We know that words wield immense power. They express, represent, inspire, provoke, evoke. They can wound, figuratively, and also literally. And in the emergence of generative artificial intelligence applications such as ChatGPT, we’re grappling with the fact that the words we encounter might originate from sources other than human beings. Or any beings at all.

We only have to pay attention to the headlines to recognize that words are ground zero for the collision of perspectives over issues ranging from protected speech to gender expression.

And that is exactly why I want to talk about poets.

Like many of us, poets trade in words. But their work is not on behalf of would-be “certainties” or convincing arguments; it’s on behalf of the ambiguities—and the meaning-making enabled when we’re courageous enough to dwell in grey spaces. Poets are an excellent source of intelligence when we want fresh insights into what’s at stake when we wrangle with words.

To bring this into focus, let me ask: what do a couple of Victorian lady poets have to teach us about the generative intelligence of language?

A great deal, it turns out.

First things first. Because words matter, I should be more precise in the terms I use to describe this pair. They were both gifted poets in their own right, and they were both women. I took a liberty in describing them as “lady poets,” however strictly accurate that characterization.

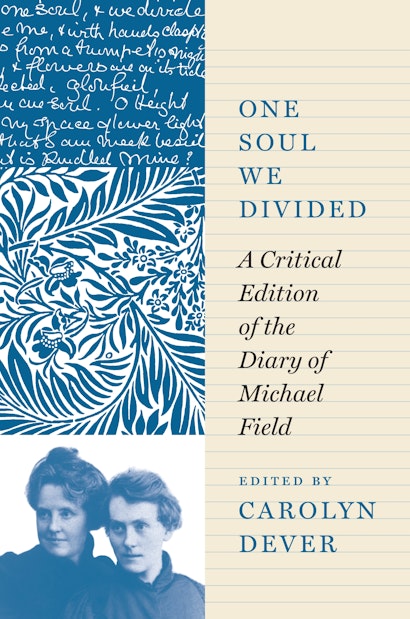

For in fact, these two women, Katharine Harris Bradley (1846-1914) and Edith Emma Cooper (1862-1913), existed in the literary world as one poet, not two. And as a man, not as women. Under the name “Michael Field,” Bradley and Cooper published eight volumes of poetry and twenty-seven verse plays. They also wrote a boundary-crushing shared diary, a tour de force of experimental private writing, over the span of thirty years.

In public, Michael Field appears as the author of Michael Field’s published works. But even throughout their private diary, we see the two poets approaching “Michael Field” playfully. They speak of him frequently, and they occasionally speak as him. They further distribute his singular male identity across their double female ones: “Michael” and “Mick” were nicknames for Bradley; Cooper was by turns “Field,” “Henry,” and “Henny.” Michael Field was a vehicle for the public circulation of late-Victorian poetry. He was also a vehicle for private communion between his two constituent women.

Through the figure of Michael Field, Bradley and Cooper conducted a longitudinal experiment with at least two foundational elements of the English language: with gendered pronouns, by turning their she’s into he’s; and with grammatical number, or the distinctions between singular and plural that govern how nouns, pronouns, verbs, and adjectives typically keep company. “We must remember we are Michael Field,” Cooper writes in the double diary in 1888.[1] Plural pronoun and verb; singular object. Watch the experiment unfold.

Because Michael Field are a poet (singular proper name, plural verb, singular object), their ongoing linguistic experiment seems deliberate, even calculated. While explaining the nature of their collaboration in a letter to the poet Robert Browning in 1889, for example, Edith Cooper wrote, “This happy union of two in work and aspiration is sheltered and expressed by ‘Michael Field.’”[2] For Cooper “Michael Field” is a signifier of “happy union,” consecrated in work, in aspiration. To take the concept of happy union one step further, Bradley and Cooper were longtime lovers who often wrote of their relationship as a marriage. In that sense, when we think of “Michael Field” as their married name (uniting two into one), we can see Michael Field slyly appropriating the doctrine of coverture on behalf of their queer-poetic identities.

William Blackstone described the effects of coverture on women: “By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs everything; […] her condition during her marriage is called her coverture.”[3]

In Blackstone’s rubric, two separate subjects marry. The marriage causes the union of the two into a single, unified—and male—person: bride + groom = husband. In the case of Michael Field, Bradley + Cooper = Michael Field.

Through the efforts of Victorian feminists, the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882 had mitigated the legal standard of coverture by the time Michael Field took to the page, consistent with a wave of legislative reforms that extended legal personhood in new directions, including those of gender, race, and property ownership.

But where a legal standard may lead, cultural standards lag. Consider again Michael Field’s experiment in appropriating a traditional patriarchal form of heterosexual marriage on behalf of their queer poetic union (of voices, of bodies, of identities). Here we see Michael Field sampling the effects of the patriarchal conscription of married women under a male legal subjectivity. They redeploy this trope on behalf of two living women—femmes seules, in the eyes of the law—and an imaginary male poet.

The fact of Michael Field’s “true” identities was one of the worst-kept secrets of the fin de siècle. In 1889, Browning traded in a bit of gossip about the “young man” who was taking the world of poetry by storm with a volume of Sapphic lyrics titled Long Ago. Even after Browning let the cat out of the bag, though, Bradley and Cooper continued to use the Michael Field pseudonym until the ends of their lives. It seems fair to consider this, at least in part, as shade: demonstrating the failed erasure of female subjects behind the public face of a man.

And to quote the Bard, “Shade never made anybody less gay.”[4]

The complicated case of Michael Field spotlights the idiosyncracies of pronoun and number in the English language. We’re familiar with the “Royal ‘we,’” which allows one person to claim the plural pronoun to indicate that she or he also represents a high office. My college-age self found the universal male pronoun to be an outrage of misogyny and imprecision; my medieval studies professor was reciprocally horrified when I applied a universal female pronoun to his British colleagues who published Chaucer criticism using their first initials. Turnabout, I soon learned, is not fair play.

When Michael Field appropriate male pronouns on Michael Field’s behalf, they’re operating within—and pushing against—the guardrails of linguistic conventions of the moment. Further still, when they, as women, appropriate the grammatical conventions of number, they highlight the insidiously easy erasure of women in heterosexual marriage and in the legal personhood that follows. Michael Field pull back the curtain, or open the kimono, or drop the trousers—choose your metaphor—to reveal the queer lives lived under cover of a man’s name.

Notes

[1] Michael Field, One Soul We Divided: A Critical Edition of the Diary of Michael Field. Carolyn Dever, ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024, 35.

[2] Quoted in Emma Donoghue, We Are Michael Field. Bath: Absolute Press, 1998, p. 39.

[3] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1874). London: Oxford. Vol. I, p. 442.

[4] Taylor Swift, “You Need to Calm Down.” Lover. Republic Records, 2019.

Carolyn Dever is professor of English and creative writing at Dartmouth College. Her books include Chains of Love and Beauty: The Diary of Michael Field (Princeton) and Death and the Mother from Dickens to Freud: Victorian Fiction and the Anxiety of Origins.