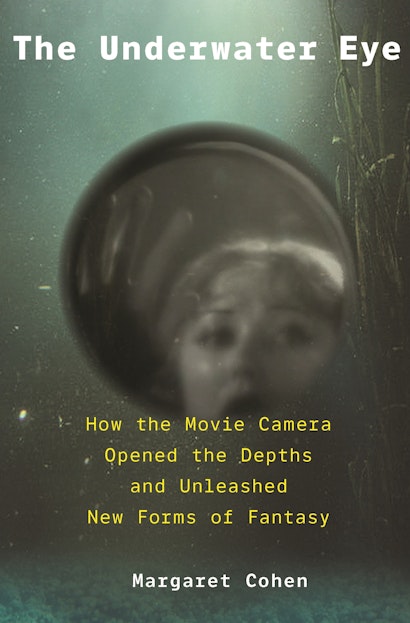

In The Underwater Eye, Margaret Cohen tells the fascinating story of how the development of modern diving equipment and movie camera technology has allowed documentary and narrative filmmakers to take human vision into the depths, creating new imagery of the seas and the underwater realm, and expanding the scope of popular imagination. Innovating on the most challenging film set on earth, filmmakers have tapped the emotional power of the underwater environment to forge new visions of horror, tragedy, adventure, beauty, and surrealism, entertaining the public and shaping its perception of ocean reality.

What was your biggest surprise when researching the book?

MC: That industry used helmet diving gear across the nineteenth century, certainly from the 1830s, for salvage and engineering. Yet, neither scientists, nor governments, nor general publics, for that matter, were curious to go below. This indifference coincided with the first wave of what the Victorians called “aquaramania” that had spread around the globe by the 1880s. The British Empire famously ruled the waves in the nineteenth century, marine biology was flourishing, oceanography was expanding as a scientific discipline as well—and people were indifferent to using technology to descend into the depths. Philip Henry Gosse is a celebrated naturalist-engineer who installed the first public aquarium at the Zoo in London in 1853. Gosse had heard of scientific diving off Sicily by a French biologist, Henri Milne-Edwards, but he dismissed these experiments. Maybe at some level he sensed the competition. Aquariums, after all, are artfully curated marine gardens whose conditions have little to do with the reality of underwater environments.

When did this indifference start to ebb?

MC: With the invention of underwater photography, and above all underwater film. It’s commonplace that we live in an age dominated by images, but it took the ability to see the underwater realm for people to realize its fascination. Reliable underwater photography dates to the 1890s, and in 1912, the American J.E. Williamson figured out how to enclose a camera operator in a submersible, and let audiences see what was going on beneath the water’s surface. The invention of underwater film is a case where the medium fits the message. Film is uniquely suited to convey particularly alluring qualities of underwater reality, such as how bodies glide, and how our perception is disoriented. And then of course, there’s the chance to see marine life in its element. Audiences waxed enthusiastic about underwater wonders from Williamson’s first documentary, The Terrors of the Deep (1914)—which, for example, let people for the first time see sharks from below. William Beebe was a famous American naturalist adventurer who published a full-length book about diving off Haiti, Beneath Tropic Seas in 1928, with a photo of a barracuda taken from one of Williamson’s films. “You had planned to tell others about it but you suddenly find yourself wordless,” Beebe wrote. If you’ve ever gone snorkeling off a coral reef in good health, how do you find words for the subtleties of its colors and its extraordinary life forms?

What are some of the challenges facing underwater film makers?

MC: Working there to start. To quote Richard Fleischer, director of Disney’s 1954 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea—“the sea is there to defeat you.” The underwater environment is really an alien planet that we access from our shores. Its environment is toxic and hostile. People can’t breathe water and we can’t see clearly without a layer of air that permits light waves to refract in an intelligible fashion. The conditions, even near the surface, are very low light, and pressure intensifies by about one atmosphere for every 10 meters of depth. Just staying warm in its dense atmosphere is yet another challenge. Across the book, I’ve chronicled the role of new technologies in permitting underwater capture and how creative filmmakers used the qualities of the environment, as well as the access and limits of technologies to create powerful emotional effects.

Emotional effects … such as?

MC: Across my history, filmmakers have such fun—okay, they struggle, but they also have such fun—with what I call liquid fantasies. Here’s one distinctive aspect of the environment that’s immensely generative—the hazy quality of seeing underwater. It can be used to create gloom or mystery—or to add glamor in showing the body. The underwater haze has been a way for filmmakers to be quite suggestive and even evade censorship. Take the iconic credits designed by Maurice Binder for Thunderball that appeared in 1965, where naked women swim provocatively—this is a film that somehow succeeded in receiving a general-audience rating.

