Amidst the uproar that ensued after the incident at the Oscars ceremony last year, there were a few writers and reporters who wished to view it in a historical light. One of the ways in which they did so, was to point out that Chris Rock was actually exercising the age-old tradition of the “fool’s license.” This is the notion that fools and jesters of medieval and early modern times were licensed to speak freely in front of their employers, often being able to criticise their superiors without running the risk of retribution. It is commonly believed that this license was occasionally a result of the fool’s intellectual disability, which meant that what he said was not seen as anything to be taken seriously, even though it was also believed that fools could speak truths that no other man had access to.

This is an appealing image, and it is interesting to relate it to the Will Smith–Chris Rock encounter. Unfortunately, it is purely fiction, since the image we have of the historical fool is shaped by received notions from Shakespeare, Erasmus and other Renaissance writers rather than from the social reality of kept domestic fools. This is a shame, because if we actually go to the historical record on court and household fools, then we find an even more interesting, but also more complex, backdrop to the discussion on whether it is right or not to get angry at a comedian for making a joke.

Contrary to popular belief, there are numerous recorded instances of kings punishing their fools physically for going out of line. Perhaps the most famous example is of the fifteenth-century Duke of Ferrara sentencing his fool Gonnella to death after he pushed the Duke into the moat to cure him from an ailment. The ensuing execution was just a practical joke, and the Duke never intended to behead his beloved fool. The ruse was enough to terrify the fool, however, who promptly died from fright.

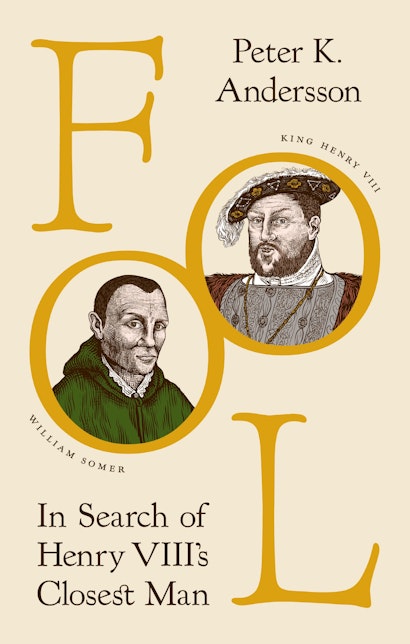

The wise monarch who soberly respects the agreement of a fool’s license to mock sounds more like a fairy-tale ideal than a person of flesh and blood. The image probably derives more from myth than from history. A helpful illustration might be Henry VIII. In July 1535, the imperial ambassador to Charles V of Spain writes in one of his letters that the king has “nearly murdered his own fool, a simple and innocent man, because he happened to speak well in his presence of the Queen and Princess, and called the concubine ‘ribaude’ and her daughter ‘bastard.’” Knowing Henry VIII, one can hardly be surprised at the king’s erratic behaviour and we know that he was prone to sudden outbursts. The parallel to the Oscars episode is of course difficult to ignore here, no matter how reluctant one might be to compare Will Smith to Henry VIII. A powerful man trying to uphold his dignity by “defending” the women in his life using his hands is a scene apparently as old as time. The ability to get offended only seems to grow in proportion to the offended potentate’s ego.

This particular incident seems to have been unusually violent, and there are not many records of kings physically assaulting or killing their fools. Rough treatment of fools was common enough, however, for the Tudor dramatist John Heywood to comment on it in his dramatic interlude Witty and Witless, written about the same time as Henry’s assault. At one point, one of the characters tries to prove how hard the life of a fool is by cataloguing the abuses they have to endure:

Some beat him, some bob him,

Some joll him, some job him,

Some tug him by the arse,

Some lug him by the ears,

Some spit at him, some spurn him,

Some toss him, some turn him,

Some snap him, some scratch him,

Some cramp him, some cratch him…

The list continues for quite a while until the character concludes that not even William Somer, the king’s own fool, escapes from time to time a good thrashing. Being fools, which more often than not meant people with some form of intellectual disability, it was sternly believed that they needed chastisement and discipline in the same way as children did. Physical punishment was as essential a part of Tudor upbringing and pedagogy, as of the keeping of a household fool. In this way the fool of the Renaissance might sometimes be more likened to a pet than to a comic entertainer.

The rough handling of fools was part and parcel of a type of conduct not uncommon at courts when the serious negotiations were over, and the courtiers indulged in a bit of horseplay. Another record from Henry’s court tells of how courtiers violently pushed a fool from his saddle, just for sport. When the Italian nobleman Baldassare Castiglione wrote his hugely influential Book of the Courtier, which was published in English in 1561, his aim was to purge the European courts of such rowdy and uncivilised conduct. He therefore saw fit to mention how courts now could do without such behaviour as pushing each other down stairs, causing each other’s horses to roll over, or throwing soup and gravy in people’s faces at dinner.

In this disruptive world, it is perhaps not surprising to find that the fools could also be quite violent themselves. There are records of a sixteenth-century provincial fool known as Lean Leanard who had a violent temper, repeatedly coming to blows with servants and villagers in consequence of their view of him as an open target to mockery. Of the aforementioned William Somer, it was also often mentioned that he, when scorned, would indiscriminately strike whoever was standing next to him instead of the person guilty of abusing him. It is then perhaps only natural that the fools who took to the stage as the Elizabethan playhouses proliferated were also infamous for getting back at their hecklers. The man who became the first legendary clown of the English stage, Richard Tarlton, had begun his career as a fool at the court of Elizabeth I. He was universally praised for his wit, but his sense of humour was more often than not cruel and bitter. When hecklers taunted him or threw apples at him, he was quick to retort with an anger that would nowadays induce an awkward silence but which then only made the crowds cheer even more. When Tarlton decided to trick a performing charlatan, he gave him a full piss-pot and asked him for a diagnosis based on its contents. When the quack said the patient would need treatment, Tarlton promptly drank the contents, which of course was not urine but wine. A decent joke, maybe, but the real punchline in the original version is one that would kill the humour today—he viciously threw the metal pot at his head. There is no information on whether the charlatan survived.

Notwithstanding the fact that we might find precursors to modern comedy in the early modern age, it cannot be denied that violence and cruelty has been an inherent part of comedy for much of human history. Let’s not forget that Tarlton and Shakespeare competed for audiences with bear-baiting and public executions. But what the examples I have given show when placed alongside modern-day examples is that comedy is always about a struggle for power, and one might find contemporary comedians who channel the same rage that Tarlton and Lean Leanard carried, albeit in a different manner. The stand-up comedian often bases his or her routine on rage and bitterness, but it needs to be strictly controlled in order not to make audiences uncomfortable.

Perhaps we are nowadays more used to seeing the indirect consequences of mockery in the enraged reactions of rulers and extremists. Here the link to the age of Henry VIII is apparent, and when it rears its ugly head today, one is reminded of that old sobriquet often applied to the clown in olden days—“He who gets slapped.”

Peter K. Andersson is senior lecturer in history at Örebro University in Sweden. He is the author of Streetlife in Late Victorian London and Silent History.