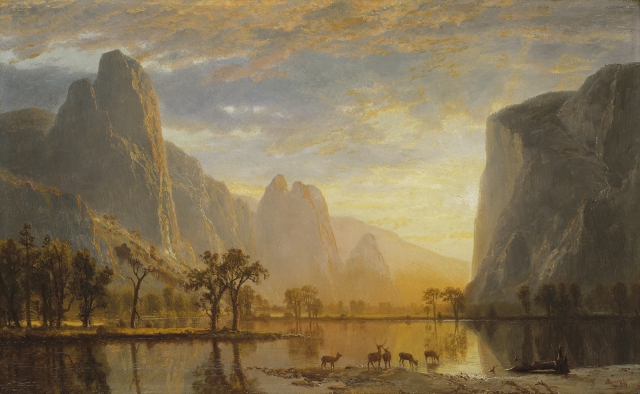

An exhibition titled Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture will be shown at the Smithsonian American Art Museum located at 8th & F Streets NW in Washington, DC, opening in 2020. (For further information visit www.americanart.si.edu.) This exhibition places American art squarely in the center of a conversation on Humboldt’s lasting influence on the way we think about our relationship to our environment. Humboldt’s quest to understand the universe—his concern for climate change, his taxonomic curiosity centered on New World species of flora and fauna, and his belief that the arts were as important as the sciences for conveying the resultant sense of wonder in the interlocking aspects of our planet—makes this a project evocative of how art illuminates some of the issues central to our relationship with nature and our stewardship of this planet.

Why Humboldt?

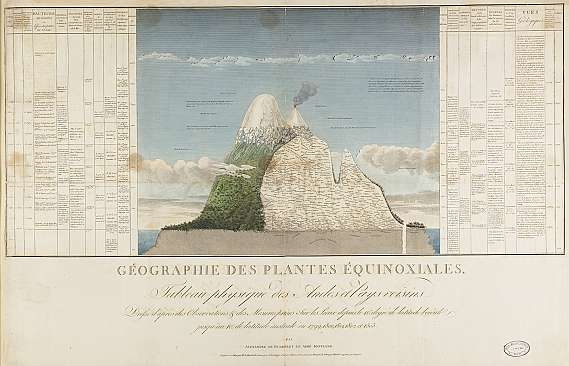

Who was Alexander von Humboldt? Why and how did his life affect the United States to such a great extent? Despite the enormity of his influence during the nineteenth century, Humboldt’s name and reputation faded in the United States after his death in 1859. Many of his new ideas simply became an accepted part of what we know about this planet; others were superseded by his colleagues and successors. However, between the 1820s and 1850s, he had become one of the best known and widely admired public figures in the world. He lived into his ninetiethyear, traveled on four continents, and wrote more than thirty-six books and twenty-five thousand letters to a network of correspondents around the globe. He had an infectious personality and boundless curiosity, surrounded himself with some of the leading minds of his era, and never stopped talking. Charismatic, annoying, exuberant, caustic, but undeniably relevant, he straddled the Enlightenment penchant for wanting to know everything about everything and the establishment of modern scientific methods designed to query that accrued knowledge. He claimed to sleep only four hours a night and called coffee “concentrated sunbeams.” [1] Among his many scientific achievements, Humboldt theorized the spreading of the continental landmasses through plate tectonics, mapped the distribution of plants on three continents, and charted the way air and water move to create bands of climate at different latitudes and altitudes. He tracked what became known as the Humboldt Current in the Pacific Ocean and created what he called isotherms to chart mean temperatures around the globe. He observed the relationship between deforestation and changes in local climate, located the magnetic equator, and found in the geological strata fossil remains of both plants and animals that he understood to be precursors to modern life forms, acknowledging extinction before many others. [2] Over the course of his adult life he developed a revolutionary theory that all aspects of the planet, from the outer atmosphere to the bottom of the oceans, were interconnected—a theory he called the “unity of nature.”

It is hard to overstate how radical an idea this was in its day. After spending more than thirty years amassing data and testing ideas, Humboldt delivered a series of lectures in Berlin in 1827, describing theories that electrified his audience. From these lectures, he began drafting the book that would cement his lasting significance, as he describes to his close friend, Varnhagen von Ense, in 1834:

I am going to press with my work,—the work of my life. The mad fancy has seized me of representing, in a single work, the whole material world,—all that is known to us of the phenomena of heavenly space and terrestrial life, from the nebulae of stars to the geographical distribution of mosses on granite rocks, and this in a work in which a lively style shall at once interest and charm. Each great and important principle, wherever it appears to lurk, is to be mentioned in connection with facts… . My title at present is ‘Kosmos; Outlines of a description of the physical World.’ … I know that Kosmos is very grand, and not without a certain tinge of affectation; but the title contains a striking word, meaning both heaven and earth. [3]

Humboldt’s singular text grew to fill five volumes, which were written in the last decade of his life to summarize all that he had learned in his scientific research. From the inaugural publication of the first volume in 1845, Kosmos—translated in English as Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe—was an international bestseller, with publishers vying for shipments of the book in at least twenty-six countries. Cosmos was translated almost as fast as it was published, was serialized in popular magazines, and inspired a generation of naturalists, explorers, artists, and authors.

Acknowledgement: This essay is drawn from Eleanor Jones Harvey, with a preface by Hans-Dieter Sues, Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture (Washington, DC, and Princeton, NJ: Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Princeton University Press, 2020). The book accompanies the exhibition of the same title at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

This piece was originally published by the Center for Humans and Nature.

About the Author

Eleanor Jones Harvey is a senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her research interests include 18th-, 19th- and 20th-century American art, notably landscape painting, southwestern abstraction and Texas art.

Notes

[1] Alexander von Humboldt to Heinrich Christian Schumacher, Berlin, August 2, 1836, quoted in Karl Bruhns, ed., Life of Alexander von Humboldt. Compiled in Commemoration of the Centenary of His Birth, by J. Löwenberg, Robert Avé-Lallemant, and Alfred Dove, trans. Jane Lassell and Caroline Lassell (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1873), vol. 2, 56.

[2] Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, Essai sur la géographie des plantes (Paris: Chez Fr. Schoell, Libraire, Rue des Macons-Sorbonne, 1807), 22; translated in Humboldt and Bonpland, Essay on the Geography of Plants, ed. Stephen T. Jackson, trans. Sylvie Romanowski (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 69.

[3] Humboldt to Varnhagen von Ense, Berlin, October 27, 1834. Humboldt, Letters of Alexander von Humboldt, Written between the Years 1827 and 1858, to Varnhagen von Ense: Together with Extracts from Varnhagen’s Diaries, and Letters from Varnhagen and Others to Humboldt. Authorized translation from the German with explanatory notes and a full index (London: Trübner, 1860), 15-19. Quoted without ellipses in “Baron Humboldt’s Letters,” Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature 50, no. 2 (October 1860): 235.