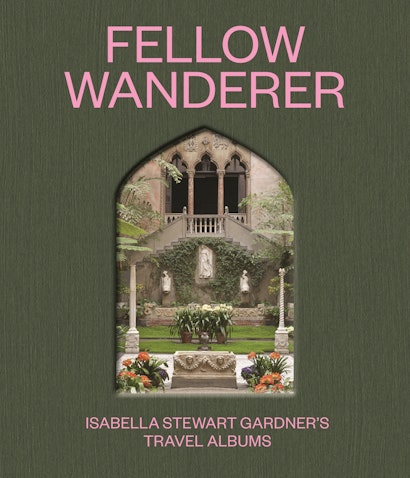

Entering the historic building of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston’s gray skies and chaotic traffic fade into memory, replaced by the sounds of bubbling fountains and the humid scent of the garden flowering at the heart of the museum (fig. 1). The striking contrast between the museum’s dun-colored exterior and its transportive interior heightens visitors’ sense of having traveled a great distance by merely crossing a threshold. To describe the fairy-tale effect of the Gardner’s spellbinding interior is to verge upon the cliché—and yet, the historical bridge between its enchanting atmosphere and the global travels of the museum’s founder and namesake is a complicated one that needs restoration. Some of the most vital documents compiled by the legendary art collector and museum founder Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924)—extraordinary photographic travel albums that she assembled between 1867 and 1897—help us do just that (fig. 2).

Although many wealthy Americans traveled internationally in the nineteenth century, Gardner traveled more—and to more far-flung places—than most women of her era and status. After the death of their two-year-old son (and only child), Isabella (fig. 3) and her husband Jack Gardner planned an extensive itinerary through Northern Europe to begin healing from their loss. In 1867, the pair sailed across the Atlantic to embark upon a journey throughout Scandinavia and parts of the Russian Empire. The trip had a restorative effect, and Gardner returned to the United States a changed woman.

This journey inspired the couple to take many elaborate trips over the next three decades. They visited approximately thirty-nine countries (using twenty-first-century borders) across Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and North America, often on months-long itineraries. Gardner was an intrepid traveler who moved by train, steamer, sailboat, as well as her own feet—and occasionally on the back of a mule or elephant. Far from idle in her staterooms and coaches, she created over two dozen original compendia to remember these voyages.

Her activities were not necessarily unusual: many wealthy American travelers in the nineteenth century compiled similar volumes to serve as memory aids, didactic showcases, and family records. Still, Gardner devoted significant energy to the collection, creation, arrangement, and display of photographic documents throughout her life, producing a broad range of photographic books over the course of her eighty-four years. These compendia provide unparalleled insight into the mind of the woman who would become one of the Gilded Age’s most celebrated—and misunderstood—civic innovators.

Today, the collection of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum includes twenty-eight photographic travel albums compiled by its founder. They contain a range of landscape and ethnographic photographs from the nineteenth-century tourist trade, as well as photographic reproductions of art and architecture. The albums also incorporate a striking variety of materials beyond photographic documents, including watercolors, handwritten captions, news clippings, botanical samples, and travel souvenirs.

For reasons that have been lost to the historical record, Gardner was deliberately opaque about her curatorial and design strategies for Fenway Court, the name given to the museum during her lifetime. Near the end of her life, she even destroyed much of her personal correspondence. Her albums represent the most important compilation of source material for the museum. Assembled in concert with her traveling, they represent her immediate responses to a range of world cultures, whose artworks and objects she would eventually display in her eponymous art institution. They also serve as material evidence of the evolution of her design strategies for the same: a distinctively layered, syncretic architectural environment composed of elements—both live and inanimate—drawn from across the globe. The albums tell a more complex story than has often been told about her engagement with foreign cultures.

