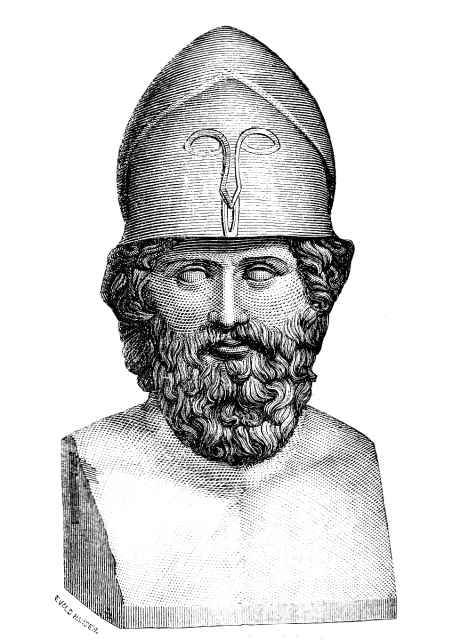

In 471 BCE, the politician and renowned general Themistocles was exiled from Athens for ten years by a vote of some six thousand Athenians. This procedure for expelling a politician from the state by democratic vote was known as ostracism from the Greek word for potsherd (ostracon) on which Athenians wrote the name of the person whom they thought needed to be removed from the state, at least temporarily.

Why was Themistocles ostracized? It seems that Athenians feared that he might engage in violence to win ascendancy over his rivals, and therefore was a threat to the institutions of the democracy. The parallel with the recent impeachment trial couldn’t be clearer and suggests a striking lesson: democratic states need mechanisms for protecting themselves against bad actors who are willing to sacrifice the very existence of democracy in their quest for power.

In ancient Athens, a vote was held annually to decide whether to send a citizen into exile for ten years. If the Athenians decided to hold an ostracism, an area in the center of the city was roped off and citizens were invited to enter and cast ballots on which they had scratched the name of the person (usually a prominent politician) whom they wished to be exiled. The citizen who received the highest number of votes was required to depart from the city, leaving his family and property behind. After ten years, the individual could return to Athens and even to active political life. Ostracism, then, was essentially a democratic way of un-electing a person for a period of time, not unlike the ban on public office holding that the Senate is now considering. Arguably, ostracism was a milder punishment since individuals were disqualified only for ten years, although the 14th Amendment allows for a lifting of the ban on public office-holding if two-thirds of both chambers of Congress agree.

While no one would advocate the introduction of Athenian-style ostracism today, its example is suggestive: strong measures are sometimes needed to protect democracies.

Paradoxically, America’s Founding Fathers abhorred ancient democracies and John Adams singled out ostracism as a particularly vivid example of the dangers of mob rule. What the Founders didn’t understand, however, is that ostracism was both a necessary and remarkably moderate mechanism for protecting the constitutional order. First, ostracism required a two-step process including an initial vote on whether to proceed, and then a vote on ostracism itself. Secondly, a quorum of six thousand Athenians (approximately one fifth of the male citizen population) was needed for an ostracism to be valid. Finally, the Athenians used the power to ostracize with restraint: only ten individuals were ostracized over a two-hundred-year period. Remarkably, ostracism seems to have been effective in protecting the constitution. Indeed, the Athenian democracy lasted for almost two centuries before it was dismantled by an external power, the Macedonians.

While no one would advocate the introduction of Athenian-style ostracism today, its example is suggestive: strong measures are sometimes needed to protect democracies. The Founding Fathers recognized this fact in the Constitution’s provisions for impeachment, and Congress and the state legislatures further acknowledged this need after the Civil War when they ratified the 14th Amendment. Another example can be found in the post-World War II German constitution. After the horrors perpetrated by the Nazis, the new German constitution established a “Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution” (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz). Even today, this agency has wide-ranging powers and may soon begin surveilling the leaders of the far-right party, Alternative for Germany, on the grounds that it is a threat to Germany’s democratic political system.

As President Biden eloquently remarked in his inaugural address, democracy is precious and fragile. As a result, we need robust, but carefully regulated, legal mechanisms for removing individuals who pose a threat to the very foundations of our democracy. Despite the claims of some Republicans that an impeachment trial in the Senate was unconstitutional because Trump is no longer president, Democratic leaders are correct that it is both constitutional and necessary. It is necessary because Trump represents an ongoing threat to the stability of our democracy due to his dangerous disregard for democratic norms. He ought to have been barred from future office.

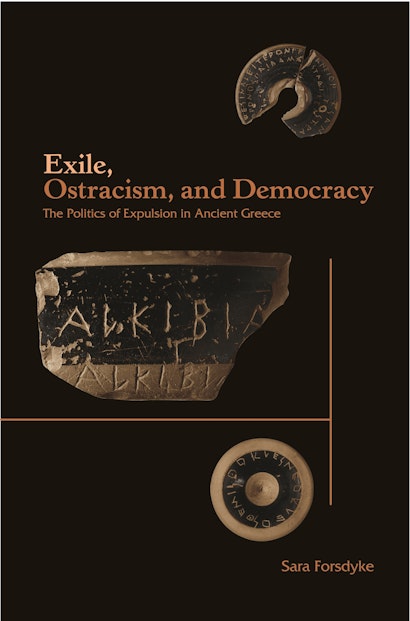

Sara Forsdyke is associate professor of classical studies at the University of Michigan. She is the author of Slaves Tell Tales: And Other Episodes in the Politics of Popular Culture in Ancient Greece (forthcoming, Princeton) and Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece (Princeton).