Geopedia is a trove of geologic wonders and the evocative terms that humans have devised to describe them. Featuring dozens of entries—from Acasta gneiss to Zircon—this illustrated compendium is brimming with lapidary and lexical insights that will delight rockhounds and word lovers alike.

Geoscientists are magpies for words, and with good reason. The sheer profusion of minerals, landforms, and geologic events produced by our creative planet demands an immense vocabulary to match. Marcia Bjornerud shows how this lexicon reflects not only the diversity of rocks and geologic processes but also the long history of human interactions with them.

Geopedia is part of Princeton’s growing “Pedia” series of pocket-sized books on natural history and science. What made you interested in contributing a volume on geology?

MB: Rocks and words are my two great passions, so writing a book about words used to describe rocks (and other geologic wonders) was the perfect project for me.

Words and rocks are alike in that both have rich back stories. Learning the etymology of a word opens a window onto earlier times and alternative ways people have thought about the world. Understanding the origin of a rock or landscape, in turn, reveals other versions of the world itself. And knowing the origin of words for rocks, landscapes, and other earthly phenomena sheds light on the relationships various human cultures have had with the natural world at different times in history.

I love the compact size of the Pedia series books; they remind me of the iconic Golden Field Guides I pored over as a child, which seemed to contain all the knowledge in the cosmos. The Pedia series is in some sense a nostalgic nod to those classics but takes the genre in a lively new direction. Each Pedia book is like a carefully curated, delightfully designed museum exhibit—except without the aching feet and the pricey gift shop at the end. And every entry is, well, an entry—no ticket needed.

That prompts the question: Is Geopedia meant to be read from A to Z?

MB: It can be, but that’s not the only way to navigate the book. At the end of the text for each entry, I point the reader to related terms—e.g., the piece on ‘thixotropy’, or sediment liquefaction, is linked with entries describing other surprising behaviors of mud and sand. One could start from any arbitrary point and then follow the cross references to take a zig-zagging path through the entire book. I’ve also created appendices that organize the terms into several groups, including topical themes, geographic locations, biographical eponyms and—my favorite—languages of origin.

So the terms you include aren’t just recent neologisms coined by scientists?

MB: Not at all. The geologic lexicon reflects not only the prodigious diversity of rocks and geologic phenomena but also the rich history of human experiences with them over the last ten millennia.

The glossary of geology is a gallimaufry of modern scientific terms mixed with words—some embarrassingly anachronistic—from mythology, alchemy, mining, and mountaineering . It also includes imports from scores of world languages, based on the premise that people who have direct experience of a particular geologic phenomenon are in the best position to describe it. Some examples include erg, an Arabic word for a vast sea of sand; and lahar, from Javanese, meaning a thick, fast-moving, and dangerous slurry of volcanic ash mixed with water.

I understand that for outsiders, geologic terminology can seem opaque and a little off-putting. Chemistry, at least, has consistent rules about naming compounds, and biology uses Linnaean taxonomy to impose order on the unruly multitudes of organisms. But in Geopedia, I’ve chosen to celebrate the profligate idiosyncracies of the geologic lexicon. Perhaps geoscientists can be forgiven for being such magpies for words; the sheer profusion of things invented by this ingenious planet demands an immense vocabulary to match.

Will readers come away from Geopedia with anything more than the lexical equivalent a handful of pretty pebbles?

MB: I certainly hope so. Although this short book is not intended as a systematic introduction to the geosciences, nor a comprehensive glossary of the field (the American Geosciences Institute publishes such a volume and it runs to more than 39,000 entries), it should give readers a kind of pointillist portrait of the planet.

I’ve deliberately selected the entries in Geopedia because they provide windows into larger geologic stories—of remarkable places, strange incidents, dramatic plot twists in the planet’s history, misconceptions about geologic phenomena, colorful characters who contributed to the geosciences, and the remarkable biographies of selected rocks, minerals and landforms that every Earthling should know on a first-name basis.

Why does it matter if people know the names for things like a “thalweg” or “yazoo” (to choose two entries related to rivers)?

MB: Quite simply, one doesn’t notice or value what one doesn’t have words for. Acquiring a vocabulary to describe the natural world helps sharpen our vision of it—and also highlights the parts we still we don’t understand.

To geoscientists, rocks and landforms are far more than inert curios, they are evidence of Earth’s ebullient creativity, its capacity for ceaseless reincarnation of primordial matter into new forms. They are transcripts of eons of conversation between the solid Earth and water, air and life. They are both fascinating archives of the past and our best windows into the future.

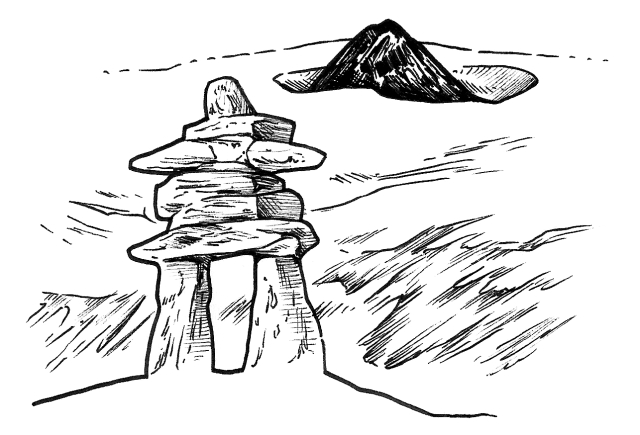

Sadly, some geologic phenomena—and the words that describe them—may become relics of the past as climate changes. A poignant example is nunatak, from the Inuktitut language of the Canadian Arctic, meaning a mountain peak that sticks up above a thick blanket of glacial ice. As the planet warms, and polar landscapes are laid bare, that word will survive as a memory of how the world once was.

Marcia Bjornerud is professor of geosciences and environmental studies at Lawrence University and a contributing writer for the New Yorker, Wired, the Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times. Her books include Timefulness: How Thinking like a Geologist Can Help Save the World (Princeton). Haley Hagerman is a graphic artist and the illustrator of Timefulness.