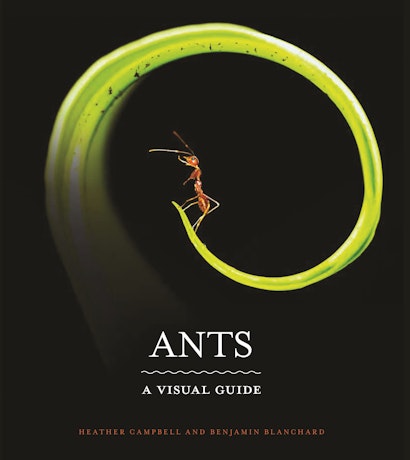

The temperature is climbing, and the great outdoors is teeming again with flowers, insects, birds, and creatures of all shapes and sizes. To celebrate the coming of summer, we asked several of our naturalist writers and scholars to respond to the following question: How did you fall in love with natural history? This week, we hear from Dr. Heather Campbell, an expert of insect ecology and author of Ants: A Visual Guide.

“Have you always loved insects?” This is one of the most common questions I’m asked, and the surprising answer is no!

I’m aware that a lack of childhood bug geekery sets me apart from many colleagues. Among my entomology peers, I frequently encounter “the taxon nerd,” an individual with a singular fiery passion for their six-legged obsession. They will wax lyrical about bejeweled insects with jaunty, colorful patterns that exist in benevolent harmony with humanity. And their enthusiasm is relatable. Other times the target of their affections is harder to grasp. They will love a peculiar carrion beetle whose life revolves around raising a family on decaying animal carcasses. Or they rave about pincer-endowed pseudoscorpions that amble away their miniscule lives otherwise unheard of in the leaf litter. Every weird insect group has its enthusiast—even the insects that are the pests of the kitchen, the scourge of crops, the stingers and biters and wholly unlovable creatures that put the creepy with the crawlies.

What often unites the taxon nerds are tales from their misspent youths of insect collecting. Their one true purpose dedicated to a life studying invertebrates. But for me it didn’t happen that way. I never laid awake at night pondering the symbolism of death’s head hawk moth markings or the acrobatic hunting fights between male emperor dragonflies. Rather my love of natural history developed more delicately. A slow burn, not a raging inferno.

I’ve always been happiest outside and close to nature. Even growing up in an era before home computers and smartphones it was a true escape to be outdoors. But I would never have been out collecting beetles in my mouth, as an oft-told anecdote about Charles Darwin describes.

My parents worked in a factory and supermarket, and when I went off to university, it was without any family insight of what I was heading into. I loved biology and enrolled in a pre-med course. Then during my first year, something wondrous happened. I took a module enigmatically titled the Diversity of Life. It was led by one of the most knowledgeable and fervent natural historians I’ve encountered and spanned every organism imaginable, from bacteria through to fungi, plants, and animals. It was wonderful. And that was when the spark was lit. Never in my working-class upbringing had I considered that studying the natural world was a serious pursuit. Perhaps a hobby. But a degree or a career? Impossible! From that moment I immediately changed all my degree options and set myself on a path to becoming an ecologist.

I had a second light bulb moment while studying for a master’s degree at Imperial College. I was based at the Natural History Museum in London. Suddenly all my lecturers were talking to me about invertebrates because they cover every life history strategy, occupy all available niches on earth, and exhibit the most fascinating behaviors. It all clicked. In the Natural History Museum, one of the world’s finest institutions dedicated to the study of the natural world, I realized that humans simply cannot exist without insects. It seemed like madness to pursue the study of anything else.

From those early degree days, the gradual crescendo of appreciation for natural history has crept up on me. Nowhere have I found more peace than in the quiet life of a field biologist. Rising with the sunset, spending the day conducting experiments and collecting insects, then retiring as darkness descends. Working in Namibia to collect data on ant assemblages, I lived alone, hundreds of kilometers from the nearest town with no running water, electricity, or mobile phone signal. Alone but surrounded by the teeming life of the Kalahari savannah. I would look forward to my daily visit from a young giraffe who wandered by my camp each evening to munch on acacia leaves. I’d enjoy the thrill of spotting a rogue mongoose as he popped out from the home he set up under my stove. It would soothe me to slowly catalogue the natural world around me, and no discipline lends itself better to this process than the study of insects. To be in nature is to never truly be alone—so while I may not always have loved insects, it seems we are stuck with each other till death do us part.

Heather Campbell holds a PhD in ecological entomology from the University of Reading and is a lecturer in entomology at Harper Adams University in Shropshire, UK. She is associate editor for the Journal of Ecology and has written for many leading scientific journals, including the American Naturalist and Myrmecological News. She is a National Geographic Explorer with research expertise in insect ecology, and she specializes in African ant diversity.