Four years ago, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the world, it brought with it an economic collapse. From March to May 2020, the U.S. economy declined more rapidly than in the Great Depression. More than 20 million people suddenly lost their jobs. Surprisingly, this economic devastation did not cause widespread suffering. Instead, financial well-being had actually increased by June 2020. Many people saved more as they stopped going out to eat or travel. Others benefited from unprecedented government aid to the unemployed, to nearly every small business, and direct deposits to most Americans.

The economy in the last four years is defined by the interactions between these two massive economic events: a sharp recession and improved financial security. A tsunami’s second and third waves are often its largest, as the complex contours of sea shelves and shorelines interact. And just like a tsunami, the pandemic’s later economic waves may also be its biggest and most important.

Financially healthy consumers created a better economy

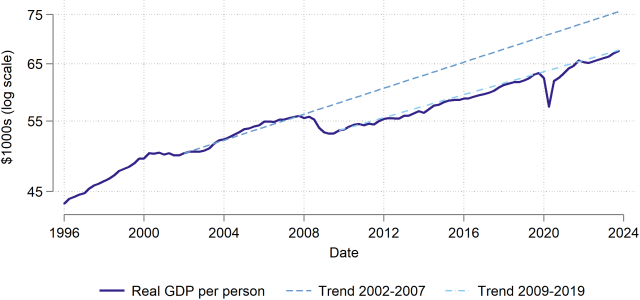

The biggest pandemic economic surprise was how quickly the economic collapse disappeared. By the end of 2023, real U.S. GDP per person was back to where it would have been if the pandemic had never happened and the economy had just kept growing the way it had in the previous 10 years (see Figure 1). Employment, the broadest measure of economic success, was higher in 2023 than 2019. By 2023, it was as if the pandemic hadn’t happened, macro-economically speaking.

The pandemic economic experience was unique in recent history. The US never recovered from the Great Recession, which permanently lowered GDP per person. Employment had only just reached its 2007 high by 2019, marking a decade of wasted potential and financial distress. The continuing economic cost of this failure is around $28 trillion.[1] In addition, the U.S. appears to be an outlier in how well it weathered the pandemic, with many Europe nations still below their pre-pandemic GDP per person and far below their pre-pandemic trends.

The U.S. pandemic experience is different because robust U.S. financial aid improved the financial situation of almost all Americans. The last several years of growth are largely explained by consumers with lower debts and more savings being willing to spend. That robust spending created demand for goods and services, encouraging employers to hire and produce, and creating a strong recovery, despite the pandemic economic dislocations.

Moreover, improved household financial health helped create a better economy for most people. Financially secure people were more willing to push their employers for better jobs and more pay, switch jobs when opportunities arose, and strike, all of which have helped wages increase more rapidly than inflation, especially at the bottom end. Financially healthy people started new businesses with nearly 50 percent more new business registrations in 2023 than in 2019 which may lead to more rapid economic growth.

Having erased the 2020 pandemic economic collapse, we aren’t just returning to the economy in 2019. Instead, the economy in early 2024 is better for most people. That’s a remarkable success for policy.

Compared to the Great Recession or other advanced economies’ post-pandemic experience, the $5 trillion spent on pandemic relief looks like a great investment, paying for itself several times over. To put that money in perspective, $5 trillion is about two years of the lost output from the Great Recession. Of course, not all of that money was spent well, a topic I cover in my book on the pandemic economy, The Pandemic Paradox: How the COVID Crises Made Americans More Financially Secure, but that just means the return on investment could have been even better.

Inflation was just a pandemic wave, retreating rapidly

The post-pandemic economic wave that caught the most attention was inflation. Standard introductory economics describes how prices are the way that market economies signal what is in demand. High prices convince producers and retailers to make more of something available. What is often left out is how messy the signaling process is. Normally, the messiness doesn’t matter much, but the pandemic caused such rapid changes that suppliers were always behind, first underproducing (Pelotons, masks) then overproducing (Pelotons, masks).

Higher prices are the signal to make more of something, but supply constraints, from transportation to available labor, meant that it took time to get the goods or services to market. In the meantime, higher prices convinced some people to wait or buy something else. Other unrelated supply issues, such as the Avian flu that doubled egg prices and Russia’s Ukraine invasion that increased energy prices sharply, helped spread price increases more broadly, leading to a brief period of high inflation that peaked in 2022 then retreated rapidly. While there is surely more nuance, the basic story is of supply catching up with demand.

Financially healthy consumers with money to spend surely contributed to some of the inflation by increasing demand. But inflation was high in other countries where pandemic aid was more limited, suggesting that supply difficulties were vastly more important. And those financially healthy consumers are the reason the rest of the economy was doing so well.

People hate inflation because it causes them to have to think about how much things cost and sometimes make different choices—such as to drive less or buy fewer eggs—which is just textbook economics at work. And price increases are hard for some people (low-income renters), even while they benefit others (landlords). But with wages mostly keeping up with inflation, for most people the economic costs of a brief high inflation period were minor compared to what the real costs would have been if the economy had not recovered well. In a real-world trolley problem, who would you choose to lose their job, so you don’t have to think about the price of eggs?

