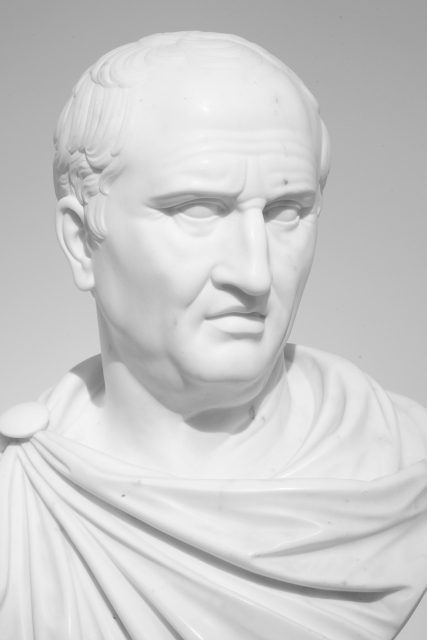

Psychotherapy is not a recent invention. Thousands of years before Freud, Greek thinkers had discovered the seemingly magical effects that words can have to soothe the mind. “There surely exists a medicine for the soul,” wrote Cicero, the great statesman and philosopher of ancient Rome, in his Tusculan Disputations. “It is philosophy.”

Cicero should know. When he wrote these famous words, he had just used philosophy to rescue himself from profound grief. His beloved daughter had just died at the age of 32 from complications of childbirth, and he fell to pieces. He couldn’t find a way back.

The death of a child is the ultimate test. A child’s death tests our faith, our resolve, our hopes, even our will to live, and no pill or surgery can restore them. But philosophy, says Cicero, can. Consolation can offer us hope that death isn’t the end. That we’ll see our loved ones again in heaven, and hug and kiss and hold them once again.

In a desperate attempt to heal his grief, Cicero turned to classic treatises on coping with grief from ancient Greece. He studied them, meditated, and sought out examples of men and women who had survived grief before. Then, he lifted his pen and wrote a famous self-help essay to himself. He called it the Consolation.

That essay is long gone, but it was credibly re-created in the Renaissance from true sentiments Cicero expressed elsewhere. And when the future president John Adams (1735–1836) read the re-created treatise in August of 1796, he commented that it is “remarkable for an ardent hope and confident belief of a future State.”

What did Adams mean? Adams, who was a devout Christian, was struck by Cicero’s ardent belief in heaven—that’s what he means by “a future State”—and that Tullia was in it, enjoying everlasting life. Throughout the re-created essay, Cicero declares that his daughter is in heaven. He is sure of it. That she is up there, looking down, happy, safe, and waiting for him. That she, and eventually he, would live forever. “My precious Tullia,” he writes, “if you can hear me in death—you’re happy. By dying once, you put an end to all the unhappiness you faced in life. You’re sheltered now, safe and secure.”

Christians, such as Adams, can turn to the Bible for evidence and hope of life after death. Cicero, who was assassinated in Rome 43 years before the birth of Christ, had no such luck.

Nevertheless, Cicero believed in heaven all the same. He was confident it awaits us after death, but not because the Bible or any other authority told him so.

For Cicero, life after death was not an article of faith. Evidence that we’ll live again consisted not of promises and religious revelations, but of observation and cold logic and reasoning and the weighing up of probabilities. For example (as he explains in the Tusculan Disputations), our bodies grow cold when we die, which suggests the soul is warm. Heat rises; therefore, it will continue to rise through the atmosphere until it reaches equilibrium. When it does, there will be all those who died before us. That is what we call heaven. The soul will have gone back to God, who gave it.

What makes us think the soul doesn’t just evaporate and scatter upon death? Cicero admits that that’s a possibility, and if so, then game over—but in a good way. In that case, death means the end of all heartache and pain. Death is a blessing.

Nevertheless, Cicero finds plenty of other reasons to think the soul doesn’t evaporate when we die, and he reviews them in the Consolation. For example, our souls seem to be almost magical. They move and work faster than anything in the known universe. Souls analyze problems and foresee outcomes instantly—outcomes we’d need generations to test in the real world. And unlike anything else on earth—including our bodies—the soul initiates its own motion. It remembers. And it’s always active, even in sleep. All this points to a divine origin of our souls.

Furthermore, all the art we create and the scientific endeavors we pursue suggest we care about what happens after death. If we didn’t, why do we bury our loved ones as we do?

No one wants to die, says Cicero. But death is the only way to reach life everlasting, so we shouldn’t fear or resent it. In fact, we should welcome death, especially since it’s unavoidable.

Regardless of our religion—our lack thereof—these thoughts may still comfort us in times of sorrow. In case it’s not obvious, however, these are not arguments and chains of logic to work through when you or a loved one are in the throes of grief. You would be a fool to preach atheism to a mother or father at their child’s funeral.

In fact, Cicero addresses this very point in the first sentence of the book:

I know the experts say not to treat recent traumas, and that in human life, no tragedy should strike us as surprising or unexpected. Still, though, I have to try—if there’s any possible way—to fix myself, and stop my world from caving in.

That rule, which Cicero proceeds to break out of desperation, ultimately goes back to a brilliant Stoic psychotherapist named Chrysippus. As he and his fellow Stoics taught, we shouldn’t wait till we get to that point. It’s too late to reach for help managing your anger in the heat of the moment. Just so, the time to reflect on death, grief, and immortality is now—before tragedy strikes. Because, as Cicero puts it in the re-created Consolation,

The more often tragedy strikes, the more intimately human we must think tragedies are. We must think of them as virtually congenital, bound up with human nature.

The point is this: you should read his arguments now. Because tragedy is coming. If we prepare for it, though, we’ll find a way through.

Michael Fontaine is professor of classics at Cornell University. His books include How to Tell a Joke: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Humor and How to Drink: A Classical Guide to the Art of Imbibing.