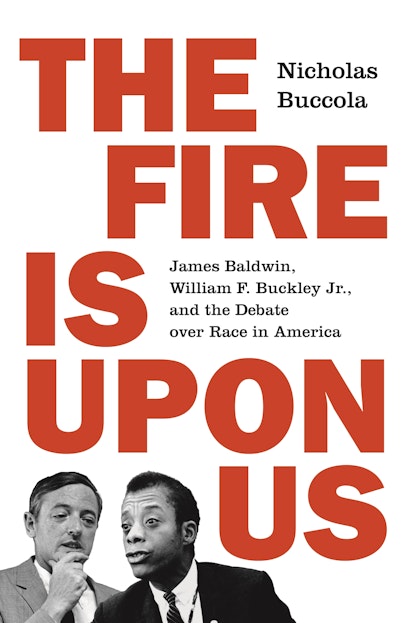

On February 18, 1965, an overflowing crowd packed the Cambridge Union in Cambridge, England, to witness a historic televised debate between James Baldwin, the leading literary voice of the civil rights movement, and William F. Buckley Jr., a fierce critic of the movement and America’s most influential conservative intellectual. The topic was “the American dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” and no one who has seen the debate can soon forget it. Nicholas Buccola’s The Fire Is upon Us is the first book to tell the full story of the event, the radically different paths that led Baldwin and Buckley to it, the controversies that followed, and how the debate and the decades-long clash between the men continues to illuminate America’s racial divide today.

“The Fire Is upon Us” comes from an interview that James Baldwin gave in the Transatlantic Review. What does that phrase mean to you?

NB: In The Fire Next Time (1963), Baldwin played the role of warning prophet, calling on his fellow countrymen to take responsibility for their history in order to escape the “racial nightmare” they had created. Despite the quasi-apocalyptic title, The Fire Next Time is actually a fairly hopeful text. The problems Baldwin identifies in the book run deep, but he concludes that we have it within our power to save ourselves from the fire. By the time of this interview in 1970, Baldwin’s hope had diminished considerably as a result of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the election of Richard Nixon, the stalling of the civil rights movement, and the war in Vietnam, among other things. When Baldwin spoke of the fire that was upon us by 1970, it is important to note he had in mind both political and moral destruction. Even if the country had successfully “fended off” the “doom” of complete political disintegration as the interviewer put it in the question to Baldwin, the country had not fended off the doom of moral disintegration. The state of our souls was always at the forefront of his mind.

What surprised you most about Buckley and Baldwin in researching them for this book?

NB: I was surprised by the depth of Buckley’s moral failure on race matters. I considered myself to be a conservative / libertarian through my college years so I found myself in circles in which Buckley was lionized. As I grew out of right-wing politics, I still held Buckley in relatively high regard as a “thinking man’s conservative” who ultimately repented from his “blind spots” on race. The deep dives into the archives I did for this project led much of that respect to dissipate. What I discovered was not just that Buckley collaborated with some thoroughly white supremacist characters, but that he saw to it that white supremacy was baked into the pillars of the conservative movement he was so instrumental in building. Buckley’s failure was deepened by the fact that when he had doubts about white supremacy, he was careful not to communicate those doubts publicly in ways that might alienate the racist right. As far as Buckley’s late-in-life repentance on race, I demonstrate in the book that this is all-too-often overstated.

“What I discovered was not just that Buckley collaborated with some thoroughly white supremacist characters, but that he saw to it that white supremacy was baked into the pillars of the conservative movement he was so instrumental in building.”

What surprised me most about Baldwin is the almost super-human empathy he had for ordinary white folks who thought they benefited from the politics of racial hierarchy. Baldwin’s insistence that we try to see the world through the eyes of these folks has been dismissed as “faux-generosity,” but it is anything but that. From his earliest days in public life, Baldwin held the view that the supposed beneficiaries of white supremacy were in fact also its victims. Baldwin thought there was nothing more pathetic than the poor white person who clung to the fantasy of white supremacy as the foundation of his sense of self-worth. Folks like this were being sold a bill-of-goods by elites who were the real beneficiaries of the systems of exploitation white supremacy supported. Baldwin’s empathy did not extend to these elites (Buckley included), who knew precisely what they were doing. Few ideas from the book are more resonant with contemporary American politics than this one.

There’s a particularly tense and charged moment during the Buckley-Baldwin debate where Buckley states his intention to treat Baldwin not with the “unctuous servitude” of recognizing him as a black man, but as “a fellow American,” (i.e., a white man). How did this moment strike you as you attempted to give it context?

