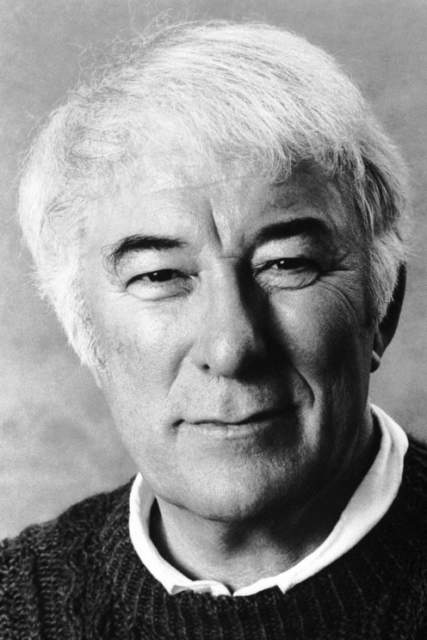

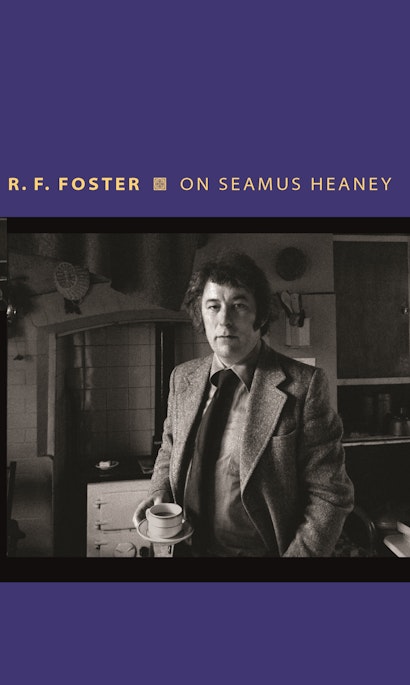

The most important Irish poet of the postwar era, Seamus Heaney rose to prominence as his native Northern Ireland descended into sectarian violence. A national figure at a time when nationality was deeply contested, Heaney also won international acclaim, culminating in the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995. In On Seamus Heaney, leading Irish historian and literary critic R. F. Foster gives an incisive and eloquent account of the poet and his work against the background of a changing Ireland.

Why is a historian writing about poetry, and why about Seamus Heaney in particular?

RF: Besides making the obvious point that you don’t have to have a degree in English Literature to read, enjoy and discuss poetry, I’ve spent many years studying the work and life of W.B.Yeats (I wrote the two-volume authorized life, which took eighteen years of total immersion, besides shorter books and essays dealing with the poet). Irish history is intertwined with the creation of world-class literature, and the historical expression of Irish identity is closely related to literary history; in fact, the history of Irish national identity (a larger subject than Irish nationalism, though closely connected with it) can be tracked and profiled through the work of writers such as Jonathan Swift, Thomas Moore, Maria Edgeworth, James Joyce, Flann O’Brien, Elizabeth Bowen… and above all, Yeats. Heaney is squarely in this progression, and much of his poetry and prose is devoted to unscrambling the complicated business of Irishness. He viewed it from the peculiar vantage of Northern Ireland, where he grew up and lived through a period of shockingly violent confrontation, before moving to live in the Republic of Ireland in 1972. The way he processed and reflected the underlying and overt antagonisms of the Northern situation fascinates me, as does the position he came to occupy in Irish life. He was a figure of immense and benign authority who managed nonetheless to preserve a creative independence and—to a certain extent—evasiveness: a central theme in my book. There’s also a very obvious answer to this question, which is that his poetry ‘speaks’ to me, and always has. I remember where I was sitting when I read North and the hairs stood up on my head, I remember the impact of individual poems which I cut out of newspapers or magazines over nearly fifty years, and I was immensely moved by his very last collection about death and loss, Human Chain. I’m not alone. His ability to strike a chord with a very wide readership fascinates me, and I wanted to try and show how this was created and sustained.

Is there a connection back to Yeats, and is that a theme in this book?

RF: Heaney said that Yeats uniquely ‘achieved authority within a culture’, and I think the same thing could be said of himself. At the same time, he was very careful to avoid simplistic comparisons with his great predecessor, which cropped up in reviews of his work from the publication of North (1975) onward, and were reinforced when he (like Yeats) won the Nobel prize, in 1995. A striking early essay is called “Yeats as an Example?” and we should note the question mark. But like Yeats, Heaney was a public figure, and like Yeats, his work tackled and interrogated central themes in Irish history head-on, notably the inheritance of colonization, violence, hatred—as well as the cautious possibilities of reconciliation. His play The Cure at Troy is a celebrated example, much used and abused by politicians. My approach to Heaney does recur—inevitably—to Yeats, more and more as his life and work develops; that question-mark about Yeats being exemplary is implicitly dropped. Particularly, it’s the Yeats of ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, a poem which Heaney put at the centre of his Nobel acceptance speech; and, I argue, the later Yeatsian poetry of visionary Heaney certainly didn’t, but in the later volumes there’s a very Yeatsian sense of transcendence (reflected in titles like Seeing Things and The Spirit Level). From early on, his poetry summons ghosts. Also, like Yeats, he wasn’t afraid to be controversial, an aspect I’ve paid a certain amount of attention to; and the reactions to his poetry were often rooted in politics as much as aesthetics.

