The companion website, developed with support from Princeton University Press’s Global Equity Grant, supplements The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur’s Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century. While taking the book to broader audiences, the website features objects published and studied for the first time in-depth. Thanks to the generous permission granted by the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, Bikaner, this book website makes the seventy-two feet long and eleven inches wide painted letter sent from Udaipur to an eminent Jain monk in 1830 accessible for research across disciplines. This artifact presents as a rich archive and critical lens for looking at the history of Indian painting and letter writing; expanding the purview of non-European, vernacular accounts redolent with aesthetic moods and affective experiences; exploring material genres associated with mapping and mobility; and assessing the role of religious, mercantile, and artistic communities in shaping political diplomacy and territorial claims in early colonial India.

I first encountered a snippet of the seventy-two-foot-long painted invitation letter as a four by six-inch reproduction in Susan Gole’s pioneering Indian Maps and Plans (New Delhi: Manohar, 54). No measurements were noted. Yet, I imagined the scroll’s spread—it motivated me to abandon archival research in the British Library and travel to Bikaner at short notice in April 2009. Housed in the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, maintained as the personal library of the renowned scholar of Jain religion and culture, Dr. Abhaychand Nahata, I never anticipated the extent to which this artifact would impact my research. As the librarian, Mr. Chopra, helped me carefully unfurl the scroll, held together by a spindle on either end in an openable glass box, Udaipur’s painted streets, shops, and sights were revealed. At any given instance, I could examine only a two-foot section of the scroll. I attempted to retain the painted vignette past my line of vision just as we stack storefronts in our memory while walking through a busy bazaar. Similarly, the composite image, presented within the rectangular window of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), invites you to scroll digitally up and down the screen to unfurl the paper scroll (Fig.1). You are enticed to imagine the streets strolled and routes followed by Udaipur’s local painters to render their city visible as a charismatic place par excellence.

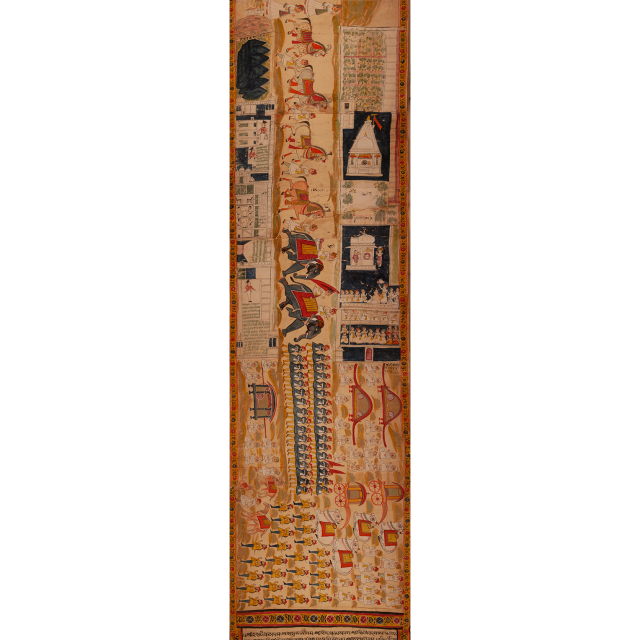

The material format of a scroll stimulates a feeling of anticipation. It constitutes and amplifies the very genre of the vijñaptipatra, an invitation letter. Such letter-scrolls were made in order to encourage prominent religious figures to travel to a distant city in the upcoming monsoon season by circulating an urban imaginary of that city as a thriving place—politically, culturally, religiously, and economically. Prominent merchants of the local Jain community hoped their invitations would evoke emotions of awe and abundance. Over the first 65 feet of the 1830 Udaipur vijñaptipatra scroll, an unnamed artist creatively mapped a principal street of the city, painting its important palaces, temples, and bazaars. The last three feet of the scroll preserve the signatures of more than twenty-five prominent merchants of the city of Udaipur, each written in a distinct hand. The text of the letter, inscribed by pandits Rukhabhdas and Kushalchand, prefacing the signatures, employs poetic renditions in Sanskrit and the regional Gujarati and Rajasthani dialects to eulogize the invited monk. The scribes end the letter by emphasizing the emotions and eagerness of the devotees, the residents, and the ruler of Udaipur—we are told they remembered the eminent monk day and night just as a peacock awaits the arrival of the rains. As we digitally scroll across the length and breadth of the composite image of Letter of Invitation Sent to the Monk Jinharsh Suri—created by digitally stitching more than 100 images—a feeling of anticipation is recreated. As we zoom in and out to examine the shopkeeper’s wares, compare the painter’s outlines, and read the scribe’s notations, we are invited to consider how the scroll was held, viewed, and read by the monks.

Now—more than ever—we are reminded simultaneously about the material limits and the endless potential of the digital medium. Before I embarked on this digital project, I initiated my study of the 1830 Udaipur vijñaptipatra scroll by pasting printouts of my photographs to produce a facsimile. The scroll’s artists had joined together multiple sheets of paper of approximately two feet in length in order to create such a painted letter. Considering even this simple step in the scroll’s assembly, one confronts multiple questions: Did a master artist draw the complete composition, to be followed by other artists from the workshop, who filled in colors in parts of the scroll? Or did the artist paint the scroll in a continuous manner, addressing a manageable length of two to three feet at a time? If artists indeed worked in this manner, how did they manage to conceive an all-encompassing cityscape as a unified picture? The discontinuities that are part of viewing such a scroll and the distortions that become part of the surface of paper over time seem ironed out on the screen. On the one hand, the scroll’s composite image engenders modes of dialogical viewing. It can enable new paths of research and imagination between the material scroll, the urban space, and the pixelated screen. On the other, the seemingly parallel and delimited digital scroll and the paper scroll are ultimately entirely distinct and discontinuous mediums in how they demand our bodies, hands, and eyes to maneuver this artifact and gather a sense of the place and time it relays.

