The Fourth of July that mattered most to Revolutionary Boston, the Cradle of Liberty, was not the one in 1776 when the thirteen united states issued a declaration of independence to a “candid world.” Rather, it occurred the year before, in 1775, when the stakes were highest for Boston and New England, and in the form of a much quieter and little-known document.

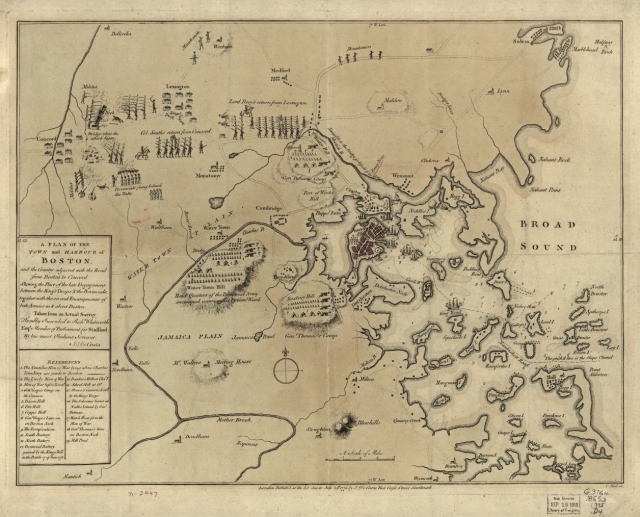

Eleven weeks earlier, on April 19, 1775, the Revolutionary War began in Lexington and Concord. General Thomas Gage sent nearly a thousand British Regulars into the countryside to seize rebel munitions and arrest rebel leaders, and thousands of New England militia, trained to respond to the alarm, came out to resist the Redcoats. By the end of the day’s brutal fighting, 273 British soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing, as were 93 colonists. The British Army retreated to the confines of the city of Boston, on the Shawmut Peninsula, where the surrounding waters of the Charles River and Boston Harbor, patrolled by the Royal Navy, guaranteed their safety. The colonial militia, numbering near 10,000, made camp in the surrounding towns—Roxbury, Dorchester, Cambridge—and began the slow process of laying siege to their own capital city.

Two months later, in mid-June, the colonial troops attempted to occupy and fortify the steep hills of Charlestown, on its own peninsula due north of Boston and separated from it by only a few hundred yards, the width of the Charles River. On the morning of June 17, the British launched a ferocious amphibious assault, which succeeded in sweeping the colonial soldiers off the heights of Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill—but at immense cost. More than 1,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded, as were 450 colonial troops, including Major General Joseph Warren, who had been the President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. The colonial forces retreated to Cambridge, where they regrouped at their encampment on the Common.

Meanwhile, the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, with delegates from twelve of the rebellious colonies (Georgia would join later), responded to the outbreak of fighting by declaring its support for Massachusetts and committing to the creation of a Continental Army to defend the Bay Colony against British aggression. Of course, at this moment, this army consisted entirely of militia from Massachusetts towns and the neighboring colonies of New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, who had rushed to the scene when the fighting began. But the Congress made the new army at least symbolically Continental by appointing the 43-year-old Virginia delegate and Seven Years’ War veteran, George Washington, as its commanding officer.

Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 2, 1775, two weeks after the Battle of Bunker Hill, and exactly a year before Congress would vote in favor of independence. The next day, he officially took command of the militia, now deemed to be the Continental Army. And on July 4, 1775, Washington issued his first general orders, inaugurating the process of transforming this loosely organized and chaotically led group of amateur soldiers into the kind of professional army that he knew from experience would be necessary to stand up to British regulars.1 These orders offer a fascinating account of what needed to be done: careful inventories of munitions, equipment, and supplies; plans for the enlistment and payment of officers and soldiers; the making of a hierarchical structure to discipline the New England militia; an attempt to diminish inter-colonial rivalries; and strict commands that “All Officers are required and expected to pay diligent Attention, to keep their men neat and clean,” including the provision of fresh straw as bedding and the careful control of latrines, or “Necessarys.” And then this odd command:

No person is to be allowed to go to Fresh-water pond a-fishing or on any other occasion, as there may be danger of introducing the small pox into the army.

It’s not that General Washington, or anyone else, thought that going fishing somehow caused smallpox. But a dangerous smallpox outbreak was sweeping through the soldiers’ encampments—it had begun in Canada the previous winter and was inching down the New England coast. Nothing could destroy an army faster than a deadly and contagious disease. For that reason a smallpox hospital to quarantine infected soldiers had been set up at Fresh Pond, at a safe distance (about a mile and a half) away from the camps on Cambridge Common. Washington’s orders against fishing or any other activity at Fresh Pond was meant to reinforce the seriousness of this threat, and together with the attention to cleanliness, lay at the heart of his campaign to prepare his army against the deadly threats of 18th-century warfare.

Washington’s enforcement of the best practices for military discipline, hygiene, and public health paid off. The Continental Army remained intact through the summer, fall, and winter of 1776, and kept the city of Boston under unrelenting siege. Meanwhile, the city itself, occupied by British troops, suffered miserably. Smallpox raged through the town, abetted by malnutrition and severe cold, with Boston’s usual food and firewood supplies cut off by the besieging army. By March of 1776, artillery reinforcements allowed the Continental Army to fortify the hills of the Dorchester peninsula, south of the city, and threaten the British position with bombardment. Unwilling to risk a repeat of the devastation of Bunker Hill, especially now that Washington had trained and disciplined the Continental Army, General Howe, the British commander, evacuated the city on March 17 without a fight.

The Royal Navy and Army would regroup and soon head to New York, where Washington marched the Continentals to meet them. But the Revolutionary War in Boston was essentially over, months before the Continental Congress reached the unanimity among the colonies, some of them quite reluctant, necessary to declare independence on July 4, 1776. For all practical purposes, Massachusetts had already been acting as an independent state for more than a year.

That the Fourth of July mattered more to Boston in 1775 than in 1776 reflects a persistent gap between the interests of Boston and much of the rest of the early United States. The plight that Boston and Massachusetts suffered after the Boston Tea Party of December, 1773, when Parliament chose to punish the colony for this act of resistance, had generated genuine sympathy among many other colonists, especially visionaries like George Washington. On June 10, 1774, Washington wrote to a correspondent in England that “the cause of Boston—the despotick Measures in respect to it I mean—is and ever will be considered as the cause of America.” But the unifying sentiment did not last. In particular, the states most strongly committed to slaveholding—South Carolina and Georgia—refused to endorse a declaration of independence that denounced the evils of chattel slavery. And the Constitution these new states compromised to create in 1787 embedded protections for slavery into the fundamental law of the land. As the issue of slavery moved to the forefront of American politics in the decades after 1787, the “cause of Boston” and the “cause of America” went their separate ways.

Mark Peterson is the Edmund S. Morgan Professor of History at Yale University. He is the author of The City-State of Boston and The Price of Redemption: The Spiritual Economy of Puritan New England.

Notes

[1] A copy of Washington’s first General Orders can be viewed here: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0027#GEWN-03-01-02-0027-fn-0007-ptr