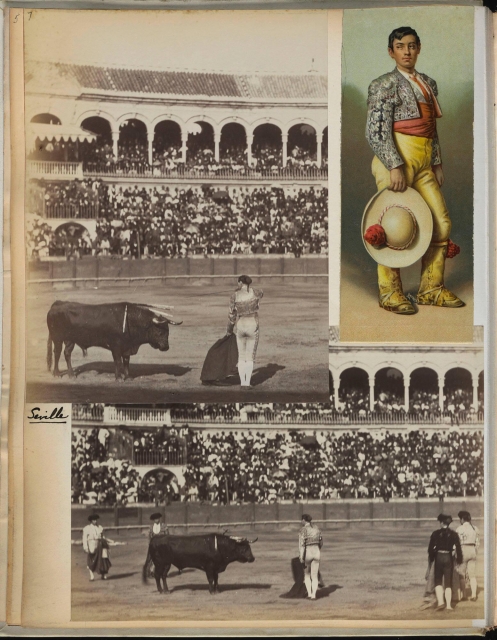

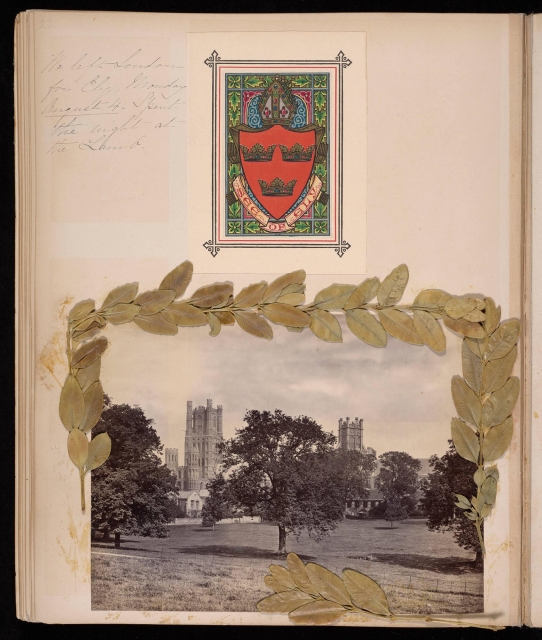

For much of the Gardner Museum’s history, Italy has been identified as the primary source for the foreign atmosphere often attributed to it. Isabella’s passion for Italian cities and people, the art and literature of the Italian Renaissance, and her decision to live for several months at a time in the Palazzo Barbaro on Venice’s Grand Canal (fig. 4) have been well-documented. Though Italy was inarguably a potent force for Isabella, her photo albums illuminate a more worldly cultural perspective and set of interests. When taken together, these painstakingly created volumes reveal the breadth of her aesthetic and intellectual engagement with the world: its people, architecture, plant life, traditions, faiths, and more. Of the twenty-eight travel albums she produced, six are dedicated to her trip around Asia from 1883 to 1884; two are focused on the Middle East; Spain receives two volumes. Her 1879 British albums were formative to the development of her collage-making practices (fig. 5). It is also evident from the albums that Isabella cultivated sincere respect for and a passionate interest in the places she visited.

Isabella’s global journeys shaped the character of her vision and the goals underpinning her synesthetic curatorial regime. One may see this most clearly in the design of her museum’s courtyard, the light-filled space around which her institution revolves. With its distinctively blush-colored stucco walls and windows taken directly from the façade of a Venetian palazzo—the Ca d’Oro—the space at first appears to be a relatively straightforward transposition of Venice into Boston. Her travel albums, however, provide grounds for an alternative interpretation.

Gardner visited Venice for the first time as an adult, after a year-long trip through East, Southeast, and South Asia. Rather than entering the city from Northern Europe, as many wealthy American travelers did, Isabella came to Venice by way of India—where she had spent three months touring a vast range of cities and sites seen by few of her acquaintances. The two albums Isabella produced of India devote a great deal of attention to architecture (fig. 6). She selected photographs of a courtyard in Northern India that, upon further reflection, bears a striking resemblance to the museum’s central Courtyard. Moreover, the choice of pink for the Courtyard’s wall color—something typically linked exclusively to the Palazzo Barbaro—can also be understood in an Indian context. Isabella traveled to Jaipur, where the buildings have been painted pink routinely since 1877. None of the above is meant to deny the broader influence of European sources, especially those in Italy, upon the collection and design of the Gardner Museum. Rather, it is to restore the institution—and the far-ranging intellectual and civic intentions of its founder—to a network of global influences and her view of it as an homage to the cultures she knew she was privileged to visit.

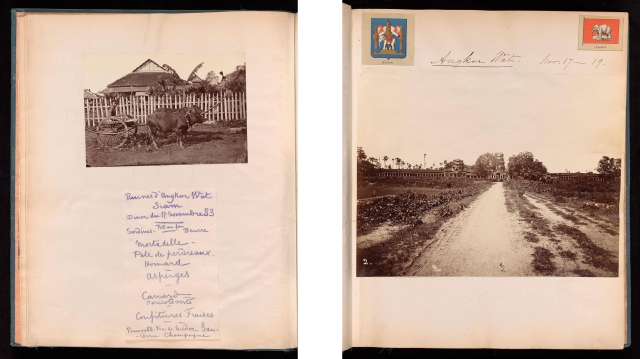

At the same time, Gardner’s travel albums cannot be separated from the complexities of her social and political position. Despite historical reports of her respectful interactions with the foreign cultures and people, Isabella’s voyages were facilitated by extractive and repressive colonial enterprises, particularly in Asia. Consider the album pages in which she introduces Angkor Wat, the exceptional temple complex in Cambodia. It seems that few Americans visited the complex in the late nineteenth century. How had she come to travel there? Through a chance meeting with two French colonial who facilitated their visit. These colonial links are evident in a spread that juxtaposes a photograph of the road to Angkor alongside an elaborate menu handwritten in French (fig. 7). The title above the menu suggests that the Gardners enjoyed a multicourse French meal amid the ruins of the temple complex—a fitting metaphor for the all-consuming appetites and ravages of colonial power.

These scenes cannot and should not be extricated from any reading of Isabella’s albums, as they also reflect the mindset and perquisites of their creator. The collection and remixing of material objects from diverse cultures is, at its heart, a colonial enterprise. Displaying the works she purchased around the world in a Boston museum—thousands of miles away from the contexts in which each was created—represents a form of violence in its displacement of objects from the people who cherished them. The idiosyncrasies of her signature arrangements of objects from disparate cultures and eras can sometimes further distance these artworks from their cultural origins. As scholars of Gardner and her era, we aim to balance appreciation and exploitation as uneasy partners in the complex creative dynamic that fueled this legendary founder and her exceptional museum.

Diana Seave Greenwald is assistant curator of the collection at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Her books include (with Nathaniel Silver) Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life (Princeton).

Casey Riley is chair of global contemporary art and curator of photography and new media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. She is the author (with Christina Nielsen and Nathaniel Silver) of Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: A Guide.