As a philosopher who writes about love, I am sometimes asked what I love. I could answer in particulars: specific people, places, and objects. But in a more general way I suppose that what I love, perhaps above all else, is being fascinated. I think all the time about those works of art that have fascinated me, captivated me, held me spellbound. Some of them I plan, or hope, to experience again. Some of them are elsewhere, distant, inaccessible. I might never re-encounter them. I have only my memories to rely on. And then there are the others, the artworks I have been fascinated by even though I have never, in fact, been able to experience them, and never will. There is something quite fascinating, I suppose, about the fact that this is even possible. Even more, that their power to fascinate is not only undiminished by the absence of an actual encounter, but in many cases intensified by that absence. Having never come into contact with them, I can never outgrow them or become bored of them. They will haunt me forever. Or at any rate, that is how it feels.

Andre Gregory’s production of Alice in Wonderland, performed by his theater company, The Manhattan Project, in the early 1970s, haunts me, disturbs me, obsesses me more than almost any work I have actually seen performed. I return to it again and again in my thoughts, wondering about its meanings, imagining that I am there, trying to picture what it must have been like. As one would expect of a theatrical work produced a half century ago, it has left few traces little of it remains. There are written descriptions: reviews and recollections, memoirs by people involved in it. A few recorded fragments, just enough to be tantalizing. I am glad, to be honest, that there aren’t more of those. A recording of a theatrical work can never do more than hint at the experience of actually seeing a live performance. It’s better for me, and for the attachment and affection I feel for this particular piece, not to be fooled into believing otherwise. Those who saw Alice in Wonderland speak of it as a unique and incomparable spectacle, a life-changing event. In the private theater of my imagination, that is precisely what it is.

Perhaps that is what I love most about theater, and indeed all live performance. The fact that, rather than deny ephemerality, such art proceeds by embracing it. The promise of art to encapsulate and preserve what matters most to us is an enticing promise but ultimately a false one. Given enough time, everything disintegrates. Live performance makes glorious that process of disintegration, transmuting it into intensity and beauty. We are aware that what we are seeing is singular and can never really be repeated, and every astonishment, every fascination, every moment of pleasure we feel while experiencing such art contains a melancholic core, an acknowledgment of mortality and finitude.

Of course, artists working in other media can do this, too. Think of the delicate constructions of Andy Goldsworthy, composed of ice, of powder tossed into the wind, of leaves on water. Many of these works, by design, vanished before anyone but their creator could see them. All we have is the photographic evidence; that, and our imaginings. And works intended to endure can also fail to do so—will also fail to do so, inevitably, given enough time. How often have I dreamed of being able to read the lost plays of Aeschylus. Or of being able to sit in a theater and watch the original version of Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, whose legendary ending was dumped in the ocean after the studio insisted that it be replaced with a more conventional and banal resolution.

Heard melodies are sweet, writes Keats in “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” but those unheard are sweeter. The statement is meant to strike us as a bit paradoxical: the idea of an ‘unheard melody’ isn’t an oxymoron, exactly, but it’s in the ballpark. And yet, what Keats says is true: our enjoyment of the beauties of this world is so frequently tinged with an imagining of the even more perfect beauties one might find in a less flawed world—or in this one, if only this world could be somehow improved, purified of its corruptions.

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone…

Keats’ poem, of course, is addressed to an enduring artwork, an urn that depicts a bucolic scene, and the melodies he refers to are those played by the musicians depicted in the scene—which, since the musicians are frozen in time, explains why they are unheard. Music is motion; stilled, it relapses into silence. His ode recognizes art’s ambitions to freeze and preserve life even while forcing us to recognize that such preservation, on the level of metaphor, amounts to a kind of death: the “bold lover” of the poem may be freed from grief, as his lover will never age and die—and nor will he—but, precisely because they are not alive, they can never consummate their passion with a kiss, but are instead condemned to remain forever on the verge of one.

The profound and beautiful works that I have missed, in one way or another—either because their existences intersected with the lives of others but not with mine, or because they never existed at all or if they did, only barely—are, for me, unheard melodies, played by the soft pipes, sensed by spiritual and not sensual ears. Ethereal, existing apart from existence, they can only be imagined as perfect, though I can never actually touch them. In a poem wryly titled “Envy of Other People’s Poems,” Robert Hass spins a variation on the fable of Odysseus and the sirens, in which the sirens could not actually sing—their legendary singing abilities were purely mythical—so that Odyssues ends up “harrowed / By a music that he didn’t hear,” and the sirens themselves,

Seeing him strain against the cordage, seeing

The awful longing in his eyes, are changed forever

On their rocky waste of island by their imagination

Of his imagination of the song they didn’t sing.

I have thought about this poem, about this image, many times over the past eighteen months. Months during which so many theaters and concert halls and auditoriums have been silent and dark, so many instruments untouched. There is no way to count the performances that have gone unperformed, the unsung songs and unheard melodies that haunt these spaces like ghosts. But perhaps it really is possible to be moved, changed forever, by a song that is not sung. Or by our imagination of it. Or by our imagination of someone’s imagination of it.

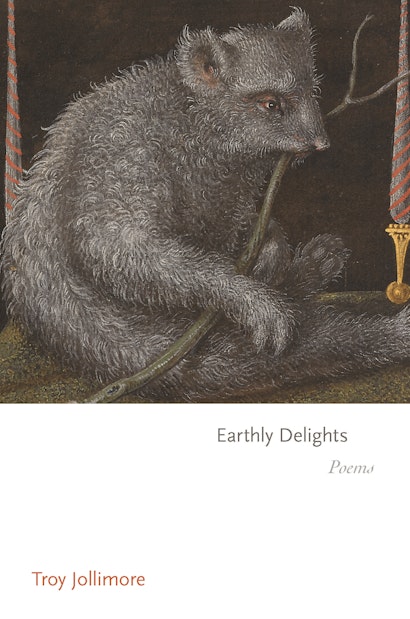

Troy Jollimore is the author of three previous collections of poetry: Tom Thomson in Purgatory, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award; Syllabus of Errors (Princeton), which was chosen by the New York Times as one of the ten best poetry books of the year; and At Lake Scugog (Princeton). His poems have appeared in the New Yorker, Best American Poetry, McSweeney’s, and many other publications. He is professor of philosophy at California State University, Chico. Website www.troyjollimore.com Twitter @TroyJollimore