Successful writing projects have their tri-partite biographies, informed by the life histories of writer and subject matter and their productive encounter. Some of them are slowly formed while others are the result of a sudden insight or discovery. The Last of Its Kind: The Search for the Great Auk and the Discovery of Extinction belongs to the latter category. It took me by surprise. What was it that got me hooked? I wasn’t looking for further research at this point. My diary indicates that in 2018 (a year before I reached legal retirement age) I was alerted to several recent sources on the fate of the great auk (Pinguinus impennis). Some of these inspiring works cited the manuscript The Gare-Fowl Books, five notebooks written by British naturalist John Wolley (1823–59) during his expedition to South-West Iceland in the summer of 1858. It was stored at Cambridge University Library.

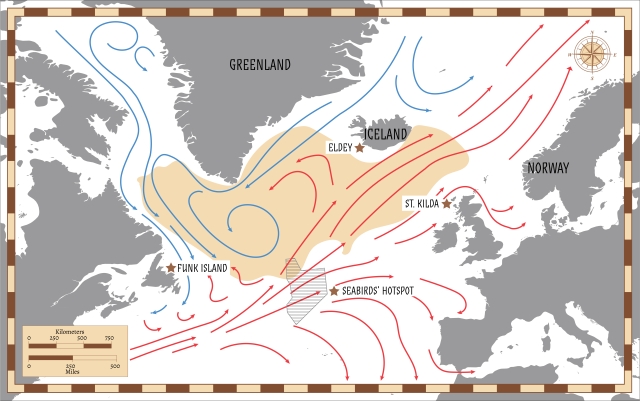

I was deeply curious and asked a colleague based in Cambridge to request access to the manuscript. Would it be accessible and readable? Several scholars seemed to have cited it or used it, but no one seemed to have explored it in detail. My colleague checked it and sent me a few photos. I was immediately struck, knowing that the last great auks which had roamed the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean for millennia were killed in Iceland in 1844. Wolley’s handwriting, I realized, would be difficult to read, but his text was bound to offer an important avenue into an historic extinction.

The manuscript could not be borrowed or copied for legal reasons, but I managed to negotiate access by buying high-resolution images of the lot, 900 pages. It was an expensive deal, but I was passionately interested and happily signed an agreement with the library. About ten days later I downloaded the images and began to explore their contents, based on interviews with the last hunters of great auks. During the following months I immersed myself into the text, struggling with the handwriting at first. I reckoned this material had to be written up, in a book that situated Wolley’s text in the Victorian age and Icelandic peasant society, focusing on its potential relevance for modern environmental politics and concerns.

This took five years, and several visits to significant sites, natural museums, and libraries. Mid-course I was surprised to learn that Wolley mentioned several farms and place names which were central in my anthropological fieldwork in the area in the 1980s. It mattered that a close relative of the great auk, the Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica), was considered festive food during my childhood in the Westman Islands, Iceland. Children would both enjoy the delicious meat and rescue the helpless pufflings as they got stuck, an ironic predicament shared with nineteenth-century naturalists and collectors. More importantly, it eventually dawned upon me that Wolley’s trip to Iceland and his manuscript signaled the birth of unnatural extinction, extinction caused by humans.

Wolley died a year after the Iceland expedition, but his travel companion Alfred Newton (1829–1907), a Cambridge zoologist, drew public attention to the fate of the great auk. While the flightless bird had been hunted at many coastal sites as part of subsistence economies, it began to seriously decline in the wake of massive slaughtering at Newfoundland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Later it became extinct as a result of escalating demands for skins and eggs for museums and private collections in Europe and North America. At the time of Newton’s writings, biological writings on extinction (a relatively recent term in the natural sciences) focused on the fossil record and the distant planetary past. Newton insisted that extinction was an ongoing process here and now and that it could, and should, be avoided. This paved the way for current concerns with mass extinction, one of the side effects of the so-called Anthropocene.

On hindsight, my rather sudden commitment to the plight of birds on the brink resonated with my intellectual past. Not only had I engaged with environmental issues for years, I had also been deeply interested in relations between humans and other animals—the other-than-human and multispecies relations, in academic jargon. Other animals, including birds, are not just good to eat or to think with, as symbolic vehicles, they also matter in a genuine social sense. This took me on a memorable tour to the Cosquer Museum at Marseille, France, where humans had carved iconic images of great auks on cave walls. These are the earliest known images of great auks, created some 27.000 years ago.

My great-auk narrative, it turned out, invited fundamental questions, notably about the species concept, the idea of extinction, and the place of the narrator. Alfred Newton’s trick, as American historian of science Henry M. Cowles has shown, was to introduce a radical distinction between natural extinctions, typically prehistoric extinctions established through studies of the fossil record, and unnatural ones, recent extinctions caused by humans. This allowed him to carve a space for environmental concerns and animal protection informed by scientific expertise, a novel development in the Victorian Age.

Now, however, the broad field of extinction studies has moved beyond Newton’s dualistic framework, challenging conventional ideas of observation, privileged expertise, and autonomous species. The distinction between the natural and the unnatural has collapsed as human impact is increasingly inscribed in the “natural” world. Mass extinction, I argue, represents an unnatural collapse of the natural. At the same time, species and speciation (still notoriously difficult to define and understand) are no longer at the center of extinction studies as organisms are increasingly seen as relational and embedded in ecosystems. What gets lost with extinction is not just an organism, in the strictest sense, but a way of life and a network of relations.

Wolley and Newton joked as they left for Iceland that this was a “genuinely awkward expedition,” keeping in mind the medieval notions of “awk” (probably a reference to the cry of the great auk) and “awkward,” something that is strange, neither upward nor downward but sideways. Indeed, it was in a sense; they hoped to find great auks but found none, suspecting the species had vanished. The expedition, however, played an important role in the discovery of unnatural extinction, placing it on the expanding environmental agenda by the end of the nineteenth century.

Gísli Pálsson is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Iceland. In addition to The Last of Its Kind, he is also the author of The Man Who Stole Himself and The Human Age.