In the fraught years leading up to World War II, many modern artists and architects emigrated from continental Europe to the United States and Britain. The experience of exile infused their modernist ideas with new urgency and forced them to use certain materials in place of others, modify existing works, and reconsider their approach to design itself. In Objects in Exile, Robin Schuldenfrei reveals how the process of migration was crucial to the development of modernism, charting how modern art and architecture was shaped by the need to constantly face—and transcend—the materiality of things.

In broad strokes, Objects in Exile examines how emigration and resettlement defined modernism. Can you talk a bit more about the arguments made?

RS: Objects in Exile looks at the ways in which dislocation profoundly shaped the direction of art and design in the twentieth century—it argues that modernism gained coherence only after it passed through conditions of exile. Central to this idea are the trajectories not just of people, or objects, but how ideas surrounding modernism traveled—and were diverted and reshaped in new contexts.

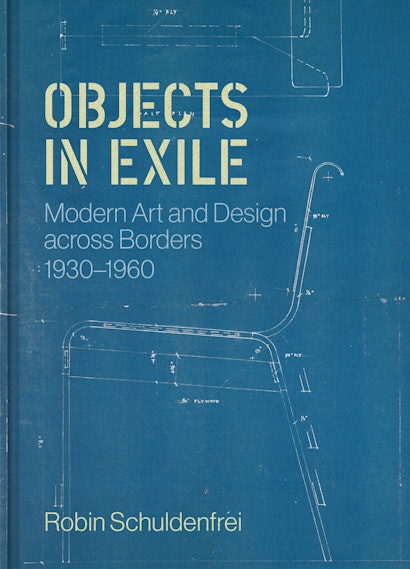

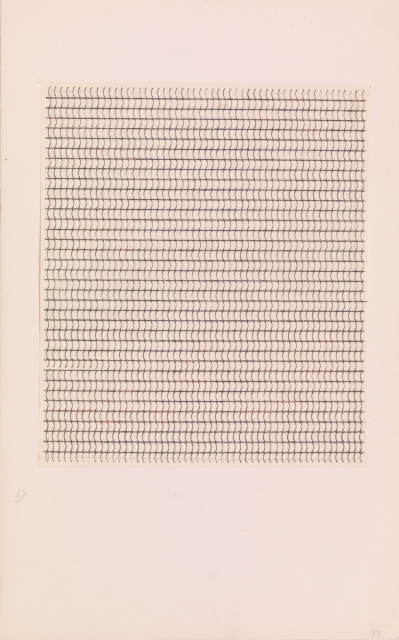

I organize the book around three arcing ideas: transposition, remediation, and contingent conditions. Transposition is the transfer of one material or idea for another in the design and artistic process, which is the mode by which we can understand how, upon his move to England, Marcel Breuer’s bent metal chairs became bent wooden chairs for the Isokon company, which specialized in wooden products. Remediation, or the changes wrought in a productive transfer between media forms, was also crucial to chart. For Anni Albers, weaving’s materiality was a springboard for other output, as evidenced by her typewriter studies (fig. 1, 2), or patterning of samples from nature such as grasses and kernels of corn at Black Mountain College.

Contingency and the conditions on the ground, as the émigrés experienced them, have an important place in this study, highlighting the productivity of friction and the unexpected events that changed the course of modernism. This section examines how modernism’s visual and material objects were disrupted because of the circumstances surrounding departure and new landings, resulting in significant new directions in art and architecture, including designs for a society and future beyond war.

Your title is “Objects in Exile,” why not their makers, e.g. “Artists in Exile”? What do you mean when you write that objects went into exile, sometimes without their makers?

RS: Modern art and design at mid-century is at the forefront of this book—exile is the catalyst for the process but it is only my jumping off point. Just as often as I am showing moments of change and new avenues, I am tracing an arc across an oeuvre that is seen as having a point of rupture; I am articulating the points of cohesion and showing the larger related context. The objects themselves are the connectors which undergird a large and complicated history.

I really see a special role for the objects that went into exile, away from their original place—and artistic context—of making, and the rise of works that changed and evolved to meet new circumstances in the US. So when former Bauhaus members fled Germany in the 1930s, what they were able to take with them formed a disproportionate part of their oeuvre thereafter. Sometimes this was purposeful, such as Mies van der Rohe’s erasure of his early Berlin output by deciding to leave that material behind in Germany. 1930s Chicago, a site of industry and nexus for the movement of goods—that avant-garde artist Moholy-Nagy landed in to start the New Bauhaus was very different than the radical Bauhaus school where he fomented his pedagogy and experimental artistic practice. With great effort (his wife referred to it as an additional child), he was able to bring his unwieldy, kinetic sculpture, the Light-Space Modulator, with him—a work more critical to expressing his theories, perhaps, than his limited English.