Many seem to have reached the conclusion that post-pandemic inflation means pandemic policies were a mistake. They are wrong. First, because pandemic relief policies contributed only a small amount to that inflation. Second, because, as the lost output from the Great Recession illustrates, an incomplete recovery’s costs are massive compared to the small costs from a brief period of inflation.

The third wave: Remote work and rising housing costs

The share of days worked remotely stabilized in late 2022 at about 28 percent and hasn’t budged since. While it’s possible a recession might shift things a bit, remote work appears here to stay and marks a remarkable transformation in work flexibility.

Despite reactionary executives in business and government, remote work “is a win-win-win, benefiting employees, firms and society” to quote Nick Bloom, a leading economic researcher on remote work. As more research comes in, the evidence is solidifying that remote work is about as productive as in-person, depending on the task. But productivity is measured in working hours and ignores the massive personal, social, and environmental cost of commuting. Remote work would have to be much less productive to make up for the time wasted commuting.

Beyond the time saved commuting, remote work’s flexibility has also been crucial to female labor force participation and to bringing people with disabilities—but lots to offer—into the labor force. Businesses benefit from maintaining smaller offices and by giving their employees something they value. At the same time, we don’t yet know how remote work will affect training and career development.

Hybrid workers still need to come into the office occasionally, limiting how far away they can move, but truly remote work offers more revolutionary possibilities: of fully distributed companies with no true central nexus; of the ability to hire the best person from a national market; and of the ability to live anywhere. These shifts offer the possibilities of better lifestyles, higher economic growth, and revitalized hinterlands.

About 13 percent of workers are fully remote, which is hardly a revolution yet. Yet new firms are more likely to be fully remote. After all, worker demand for remote work is much higher than the supply, so if you are starting a new company, allowing remote work lets you hire more easily from a bigger pool, not pay Silicon Valley or New York City office rents, and be able to expand more quickly. In a dynamic economy, these new startups will compete and grow and, if they are more effective, surpass their predecessors. Thus, while the brief pandemic experiment in fully remote work hasn’t yet created a revolution, perhaps it has opened the door for one.

Remote work did create a massive new demand for more housing as people shifted from downtown offices to home offices. As a result, house prices increased and stayed high despite high interest rates, and rents rose faster than inflation in 2021 and 2022. Much of measured inflation in 2023 came from these price increases gradually making their way into official measures.

Housing drives almost every other decision people make. Where should I work and live (what can I afford)? Should I get married and have kids (can I afford to house them)? Can I afford this medical bill (not if half of my income goes to rent)? From Texas’s population boom, to financial distress, to evictions, to population growth, housing costs are the monster looming behind most of our biggest long-term changes and challenges. And that monster is getting bigger.

Pandemic policies ended, but their impact continues

Four years after the pandemic, the economy is the best it’s been in decades, yet it still leaves too many people out. During the pandemic, aid policies and reduced spending improved financial health for most Americans. Some of these policies were pandemic specific, but others—such as allowing greater eligibility for unemployment insurance or a refundable child tax credit—could have continued.

As they ended, these policies’ effects were easy to observe. When the American Rescue Plan Acts’s refundable child tax credit ended, child poverty nearly doubled. While there have been efforts to improve many states’ unacceptably bad unemployment insurance administration, the pandemic unemployment expansion that brought benefits to many more people ended as well. Now, only one quarter of unemployed receive unemployment insurance benefits.

While the new industrial policies might not have happened without the pandemic, the pandemic policies to help people directly have mostly withered. In his review of The Pandemic Paradox in The New York Review of Books, Matthew Desmond asked: “How could we have allowed the relief programs to disappear?”

Desmond suggests it’s because we didn’t advocate for them. And, distracted by inflation, we didn’t, but maybe it is just too soon. Bills have been introduced to revive the refundable tax credit and improve unemployment insurance although without a crisis to sharpen attention, their future is uncertain.

Instead of government policies, the pandemic’s biggest wave may be the underlying shift in power towards labor which started in 2021 and 2022 but expanded in 2023. The most visible evidence is a string of union wins in the auto industry, at UPS, and in Hollywood, although private sector unions remain small. More broadly, low unemployment means more people are earning wages and the tight labor market has sharply decreased wage inequality. If it continues, this shift will be more gradual than direct policies but may reshape the U.S. economy in even more profound ways as people individually and together seek to improve their lives directly.

The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of the CFPB or the United States.

Scott Fulford is a senior economist at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. He has a PhD in economics from Princeton University and he taught economic and international studies at Boston College before joining the CFPB. His academic and policy research examines the economic problems individuals and households face and how they use financial products to help deal with them. He lives in Washington, DC, with his wife and two young children.

Notes

[1] While counterfactuals are always tricky, $28 trillion is the total in 2023 dollars of lost GDP output comparing actual GDP to GDP if the economy had continued its 2002-2007 growth path as shown in the figure.