When was the last time you read a forbidden text? Not forbidden in some other time and place, but here and now, a text that, were it discovered in your possession, might land you in prison? The possibilities in today’s America (apart from certain public school libraries) are vanishingly small, mostly limited to the realms of child pornography, classified military and intelligence documents, and insider trading.

Forbidden texts were the lifeblood of the Soviet dissident movement. Collectively known as samizdat, a Russian neologism meaning “By Myself Publisher,” such texts were reproduced and disseminated by thousands of readers armed with nothing more than typewriters, carbon paper, and networks of trusted friends. Samizdat authors and readers thumbed their noses at the state monopoly on publishing and the accompanying system of censorship. The term samizdat itself parodied the Orwellian names of official Soviet publishing houses such as gosizdat (State Publisher) and politizdat (Political Publisher). Thanks to the Cold War, “samizdat” entered the pantheon of Russian words that had found their way into western languages, along with “tsar,” “vodka,” and “pogrom.”

By the 1960s, samizdat encompassed uncensored texts of every imaginable provenance and genre, whether official (but not meant for public circulation) or unofficial, foreign or Soviet, fictional or documentary. Its purveyors fed the Soviet intelligentsia’s insatiable textual appetite. Soviet citizens, as their government never tired of proclaiming, may have read more than any other people in the world. What is certain is that they typed and retyped more than any other people in the world. Every document reproduced and circulated via samizdat became a kind of chain letter addressed to an indeterminate, risk-sharing, infinitely expandable readership. As one enthusiastic reader put it (quoting the American scientist John Robinson Pierce), “From slaves of misinformation we shall become masters of information.”

The attraction of samizdat as an autonomous medium was so pervasive as to generate both alarm and humor. In a 1969 memorandum to the Communist Party Central Committee, KGB chairman Yuri Andropov reported his agency’s discovery of the “preparation and dissemination of ‘samizdat’ ” in Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, Odesa, Novosibirsk, Gorky, Riga, Minsk, Kharkiv, Sverdlovsk, Karaganda, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Obninsk, and other cities across the USSR’s eleven time zones. Shortwave radio broadcasts by the BBC, the Voice of America, and other western transmitters, Andropov warned, “are acquainting a significant number of Soviet citizens with the contents” of uncensored texts. One popular joke of the time featured a telephone conversation between two samizdat readers who assume the KGB is listening in:

“Did you finish the pie?”

“We’ll finish it up tonight.”

“When you’re done, pass it on to Volodia.”

In another, a woman brings Tolstoy’s War and Peace to a typist to copy. “What for?” exclaims the bewildered typist. “You can buy this in a bookstore.” “I know,” answers the woman, “but I want my son to read it.”

Samizdat provided not just new things to read, but new ways of experiencing the act of reading. There was binge reading: staying up all night pouring through a sheath of onion-skin papers because you’d been given twenty-four hours to consume a novel that Volodia was expecting the next day, and because, quite apart from Volodia’s expectations, you didn’t want that particular novel in your apartment for any longer than necessary. There was slow-motion reading: for the privilege of access to a samizdat text, you might be obliged to return not just the original but multiple copies to the lender. This meant reading while simultaneously pounding out a fresh version of the text on a typewriter, as a thick raft of onion-skin sheets alternating with carbon paper slowly wound its way around the platen, line by line, three, six, or as many as twelve deep. “Your shoulders would hurt like a lumberjack’s,” recalled one typist. There was group reading: for texts whose supply could not keep up with demand, friends would gather and form an assembly line around the kitchen table, passing each successive page from reader to reader, something impossible to do with a book. And there was site-specific reading: certain texts were simply too valuable, too fragile, or too dangerous to be lent out. To read Trotsky, you went to this person’s apartment; to read Orwell, to that person’s.

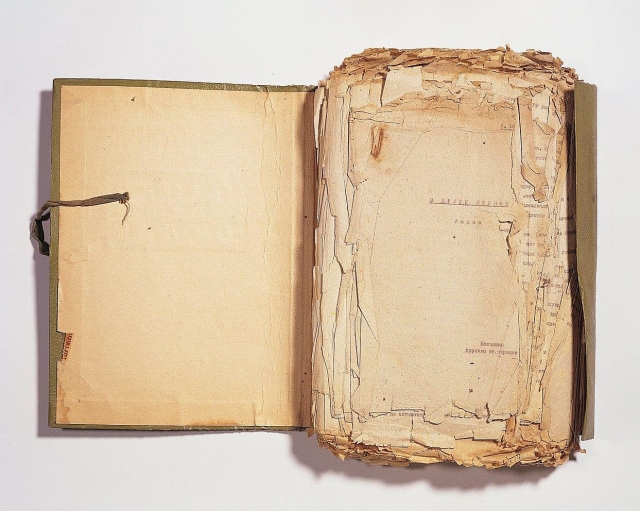

However and wherever it was read, samizdat delivered the added frisson of the forbidden. Its shabby appearance—frayed edges, wrinkles, ink smudges, and traces of human sweat—only accentuated its authenticity. Samizdat turned reading into an act of transgression. Having liberated themselves from the Aesopian language of writers who continued to struggle with internal and external censors, samizdat readers could imagine themselves belonging to the world’s edgiest and most secretive book club. Who were the other members, and who had held the very same onion-skin sheets that you were now holding? How many retypings separated you from the author? More than people coming out to protest on city streets and squares, what moved in the dissident movement were texts. Its central activity, the only one that achieved truly mass proportions, and the only one that required a new word to describe it, was samizdat.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991—an event facilitated by samizdat’s gradual erosion of the Kremlin’s tightly regulated economy of information—was soon followed by the emergence of the World Wide Web. Early Internet enthusiasts liked to describe it as high-tech samizdat, a radical, autonomous medium that would allow hundreds of millions of users around the globe to share uncensored information of every kind. This imagined free-speech utopia ignored the fact that the Internet, unlike samizdat, is ultimately controlled by a handful of profit-driven (and now staggeringly wealthy) companies. Unlike samizdat, a diffuse and ownerless technology, the Internet has also proven vulnerable to states bent on censorship and disinformation (see today’s Russia and China, among others). Like so much else about the post-Cold War world, Soviet dissidents’ “hopeless cause” awaits its full realization.

Benjamin Nathans is the author of Beyond the Pale: The Jewish Encounter with Late Imperial Russia, which was awarded the Koret Jewish Book Award, the Vucinich Book Prize, and the Lincoln Book Prize, and was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award in History. A frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books and the Times Literary Supplement, Nathans is the Alan Charles Kors Associate Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania.

Adapted from To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement by Benjamin Nathans.