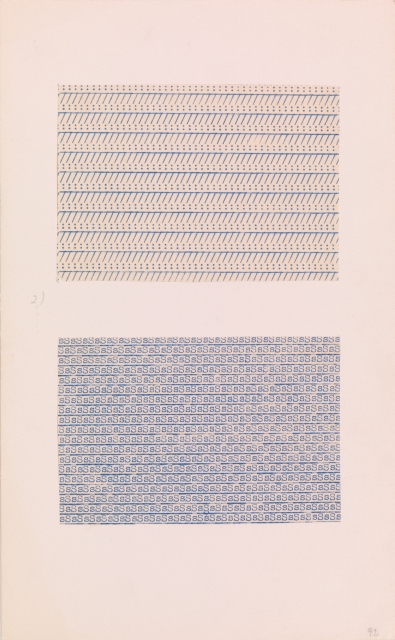

At other junctures, however, I have focused on what was no longer extant and thus previously lost to the footnotes of history. I have paid particular attention to the meaning of the missing. I have sought to find shards, sometimes literally, in the archive. The loss was caused by haste, such as Moholy-Nagy’s early left-behind canvasses (which were later destroyed by a caretaker sympathetic to the Nazis), and circumstances of departure. Photographer Lucia Moholy fled into exile in the night after her partner, a Communist Party parliament member and activist, was arrested by the Nazis at her apartment. Hastily packing just a suitcase, she left nearly everything behind, most critically her large and extremely cumbersome collection of original glass photographic negatives. What followed—in which the negatives (fig. 3) she thought lost became the core of the visual archive deployed by Walter Gropius from his new position at Harvard, in the subsequent narration of the Bauhaus—demonstrates the exigencies of exile, especially the lacunae created by objects left behind upon emigration. Photography as a medium became especially crucial to the later reception of the closed Bauhaus and what had been produced there. These Bauhaus glass negatives can be understood as going into exile separately from their maker.

Tell me more about the material conditions of work, the shards?

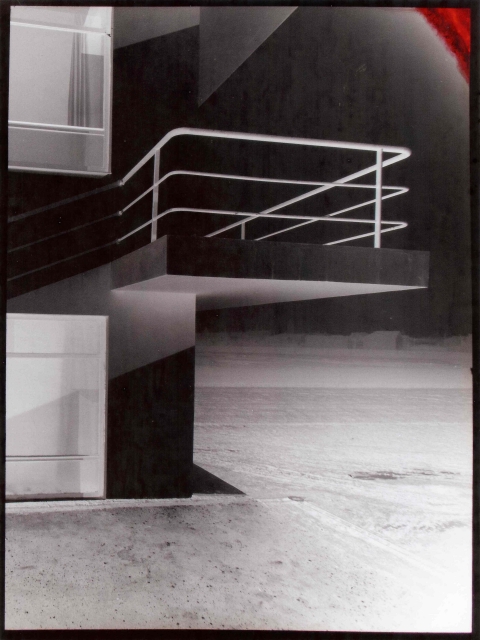

RS: The book pays special attention to the materiality of works—or its absence. While his Six Flowers photograms did not accompany Moholy-Nagy on his exilic perambulations, and the individual photograms are now lost (with one exception), he did retain a glass plate negative, now cracked, of the grouping, which, critically, gave him the possibility of making reproductions once he arrived in the US (fig. 4). In the case of Josef Albers, after the transatlantic shipment of his glass paintings arrived as shattered fragments (fig. 5), he abruptly changed course—a radical reduction in materiality, form, and subject matter took place in the subsequent planar surface of his Homage to the Square series. Flat Masonite panels were easier to work on, and less fragile, than the earlier glass.

What objects end up being the most powerful for you?

RS: Although the book focusses on modernism and the ways in which it traveled (due to the circumstances of the Nazis’ tightening of the cultural climate for modernism, and then as other avenues were cut off and artists and designers fled the conflicts of World War II), there were moments in the archive that took me away from the story of modern art and architecture. In my tracing the logistics and materiality of exile, the pathos of the protagonists’ situation would suddenly emerge in opening a new folder or lifting the tissue paper of a box in the archive. Those moments included typescript speeches Gropius gave during his initial years in England which are full of penciled diacritical marks in his hand indicating where the emphasis of particular words should lie, so that he could correctly pronounce them—“inévitable,” “áspect.” There was a box of pocket-sized notebooks which the architect Ludwig Hilberseimer used to jot down the most basic words in English. Or Lilly Reich, in the midst of quite technical and legalistic correspondence with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe about the retention of the Bauhaus furniture copyrights (which he retained as the school’s final director), missives entreating him for goods such as coffee, tea, rice, and eggs to be sent to her brother, who had numerous children at home. Beyond physical and economic hardship, there was also the continuing emotional hardship of emigration, to which an entry in the diary of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (wife of artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy) speaks: she writes of an “emigrant etiquette,” an unwritten code in which “every reference to Europe or to the past is guarded, casual, uttered only after the emotion behind it has been secured safely with an enforced dose of self-control.” And like today, families were divided by politics. Sibyl’s family of was cleaved in two as her parents and siblings, with the exception of one sister, made clear their allegiance to the Nazi party.

Given the difficulties, why did these artists decide to stay?

RS: It is significant that designers who moved from Germany, such as Gropius, Bayer, Mies, Moholy-Nagy, Marcel Breuer, and Ludwig Hilberseimer showed little desire to return after the war, despite the fact that the rebuilding of Germany would have afforded them many opportunities to practice at a large and well-funded scale. This is in contradistinction to, for example, many French artists who, as Moholy-Nagy noted with interest in the period, were “dead-set on going back to France … at the first possible moment.” Ultimately, these emigres were astoundingly successful, first they focused on contributing to the war effort, contributing novel prototypes, exhibitions and graphic design. Then, as the situation stabilized, a two-directional process of assimilation and influence began: through their teaching and the careful articulation of their theories, processes, and rationale for their work – whether art, design, photography, or architecture – the newcomers were able to find support in the US. At the same time, new ideas, materials, and modes of working in the US profoundly shaped these foreign artists and designers. It is this mutality of modernism in motion—people and objects—that Objects in Exile brings to the fore.

Robin Schuldenfrei is the Tangen Reader in 20th-Century Modernism at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. Her books include Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany, 1900–1933 (Princeton), Iteration: Episodes in the Mediation of Art and Architecture, and Atomic Dwelling: Anxiety, Domesticity, and Postwar Architecture.