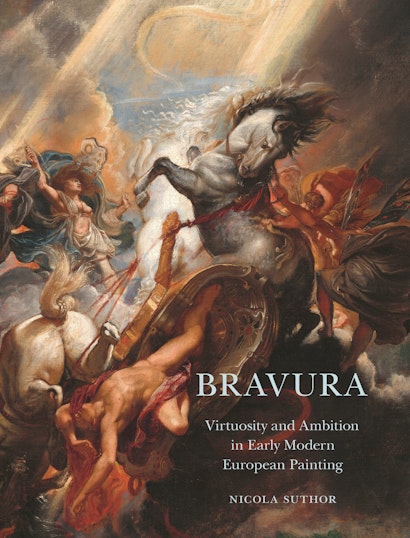

The painterly style known as bravura emerged in sixteenth-century Venice and spread throughout Europe during the seventeenth century. While earlier artistic movements presented a polished image of the artist by downplaying the creative process, bravura celebrated a painter’s distinct materials, virtuosic execution, and theatrical showmanship. This resulted in the further development of innovative techniques and a popular understanding of the artist as a weapon-wielding acrobat, impetuous wunderkind, and daring rebel. In Bravura, Nicola Suthor offers the first in-depth consideration of bravura as an artistic and cultural phenomenon.

Your book is the first investigation into the bravura style. How did you come up with the topic?

NS: In my dissertation on Titian’s sensuous paintings, which dealt, among other things, with the critical reception of the visible brushstroke in Venetian painting in 16th- and 17th-century art literature, I came across a set of astounding metaphors in art criticism that likened Venetian painting to warfare. I realized that what connects excellence in both of these “arts” is manifested in the word “bravura.” Stemming from the adjective “bravo,” which generally speaking expresses the recognition of an accomplishment (we still use “bravo!” in the same sense today), bravura’s more bold conception is tied to the noun “il bravo,” meaning a “hired assassin.” Thus a celebration of “execution” in both senses of the word is the common ground here. My book on bravura takes a deeper look at the martial metaphors used to describe extraordinary painterly achievements and what exactly they are describing. Interestingly, not only the art critics of the time but the artists themselves promoted this bold artistic concept by representing themselves on canvas not with the tools of their craft, but rather with dagger or sword in the attitude of a bravo, or by signing their works in a spectacular manner on a prominently displayed sword or other instrument of execution.

Is Bravura a glorification of violence?

NS: We might say so. Not for the sake of violence tout court, but for the sake of art. The artist as “bravo” challenges the ethical role model of the courtier as celebrated in the Renaissance, whose agreeable habitus reflects his willingness to adopt the socio-cultural conventions of the courtly world in order to climb the social ladder. With the bravo attitude, painters defied this assimilation and instead claimed self-empowerment. This was necessary because the art market changed significantly during the same time period. Most artists had no secure employment and were more or less what we would call “freelancers”—a modern word that also bears a martial undertone—the “lance”—at its core. One bone of contention was the value of the artwork, which artists fought, quite aggressively, to maximize. In order to expose their “execution” and promote their art in often very competitive contexts, bravura painters worked quickly and in a highly economical and performative fashion, which allowed patrons to watch them not only work but produce a complete artwork in a short timespan. Another form of recognizing execution was the emphatic understanding by contemporary art critics of the visible brushstroke as exposing the science of painting. But the ostentatious exposure of artistic means was highly rhetorical and predominantly utilized to impress, astound, and dazzle the beholder, rather than to instruct them. This was clearly a risky undertaking, and the book also gives insight into the precariousness of the artistic claim inscribed in the bravura gesture; the book tells the story of its ups and downs.

Let’s speak about the “downside” of Bravura!

NS: The downside has been most vividly described by the spokesmen of the academic tradition. They dismissed the bravura style as anti-academic and anti-intellectual, and also vilified it as highly dangerous for budding artists because bravura’s spectacular painterly manifestations promised a short cut on the path to gaining mastery, leading instead, according to these critics, to a developmental impasse. The aggressive tone of their response tells us a lot about the impact bravura had on the definition of so-called “high art.” The primary issue was bravura’s impromptu aspect; although based on a profound knowledge built by long practice, a knowledge present in the open brushwork, this is not necessarily readily apprehensible. Painterly bravura is, from an academic perspective, a deceitful and superficial phenomenon. We might characterize it as a tightrope walk: it has the potential to be the highest expression of art or, when it fails, to be art no longer. This is bravura’s downside that can compromise but also incite its highest aspirations.

What is the material basis of your argument?

NS: Art literature from the 16th to the 18th century, and close analyses of central artworks that manifest the forms and themes of bravura in an exemplary way. The treatises are full of legendary accounts of bravura’s feats and artistic attitudes, but because bravura is overtly anti-academic, there is no treatise that sets out a theoretical basis. The book’s many detailed analyses thus contribute to the definition of an art concept that is drawn from practice.

Do you think that the concept of Bravura is also applicable to modern or contemporary art?

NS: Yes, I do. The revival of painting and its rhetorical gestures in contemporary art speaks for the topicality of bravura. I am thinking, for instance, of Katharina Grosse’s immense installation “It Wasn’t Us” in the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, which monumentalizes the heavily loaded brushstroke and the explosive potential of color. And although my narrative of bravura only considers the early modern period of European painting, it ends with a few pages on the afterlife of bravura and how its anti-academic attitude and aggressively combative stance show up again in the 20th century. There are of course significant differences between the two centuries, or as I would say, fundamental modifications of the concept of bravura. The highly praised “gaucherie” of Cezanne, as the father figure of modern painting, seems to overtly contradict any claim of virtuosity. But this new paradigm for artistic originality and truthfulness opposes bravura only at first glance because many of the early modern bravura artists were reproached for having no proper artistic foundation, no “disegno.” Their performative way of painting made them the forerunners for what will be defined as self-reflexive in modern terms.

Nicola Suthor is professor of art history at Yale University. She is the author of Rembrandt’s Roughness (Princeton).