Another immensely generative effect is the difference between looking at the surface of the water and seeing what’s going on in the depths. In Jaws, Steven Spielberg amplified the difference to the length of blockbuster film, capitalizing of course on the reality of sharks as apex predators and also age-old fears of monsters in the depths. At the surface, calm—and below, the vulnerable bodies stalked from the shark-eye view. When I was researching Jaws, I came to understand that Spielberg’s horror fantasy of shark carnage distorts marine reality with potentially harmful real-world consequences. In fact, the number of people who die from white shark attacks every year is miniscule. Further, some species of sharks are now endangered, and they’re apex predators, really critical to ocean health. But the liquid fantasy of Jaws is hard to dislodge. I was just looking at the New York Times Sunday section today (Oct. 20, 2021), and the cover article is “Fear on Cape Cod as Sharks Hunt Again,” with a font and colors that look like they came off a Jaws poster. In fact, fear-mongering aside, filmmakers and marine biologists alike are working to create comparably vivid imagery that would convey the value of sharks to our blue planet.

From age-old fears to Jaws: what’s the continuity from pre-cinematic to cinematic representations?

MC: Well of course, discovering actual undersea creatures and conditions is transformative. The 21st century is seeing a revision of the human imagination of the octopus, for example, long thought monstrous, and now being shown as highly intelligent and even perhaps sensitive. That revision dates to the scuba era. Cousteau and others found the creature inoffensive compared to its fearsome reputation, and indeed rather shy. And then, with color film, audiences could see the octopus’s captivating continuously changing hues that suggested it experiences emotions.

That said, there is also continuity, in part due to features of the environment like its atmosphere fatal to humans. Edgar Allen Poe imagined a drowned “City in the Sea” with a Gothic mood and Gothic aesthetics have inspired filmmakers exhibiting shipwreck footage, from Cousteau’s first film shot with scuba Epaves (1943), to the wreck sequence in Cameron’s Titanic—and then there’s Jacques Tourneur’s War-Gods of the Deep, a 1965 sci-fi/surrealist remake of Poe’s poem. One more reason for continuity is that filmmakers are figuring out how to exhibit a realm that has never been shown. Seeing their processes turning this novel planetary environment into representation was a fascinating aspect of my research. Cousteau was the first to name the experience diving in depths at the limits of compressed air when the diver experiences a potentially fatal high that Cousteau called rapture of the deep. When Cousteau and Malle took viewers down with divers to film in these unprecedented depths in The Silent World—they reached 247 feet—how did they organize the footage? According to the conventions of German expressionism and film noir!

Underwater or Undersea?

MC: Both. I initially was focused on the role of film in expanding audiences’ abilities to imagine the undersea. But then I realized that there were some very powerful fantasies set underwater that really have nothing to do with the marine environment. There’s the swimming scene in Creature from the Black Lagoon with scientist Kay and Gill-Man. It’s set in a lagoon, so freshwater, but there’s also a romantic beauty to the aquatic pas-de-deux of unrequited longing that would inspire Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water. Another example is the memorable scuba scene in Mike Nichols’s The Graduate set in a backyard swimming pool in Pasadena. In a one-and-a-half minute take, we follow Benjamin’s viewpoint through a diving mask as he walks burdened with scuba gear from his parents’ kitchen into the pool, and then looks up at them through the water. From this viewpoint, they appear distorted in a memorable expression of twisted suburban reality.

What do you hope your readers take away?

MC: First of all, that they appreciate what I call the underwater film set: that the submarine environment offers raw material for memorable fantasies, that further are shaped by technologies for filming there and by the human imagination. There’s a robust body of criticism going back to Marx on how the arts are shaped by social conditions. It’s only recently that we’ve realized we need to take account of the physical environment as well. So that’s a methodological point—to appreciate environmental conditions as among the material factors shaping the arts. We’re able to recognize that now, obviously, framed by the urgent realization in the age of the Anthropocene that we need to figure out (more sustainable) human relations to the planet.

Along with appreciating imagery created in the depths, I hope my readers realize that the underwater realm belongs to our world, even if it’s hidden from view. It’s commonly said that we know less about this area covering almost ¾ of our planet than Mars, despite all the work being conducted there—undersea cables, offshore drilling, submarines, and so on—and despite its vibrant life that moreover sustains our own. I end my book with the BBC Blue Planet 2 because this immensely influential series used new camera technologies to reveal not just unseen mysteries of the undersea but climate devastation. I also end with Blue Planet 2 because the producers and filmmakers went to great lengths to portray the sea as pristine wilderness where humans’ main role is as destroyers, alleviated by some heroic conservationists. I think one of the great challenges for filmmakers today is to tell stories that include humans in the picture in more nuanced fashion and that enable us to imagine a human relation to the oceans where we too are its inhabitants.

Margaret Cohen is the Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization at Stanford University, where she teaches in the Department of English. Her books include the award-winning The Novel and the Sea and The Sentimental Education of the Novel (both Princeton), as well as Profane Illumination: Walter Benjamin and the Paris of Surrealist Revolution. She is also the coeditor of The Aesthetics of the Undersea and general editor of A Cultural History of the Sea. She lives in Stanford, California.