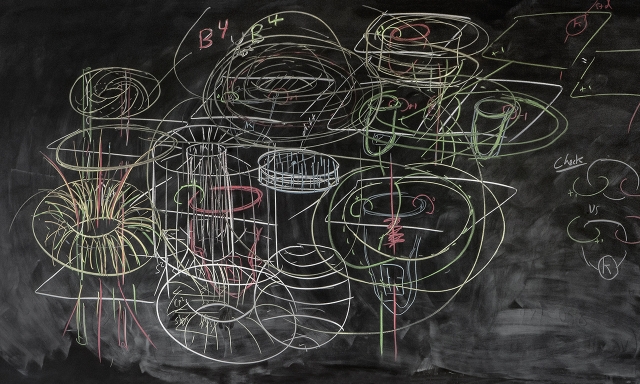

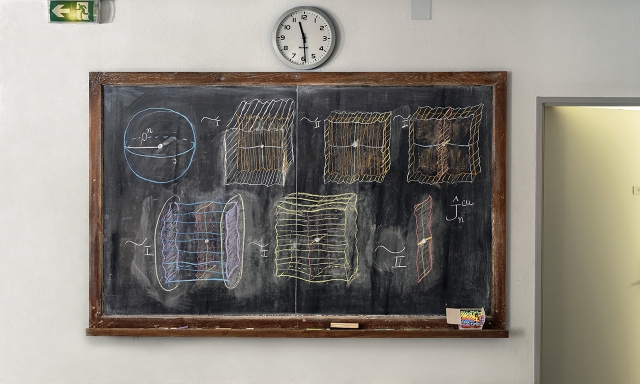

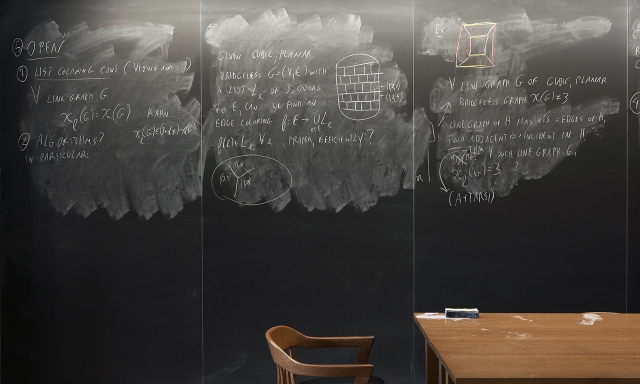

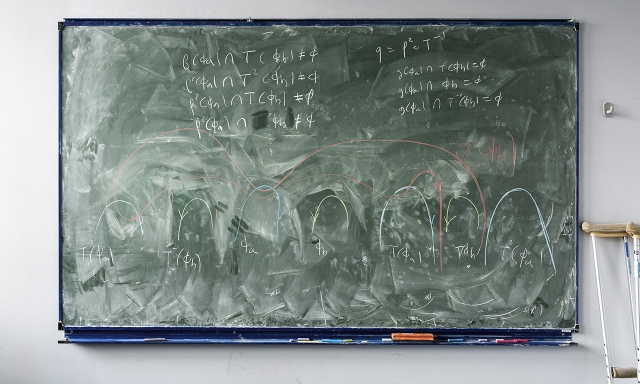

Before I start photographing the mathematicians’ chalkboards, I set a few parameters. I will only photograph actual chalkboards—no glass or white boards—mainly for their inherent beauty, but I also want no signifiers of time. I will ask each mathematician to write or draw whatever they want on their boards. (Sometimes, as it turns out, I end up shooting whatever is already on the board—something they are currently working on.) I will photograph in a literal, objective, straightforward way—showing the chalkboards as real objects—capturing their texture, erasure marks, layers of work, and all forms of light reflecting off their surfaces.

I begin in New York City, my home. The mathematicians at Columbia University and The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences (at New York University) are welcoming; I describe my project and they seem to immediately understand. They are intimately familiar with the beauty of math, and they want to share it with me.

The formulas and mathematical symbols are inaccessible to me. And I don’t mind not knowing. I actually like the tension of being seduced by the formal abstract beauty—the patterns, symmetry and structure—while simultaneously feeling totally disconnected, not being able to fully access the meaning of their work. This friction of being drawn in and pushed away is exciting to me. I may not know the specific meaning of the theorems, but I do know that beyond the surface they are ultimately revealing (or attempting to reveal) a universal truth.

The world of mathematics is a dynamic ecosystem, an intersecting web of influence and collaboration in a constant state of growth and flux. I photographed the chalkboards of mathematicians to show the mystery and beauty of mathematics, things that otherwise may be overlooked. The work of these great explorers should be preserved, honored and recognized: they are expanding knowledge—seeking the truth—and building upon what has come before.

I am fortunate because I was able to see, and now share, something that most of the world never gets to enjoy—the world of higher mathematics. It is a remote, austere world, and is, to some extent, a secret society. I am deeply thankful to the mathematical community for inviting me in and allowing me to record their work and bring back the evidence that there is mystery, insight, discovery, truth, and beauty all around us, hidden away in dusty, chalk-filled rooms around the world.

Jessica Wynne is associate professor of photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Her photographs are in collections at the Morgan Library & Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and have been exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, the Guardian, the New Yorker, and Fortune. Wynne is represented by Edwynn Houk Gallery and she lives in New York City. Twitter @jessicawynne6 Instagram @jessica___wynne Website www.jessicawynne.com