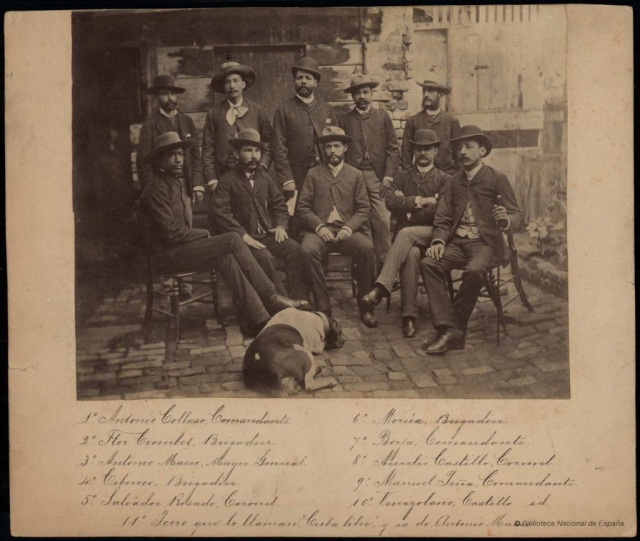

Near the end of July in 1885, General Antonio Maceo spoke to an enthusiastic audience at an assembly hall on East 13th Street in Manhattan. The general, one of the most famous leaders of the unsuccessful war for independence in Cuba between 1868 and 1878, was in the city seeking donations to buy arms and munitions for a new war. A group of volunteers, under his command, had already departed for Kingston Jamaica, where they were preparing for an invasion of Cuba. The event was one of hundreds of gatherings held by exile revolutionaries in New York in the last third of the 19th century in support of such efforts. But it sparked unusual controversy. The Spanish Consul in the United States wrote to the district attorney asking him to prohibit the gathering, arguing that it violated neutrality laws and because it was “to be attended by colored men, and presided over by the so-called Major Gen. Antonio Maceo.” The district attorney replied that there was no legal mechanism to prevent such an assembly, but the local precinct did send sixteen patrolmen to monitor the event, having received reports that it would be “disorderly.”

The accusation was familiar. The general was a man of partial African ancestry and the most prominent of the revolutionary leaders who had made the abolition of slavery and the end of racial privileges central to the project of independence. He was a target of suspicion and accusation, fomented by Spanish enemies and some Cuban participants in earlier war. The Spanish had construed the rebellion as a rising up of blacks against whites. Some white Cubans had sought to undermine or constrain his leadership. Yet the accusation also points to an important point. Cubans of African descent did, in fact, constitute a large proportion of the exiles who participated in and supported the expedition in 1885. There is no record of exactly who was in audience that cheered for the General that evening, and raised nearly 12,000 dollars, under the watchful eye of the New York City patrolmen. But many Spanish-speaking New Yorkers, of African descent, were certainly in attendance.

These early Afro-Latinx migrants, and their impact on Cuban and Puerto Rican revolutionary politics, are the subject of my book, Racial Migrations: New York City and the Revolutionary Politics of the Spanish Caribbean. I have been able to document the emergence, by the middle of the 1880s, of a well-organized community of black and brown cigar makers, seamstresses, waiters, cooks, laundresses, and midwives, who had begun to settle and build institutions within the segregated apartment buildings of Greenwich Village. Indeed, at the time of Maceo’s appearance, in July of 1885, some prominent members of this community had already shipped out to Kingston as part of the expedition. Several weeks after the general’s speech, the community gathered at the third annual Cuban-American Picnic. Organized by the Logia San Manuel, the picnic drew together Cubans of color with African American friends and neighbors. Dance music –likely some combination of Cuban danza and the local sounds that would later be known as ragtime—was provided by Pastor Peñalver, a young Cuban recently graduated from the “colored” high school on Manhattan’s West Side.

The man who came to serve as the spokesman for emigres of African descent was a cigar maker and writer, originally from Havana, named Rafael Serra. Serra volunteered for the expedition in 1885, was commissioned as Lieutenant, and spent two years in Jamaica and Panama waiting to deploy before returning in disappointment to New York. Once back in the city, he mobilized the Logia San Manuel and other independent networks and institutions established by migrants of color to support the struggle for black civil rights in Cuba. He recruited them to participate in Republican Party organizing in New York. He mobilized them to create an immigrant educational society, designed to support the entry of men of color from Cuba and Puerto Rico into the professions. He and his wife, a midwife named Gertrudis Heredia, allied with the white poet and journalist José Martí, to recruit white and black workers into the Cuban Revolutionary Party under the banner of “a nation for all.” When Martí died in 1895 and Maceo died in 1896, they drew on the same New York community to support a struggle to preserve the democratic values of the party. And, finally, in 1902, Serra returned to Cuba, where he became one of the most successful black politicians in the early republic, twice winning election to the House of Representatives.

Racial Migrations traces the trajectories of Serra, Heredia, and other migrant revolutionaries as they traversed and confronted distinct local systems of racial domination. It explores the politics they articulated, the coalitions they built, and the compromises they made as they participated in nationalist projects that, famously, promised to transcend racial division. The book contends that this idea of a nation without race, and the political system that emerged under its banner, so often imagined as having sprung fully formed from the mind of José Martí, can be better from the vantage point of the migrants who gathered to cheer Antonio Maceo in New York, who joined the 1885 expedition, who created the Cuban-American picnics, and who, only later, chose to throw their support behind Martí.

Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof is professor of history, American culture, and Latina/o studies at the University of Michigan. He is the author of Racial Migrations, A Tale of Two Cities: Santo Domingo and New York after 1950 (Princeton).