For those readers who do not believe that fairies are real, they should think twice, for the extraordinary Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Comtesse d’Aulnoy (1650–1705) did not only invent the term fairy tale (conte de fees) and create tales about fairies, she was a fearless fairy herself. Forced to marry as a teenager, she joined with her mother in 1669 in a plot to assassinate her dissolute husband. The plot failed, and she was imprisoned. By 1670, Mme d’Aulnoy was pardoned because her role in the conspiracy could not be proved. Once she was released from prison, she temporarily entered a convent for refuge, which she left in 1672. During the next thirteen years, she traveled a great deal and allegedly spent time in England, Flanders, and Spain. Otherwise, Mme d’Aulnoy would occasionally return to Paris, but there are actually no records or clear evidence about what she did during this period of her life. It remains a mystery, and even the best historians of French literature have never been able to detect what Mme d’Aulnoy did.

I suspect that she studied magic with the fairies and returned to Paris to start some sort of fairy revolution.

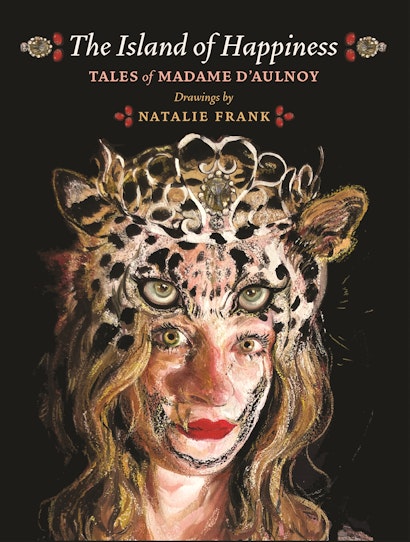

Yet, all that we truly know, I admit, is that, about 1685, she bought a house on the rue Saint-Benoît, and was gradually accepted into Parisian high society. By 1690, she published her first important novel, Histoire d’Hypolite, comte de Duglas (The Story of Hypolitus, Count of Douglas), which was a great success and contained her first major fairy tale, “L’Ille de la félicité” (“The Island of Happiness”). She followed this book the same year with a pseudo memoir, Mémoires de la cour d’Espagne (Memoirs of the Spanish Court) and in 1691 with her travel/epistolary narrative, Relation du voyage d’Espagne (An Account of a Journey to Spain), which included another fairy tale, “Histoire de Mira” (“The Story of Mira”). It is clear that she was already influenced by the fairies she had encountered during this time. The proof lies in her tales.

Once fully settled in Paris, d’Aulnoy became one of the most popular and notable authors of her time. She was invited to various literary salons and established her own salon on the rue Saint-Benoît, where she often read her fairy tales before they were published. It became customary at d’Aulnoy’s salon to recite fairy tales and on festive occasions to dress up like characters from fairy tales. She herself was regarded as a talented storyteller and eventually began publishing several volumes of fairy tales: Les Contes des Fées, I–III (1696-97), Les contes de Fées, IV (1698), and Contes Nouveaux ou les Fées à la Mode, I–IV (1698). Altogether, she published 25 fairy tales during her lifetime. More than Charles Perrault, the renowned writer of fairy tales, it was d’Aulnoy who influenced other writers with her magic pen, especially other aristocratic women, who called themselves fairies and often rebelled against King Louis XIV.

Of all the numerous writers who dabbled in fairy tales, d’Aulnoy was the most fearless and certainly the most feminist, probably because she had studied with the fairies. “The Ram” and “The Green Serpent” are d’Aulnoy’s two most interesting commentaries on what manners a young woman should cultivate in determining her own destiny—and I should like to recall that the power in all her tales is held by fairies, wise or wicked women, who ultimately judge whether a young woman deserves to be rewarded. In other words, if there is a divinity or transcendental god, it is not the Christian patriarchal god, but a powerful female fairy or a group of fairies.

The issue at hand in “The Ram,” “The Green Serpent,” and other fairy tales is fidelity and sincerity, or the qualities that make for tenderness, a topic of interest to women at that time. Interestingly, in d’Aulnoy’s two tales, the focus of the discourse is on the two princesses, who break their promises and learn that they will cause havoc and destruction if they do not keep their word. On the other hand, the men have been punished because they refused to marry old and ugly fairies and seek a more natural love. In other words, d’Aulnoy sets conditions for both men and women that demand sincerity of feeling and constancy, if they are to achieve true love. Nothing short of obedience to the rule of “fairy” civility will be tolerated in d’Aulnoy’s tales. The tenderness of feeling was definitely a goal that women sought more than men during d’Aulnoy’s times, and her two tales that discuss the proper behavior of young aristocrats have an ambivalent quality to them that make for interesting reading. D’Aulnoy projects the necessity for women to decide their own destiny, but it is a destiny that calls for women to submit themselves to a patriarchal code that is not really of their making. Thus, while d’Aulnoy wants the fairy tale to have the social function of serving women’s interests, there is an ambivalent side to the manner in which she represents these interests. Active submission to a patriarchal code qualified by tenderness does not lead to autonomy, and in fact, though there is this call for female autonomy throughout most of her tales, it is the prescribed taming of female desire according to virtues associated with male industriousness and fairness that marks the morals attached to the end of each narrative. Of course, it should not be forgotten that d’Aulnoy makes young men toe the “fairy” line of civility. That is, she is extremely critical of forced marriages and makes all her male heroes obey a code of decorum that demands great respect for the tender feelings of the aristocratic woman. Most of all, she never abandons her fairy creed.

Jack Zipes is the editor of The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (Princeton) and The Great Fairy Tale Tradition. He translated and wrote the introduction for The Island of Happiness: Tales of Madame d’Aulnoy.

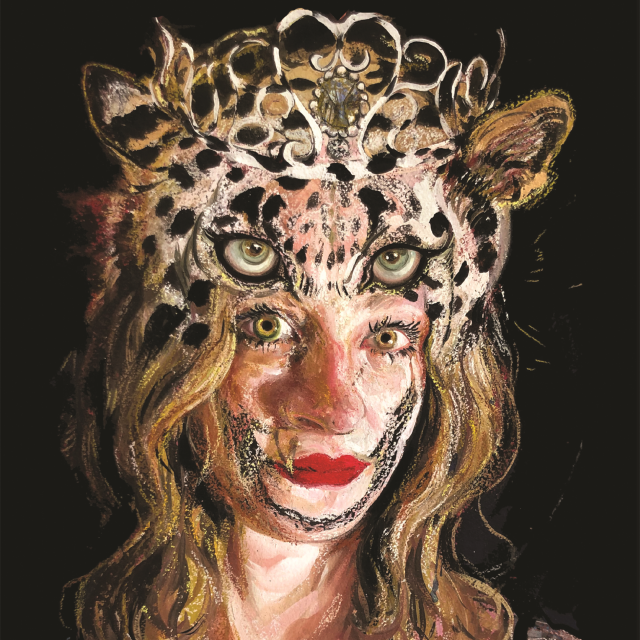

Natalie Frank is an American artist based in New York City. Her work is held in numerous collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Blanton Museum of Art. Her books include The Island of Happiness: Tales of Madame d’Aulnoy, Tales of the Brothers Grimm, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and O. Instagram @nataliegwenfrank