I returned to Udaipur and walked with my letter-scroll in the summer of 2010. The painted mohallās (neighborhoods) of the utensil-sellers and cloth-sellers that sprawl across scroll’s spine and the city’s streets today reinforced my recognition of the 1830 Udaipur vijñaptipatra scroll as a bazaar image that formulates a vernacular mapping practice. The scroll painter translated images and mixed pictorial tropes seen in Udaipur court’s paintings; he departed from the typical metaphorical reference to a bazaar seen in earlier letters by reinforcing the specificity of each trade and individual. Most significantly, the scroll conveys a sense of the street and the everyday as well as a plethora of spatial stories that one encounters in urban places. Such cultural economies of praise for the flourishing city, and circulation of its image as charismatic, provide an alternative to the view that circumscribed popular maps in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which adhered to British colonial narratives of political decline and disintegration in this time period.

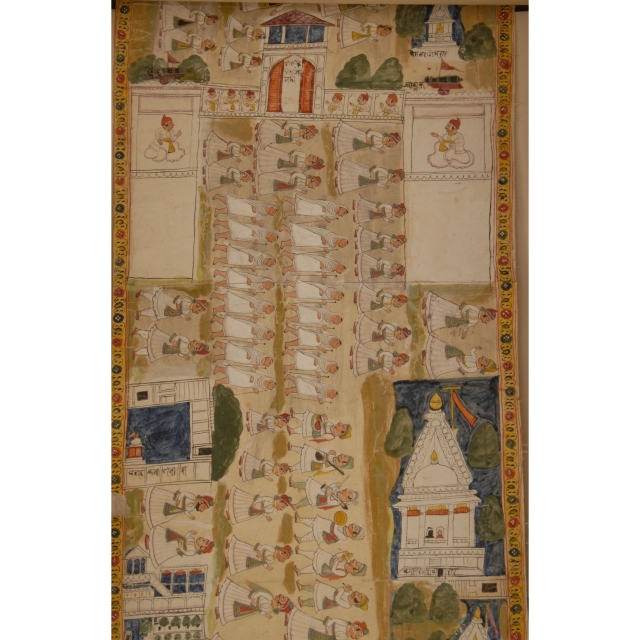

Whether Jinharsh Suri arrived during the following monsoon season in 1831, bringing the change and prosperity that are projected in the pictures and the letter, is not known. What is interesting and instructive is that the artist of the scroll does not leave the question of the invitation’s acceptance open-ended, as the writers of the letter did. The scroll painter added an elaborate procession to the center of the scroll, depicting the Udaipur Maharana Jawan Singh (r. 1828–38) and the British colonial agent Alexander Cobbe, creating an unusual and innovative dual axis—a long spine that is intersected continuously by horizontal cells—along which a viewer constantly navigates in order to see and understand the work. The final pictorial vignette in the scroll imagines that this invitation would be effective—its objective realized by the monk’s arrival.

On one side of the central street, in the most striking way, the artist pictured and labeled the assembly to be held by the invited leader, Jinharsh Suri, who is depicted as someone who was established in the city rather than as an aspirational visitor. On the other side, the artist labeled sites of the British residency, such as the “Sahab’s Bungalow” and the “cantonment of the foreigner (fīrangī).” The artist carefully depicted courtyards with green lawns and the home’s inhabitants seated in chairs, thus marking differences between the lifestyles, furniture, and cultural protocols of the British agent and the Udaipur ruler, who was shown seated on floor cushions. Groups of elites, palanquins, and troops are depicted waiting upon both the monk’s durbar and the British residency. With this evocative image, the artist could have been directing the invited Jain monk to imagine himself in a position of authority in Udaipur. In imagining this anticipated religious assembly precisely opposite the British residency, and pictorially matching its scale, the artist presented colonial and religious powers as two equal and competing domains of authority.

When I followed the painter’s footsteps to locate Udaipur’s British residency, it emerged that the surrounding area was transformed into an important Jain neighborhood by 1832–34. Significantly, the merchant Joravarmal Bapna, who played a key role in commissioning the painted invitation sent in 1830, built a temple there, and his portrait was prominently painted on the entrance wall. This portrait was rendered in the same style as the contemporary Udaipur ruler Jawan Singh’s portrait on the scroll, which suggests that the artist may have been one and the same, or at least from the same workshop or artistic milieu.

I invite Udaipur’s residents, contemporary visitors to this city of lakes and sprawling bazaars, and any curious students and scholars to unfurl the scroll, examine the details of the painted precincts and sense the mood of the featured places, to find new sites and stories as they walk through the city’s streets. This website is created to discover and think with these little studied and viewed artifacts. The anticipation and enchantment you may feel upon digitally scrolling the composite, in turn, may lead you to deliberate the entangled emotions and expectations of the merchants who sent the scroll and the monks who received it as an invitation to travel to the city of Udaipur the following year.

Dipti Khera is associate professor in the Department of Art History and the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Twitter @KheraDipti

Also of Interest

In the mood for art in India’s eighteenth century by Dipti Khera.