I bought a doughnut and they gave me a receipt for the doughnut; I don’t need a receipt for the doughnut. I’ll just give you the money, and you give me the doughnut, end of transaction. We don’t need to bring ink and paper into this. I just can’t imagine a scenario where I would have to prove that I bought a doughnut. Some skeptical friend? ‘Don’t even act like I didn’t buy a doughnut, I’ve got the documentation right here. Oh wait, it’s back home in the file… under ‘D’ for ‘doughnut.’

You, like legendary stand-up comedian Mitch Hedberg, probably have a stash of receipts documenting superfluous transactions. Your wallet and coat pockets are likely filled with crumpled testaments to the gallons of milk you bought last month, the coffees grabbed-to-go on the way to work, the library book you renewed. If you laughed when you read Hedberg’s joke, it’s because you believe that transactions like this, whether they involve doughnuts or not, don’t need to be documented, let alone preserved for posterity.

Why do these records matter? The doughnut receipt might be a little more complicated than Hedberg’s joke reveals. Think back to the proof of your last consequential doughnut purchase. The receipt you were handed almost surely included the kind and number of doughnuts you bought, a price per unit, and the total amount your craving cost. The receipt almost surely included the sales tax you paid, marking a transaction that triangulates you, the doughnut store, and the government. It also probably displayed the last four digits of your credit card number, an important string of numbers if you hope to be reimbursed by an employer or client. Revealing financial and hunger-motivated behavior, the doughnut receipt is a remarkably rich document. It not only contains a world of information; it also makes apparent relationships between individuals and institutions.

Receipts are an example of the kinds of everyday texts that make up what I call the “functional archive.” The functional archive isn’t a conventional repository, designed to store books and papers. Rather, think of it as an abstract space in which documents interact with each other to create a network of writing, irrespective of where their physical versions are stored.

Take the functional archive that supports applying for a new driver’s license at the DMV. Compiling the necessary proof to go with your form turns into a scavenger hunt for things that you’ve not looked at in ages and inevitably can’t find the night before your appointment. To be entered into your state’s database, where you will join the pantheon of others who are permitted to drive, you need at least:

- a passport: proof of identity

- a utility bill (in hardcopy): proof of residence

- proof of your Social Security Number: your W2, perhaps? Or the original card, if you can find it

- your old license, to be surrendered to the DMV

In short, documents from completely disparate aspects of your life come together to make your final driver’s license. Tying the individual to the DMV, the functional archive you assemble is a manifestation of institutional power. Without any of the required documents, the DMV reserves the right to deny you the license you seek.

Being overwhelmed by a concatenation of linked documents might seem like a contemporary condition, but as long as there have been documents, there have been functional archives. And, as the example of the DMV illustrates, functional archives are both constructed by and aid systems of power. This can look different depending on the time and place with which we’re dealing. But in the nineteenth century, a period of immense imperial expansion, the formation of the functional archive was tightly tied to the ideological project of empire building. In South Asia, the jewel in the crown of the British empire, administrators hoarded information about their colonial subjects like precious resources. Offices and publishing houses churned out military guides, handbooks, licenses, account books, and reports. To the colonizers, these objects provided a sense of security. If they could learn more about South Asia (and write about it), perhaps ruling the region would be simpler. If they could organize their subjects and track their every action, they could ensure the longevity of their empire.

As cheap printing technologies became increasingly available to the public, South Asians joined the British in generating their own functional archives, too. Local presses churned out almanacs that combined Hindu religious calendars with bureaucratic information. They distributed literary magazines, assembling collages of news articles, book reviews, and literary essays. Though different in scope, the ultimate goal of these texts was to help colonial subjects navigate a terrifying imperial landscape. If books and documents embodied British aspirations to power, they embodied South Asian aspirations to survival.

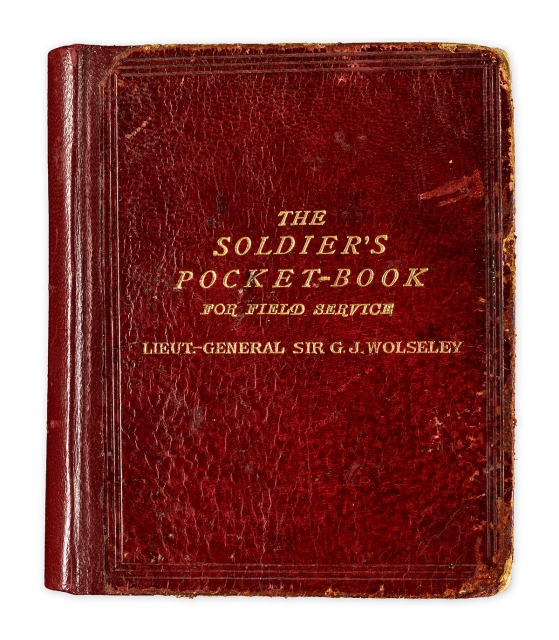

What happened to these texts in the imperial functional archive? Many of them sat on nineteenth-century bookshelves, now to be found in institutional libraries and archives. Many of them ended up being disposed of in their own time, eaten by insects or thrown away by their readers. But there’s an extended moment between the production of the texts and when they meet their ultimate destructive fates. It’s the moment in which a soldier’s handbook, The Soldier’s Pocket-book for Field Service, travels from Britain to South Asia, tucked away in the bag of a young soldier headed for the North-West Frontier Provinces. It’s the moment in which almanacs, amalgamations of religious and bureaucratic information, become scratchpads for everyday events: practicing cursive, highlighting a train route, recording the birth of a son.

In the hands of their readers, texts like the handbook and the almanac become more than just books. They become a bridge between a reader and the British empire. A minor British soldier wasn’t privy to the machinations of military strategy in India. But in his eyes, empire wasn’t a slow unfurling of an abstract ideology. It took the literal form of the Pocket-book, hiding in his bag. Office workers found themselves consulting their almanacs for railway timetables, anxious about when they could arrive at—and leave!—the office. The almanac represented both the tyranny of bureaucratic routine and the and possibility of escape.

Despite their proximity to the functional archive, imperial readers didn’t always love their reading material. But they were required to engage with it, nonetheless. The very soldiers who lugged their copies of the Pocket-book across the world also continuously trash-talked the volumes, bragging that they were useless, and didn’t need to be read. The soldiers’ angst reverberated across disparate media: Christian pamphlets decrying the devilry of war, stories by Rudyard Kipling advancing the merits of empire. Refracted through the eyes and words of others, the Pocket-book wasn’t just the Pocket-book. It was the network of representations that hung over it, like a little cloud. By considering the many different versions in which texts like the Pocket-book existed, we can begin to understand their cultural worlds, their vibrant social and intellectual lives.

The afterlives of the functional archive can be found in all kinds of places in the twenty-first century. They are in massive physical repositories, the British Libraries and government archives of the world. They are found in digital forms, preserved as part of newspaper databases you can search and scroll through. As I sifted through what remains I could find, I was constantly reminded of all the fragments and bits that didn’t survive: that were torn up and thrown away, burnt to cinder, or left to the ravages of insects until they were rendered unreadable.

Yet despite the holes in the historical record, I’m also reminded of the resilience of the functional archive, its will to live. That it thrives on forming networks and connections means that we can always track down surviving parts or nodes. What we miss can be recreated, at least in part, if we try to understand how these texts worked in the world. There’s always an old almanac in a suitcase or a handbook waiting to be discovered in a box in the attic.

Priyasha Mukhopadhyay is assistant professor of English at Yale University.