NB: That is a very telling moment indeed. It really captures the lens through which Buckley viewed Baldwin. Buckley conceded that Baldwin was a talented writer, but he believed that Baldwin’s fame had far more to do with white liberal guilt than it did with his merit. White elites, Buckley argued, bow before Baldwin and accept his “flagellations of our civilization” without ever daring to challenge him. This failure to challenge Baldwin, Buckley argued (following Garry Wills, who had made this point in his review of The Fire Next Time in National Review), showed him profound disrespect. Whites were refusing to challenge Baldwin, the argument went, because he was black. Once could only respect Baldwin if one was prepared to treat him as a “fellow American” or, Buckley explained, as a “white man.” Buckley’s “unctuous servitude” is revealing, though not precisely in the ways he intended. Buckley’s association of “American-ness” with whiteness is consistent with years of writing on race. In his most infamous piece on race, “Why the South Must Prevail,” the South really means “the white South.” Buckley almost always thought about black people as “problems” that happen to be in one place or another (e.g., the South, “America,” South Africa, etc.)

One last point is worth making: there is great irony in Buckley’s claim to respect Baldwin’s arguments as a “fellow American.” What Buckley reveals during the debate and in decades of writing about Baldwin is that he never took the time to read him carefully and take his arguments seriously. One of the student questioners during the debate – captured in the Appendix to the book in the never before seen complete transcript of the Buckley speech – calls him out on this and Buckley’s response is telling. The student, it is clear, has read Baldwin carefully and knows that Buckley has not. Rather than taking the student question seriously, Buckley dismisses him with a joke. In the laughter that filled the chamber, the student’s point may have been lost: Buckley did not respect Baldwin enough to take his ideas seriously.

Baldwin won the debate that night, but you still managed to write a 440-page book about it and the years leading up to it, shedding light on Baldwin and Buckley’s pasts alike. How do you manage to take a nuanced look at this debate when our society seems to have accepted the achievements of the civil rights movement as cornerstones of American democracy?

NB: When I was first pondering this book, I imagined a short narrative history of the debate, much like similar projects that have been published about Malcolm X’s trip to debate at Oxford in 1964. It did not take long after I began research for the book that I realized that something more than a “snapshot” was needed. What made more sense to me was to treat the debate as a climactic chapter in a longer story about how two prominent public intellectuals thought through (and participated in) the civil rights and conservative movements. Because Baldwin and Buckley were contemporaries and such prolific writers, they proved to be the perfect subjects for this sort of analysis. As the political world is in a state of tumult around them, there they are day after day sitting at their typewriters, recording, interpreting, and often shaping history. In sum, I do not think one can really understand what happened that night at Cambridge (and why it matters) without trying to understand how the worldviews of the debaters had developed over the previous two decades.

“Baldwin helps us understand why we ought to have some doubts about whether we have ever really accepted the apparent achievements of the civil rights movement.”

On the question of the enduring relevance of these apparently settled matters in American democracy, I think the key word in your question is “seems.” While many achievements of the civil rights movement are “celebrated” in a superficial way, Baldwin would remind us that our commitments to the ideas at the core of these achievements never ran very deep. This is something that Baldwin saw from the beginning. He found himself in the relatively awkward role of skeptic at every moment of apparent triumph in the civil rights revolution. Baldwin was, of course, thrilled to see the movement achieve judicial, legislative, and electoral victories. But he was always there to remind us that true liberation would not come until we came to terms with our history and took responsibility for it. Baldwin helps us understand why we ought to have some doubts about whether we have ever really accepted the apparent achievements of the civil rights movement.

What do you hope that readers take away from the book?

NB: There is plenty to be said for the study of history for its own sake. There is something essentially human about immersing ourselves in the lives and times of others in order to understand why they did what they did, why they thought what they thought and so on. Even if there were no obvious ways in which the story of “Baldwin versus Buckley” was relevant to our own time, I think it would be worth telling.

But in addition to enjoying and learning from this as a historical project, I hope readers take away valuable political lessons. One of my intellectual heroes, Judith Shklar, described political theory as an enterprise that occupies the ground between history and ethics. One reason to study the past, Shklar thought, is to better understand how we ought to live in the present. The story I tell in this book helps us understand how we got where we are today and I hope it helps us sort out what we ought to do next.

Nicholas Buccola is the author of The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass and the editor of The Essential Douglass and Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Salon, and many other publications. He is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, and lives in Portland.