It was cool among the Tamarisk and they misted on me lightly. I sat, hugging my legs to my chest, chin resting on my knees. I resisted the urge to swish away the bugs exploring my ears and eyebrows. My mind wandered to other places. Lunch. School the next day. I ignored the sweat collecting in the crooks of my knees, and the way it tickled the backs of my calves. Why was I here again?

I am not a patient person. I am a now person. The first thing I look at when contemplating a new recipe is how long it takes to make. I want to know how the story ends before the third chapter. I prefer two-day shipping to ground. Diets aren’t for people like me.

I remember well when my dad taught me the value of a pause. He, an avid birder, had taken me with him to look for spring migrants. We wandered the edge of a lake, he stopping every few feet to eye some new movement among the Tamarisk (Salt Cedar) that lined the beaches, me kicking at rocks and thinking about being somewhere else. I was bored, distracted, and hinted repeatedly at how far from the car we had come.

“Did you see that one?” he exclaimed while holding his binoculars to his eyes. “Western Tanager I think.” he looked to me for a second opinion. I didn’t even have my binoculars to my eyes. “What’s wrong with you?” he chided.

I mumbled some lame excuse about a bunch of boring old Tamarisk trees. He stared at me incredulously, then instructed me to follow him. We walked to the center of the Tamarisk grove where he pointed to the ground.

“Here. Sit down. I’m leaving for 15 minutes. Don’t move. We’ll talk about it when I get back.”

Slightly peeved, but mostly curious at the strange request, I sat. In retrospect, he may have left me there just so that he could have 15 uninterrupted moments of bird watching.

Now, nearly 30 years later, I am a biologist, focusing on flowers and bees. I find the art of holding still—not moving for 15 minutes—is essential to my practice. Staring at flowers as they wobble in the wind is the only way to see the very tangible moment when an ecological connection is made between that flower and its pollinating bee.

What’s more, I find that holding still is essential to my well-being. In a world of immediate gratification and one-click buying options, where images on the television change every three seconds, and where constant social media status updates are the norm, I know that I am incentivized to perpetually multi-task. And while I am comfortable with the constant stream of information, the comfort comes at the expense of a quiet moment. Holding still, outside, gets me out of my head and reminds me of my blessed insignificance.

The contributions of citizen scientists to the body of natural knowledge used by professional scientists, surprisingly, also rely on a slow meander out the door. Not to run, or rock climb, or mountain bike, all of which are fine pursuits, but just to look around. Kick the dirt. Hold still. Wait and see. Document. Remember that the world doesn’t always move as fast as television would make it seem. That the drudgery and horror of a pandemic hasn’t been noticed by the birds. That the bees rummaging in the flowers in my yard are moving at the same speed that they did when my father was a child. Nature resists the social revolution in which we find ourselves, and provides a standard against which to judge the present.

I grew up at the cusp of this great change in our social structure. My children, on the other hand, have been born into it. They have few opportunities to learn the important skill of waiting, of delaying gratification, and of focusing for more than a minute. I am teaching them that if they don’t get outside, they won’t see ‘it’. And when they ask me what ‘it’ is, I say, as my father did to me, “We’ll talk about it when you come back.”

Three Lazuli Buntings, the color of jewels and rainbows, flew into the grove and proceeded to squabble, completely unaware of my presence. A Western Tanager flew to a perch somewhere over my head and serenaded the world. I contemplated turning to get a better look when I heard a noise beside me. Slowly, ever so slowly, I moved my head. There, sharing the shade of the Tamarisk grove with me, was a jack rabbit. Not five feet from my hunched self, he stretched his back legs out behind him, pressed his belly into the cool dirt, laid his long ears flat across his back, and closed his eyes. I could see the hair on his rump was ruffled, I could see the nick in his ear, and I could see how very big his nose was. Why was I here again? For this moment. This was it.

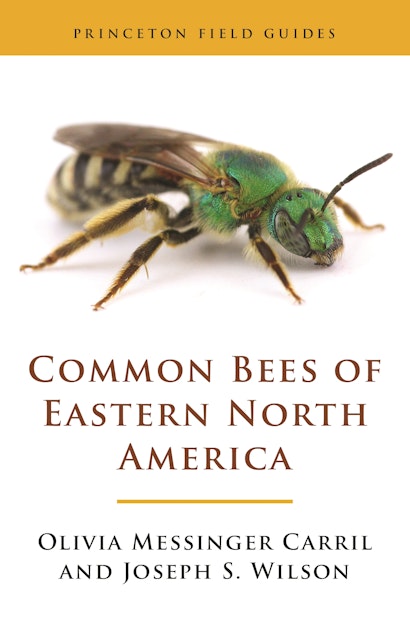

Olivia Messinger Carril is an independent scholar who has been studying bees for more than two decades.