So, how ‘political’ a poet is Heaney?

RF: I think that a writer born in rural Ulster in 1939, attending university in Belfast, and living and working in that city through the 1960s and early 1970s, couldn’t be other than political. Religion and politics are intertwined in Northern Ireland, and Heaney’s Irish Catholic conditioning is a vital part of his artistic vision, as he himself said more than once. This remained true despite his moving to a non-practicing stance fairly early in life, his notably internationalist perspective, living and teaching in the USA for long periods, and the fact that he was very much at home in British literary life. His background, and the continuing violence in Northern Ireland, exerted a certain pressure to take a political stance, and my book shows that some of his early poems (and notably some unpublished work) does so quite unequivocally. His long poem ‘Station Island’ is an interrogation of the intellectual and political world of Northern Catholicism, and forms the ‘hinge’ of my book. But another powerful theme in ‘Station Island’, as in North, is the tension between articulating the voice and concerns of his ‘tribe’—and the necessity to preserve an independent poetic voice (the ghost of Joyce is unforgettably summoned up as an exemplar at the end of Station Island). What astonishes and impresses me about Heaney is the way in which he kept his integrity, articulated the sense of crushing injustice under which Catholics had historically laboured, recognized the savagery that came from years of antagonism—and at the same time illuminated a hopeful humanism, without ever taking refuge in sentimentality or wishful thinking.

Is the influence of writers in Irish life, and the response to them, notably different in Ireland compared to Britain, and how does Heaney’s life illustrate this?

I think in Ireland, as in France, or Poland, or several other European countries, writers occupy a more recognized space, and exert a stronger authority, than in Britain. England possesses the institution of a Poet Laureate, but creative writers in Britain have never occupied the ‘national’ position of, say, Sartre and Aron in France, or Milosz in Poland, or Pushkin in Russia. This remains the case in contemporary Ireland; for all the dumbing-down of culture, writers such as Colm Tóibín, Sebastian Barry, Roddy Doyle, Edna O’Brien and Anne Enright are recognized, listened to, and taken pride in—on a national level. Both Enright and Barry have been high-profile Irish Laureates for Fiction, and there’s the institution of ‘One City, One Book’, whereby a book connected with Dublin is nominated annually in April, and celebrated by readings and other events connected with it. Not to mention the celebration of ‘Bloomsday’ on 16 June every year, in honour of Joyce and Ulysses. You might fairly say that this contrasts markedly with the way Ireland treated Joyce in his lifetime, but it’s a different country now, and living writers are hailed with honour in their own country. Edna O’Brien is one writer whose life and reception has charted this change.

All these examples are fiction writers, and poetry may seem to occupy a less high-profile position, but the last half-century has seen an extraordinary constellation of celebrated poets, especially in Northern Ireland—Michael Longley, Derek Mahon, Paul Muldoon, Ciaran Carson, Tom Paulin. Heaney is the supreme example and his impact has been immense. His poetry, as I’ve already said, ‘spoke’ to a large and varied readership, far transcending the usual audience. This was partly because of the way he preserved and memorialized a forgotten rural past, in language that unerringly pinpointed and made concrete the practice of farming before ‘agribusiness’. He unerringly summoned up the sights, tastes, smells, sensations of life in the Irish countryside as many of his readers had known it, but which had disappeared by the later twentieth century. But there was far more to it than that. His poetry also articulated, with uncompromising perceptiveness, the concerns and dilemmas presented by the inheritance of antagonism in Irish life—famously though the extraordinary and chilling metaphor of artifacts and bodies preserved in bogland. Reading him brought a sense not only of revelation, but of confirmation. “Yes,” people thought, “that is how it is, and that is what it is like.” And that clarification conferred a kind of liberation. His readers trusted him, with good reason. The conclusion to my book discusses this phenomenon, and the reasons for the unparalleled public reaction in Ireland to his death. I suppose my book is an examination of how one extraordinary writer’s life was embedded in the historical context of his times, and made a difference to them. It’s also a portrait of a unique individual, through his work as well as his life. He’s a wonderful subject and through writing about him I feel I’ve got to know him better. I hope my book makes readers feel that too.

R. F. Foster is Professor of Irish History and Literature at Queen Mary University of London and Emeritus Professor of Irish History at the University of Oxford. His many books include Modern Ireland: 1600–1972, the two-volume W. B. Yeats: A Life, and, most recently, Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890–1923. Foster’s writing has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Review of Books, the Irish Times, and many other publications. He lives in London.