I thought it was gone. I thought it had left me or I had left it somewhere in the street, in a cabinet, inside the grocery store, at the gas station. The arguments were depleting, had become idiotic, fantasy. Weariness had taken me. Had taken many of us. During this COVID-19 pandemic, I have the daily habit of walking to my neighborhood park to watch the sunset. With headphones over my ears and a mask over my mouth and nose, I listen to Charles Mingus’ “Self-Portrait in Three Colors”. There, from a bench, I watch the sky blush as the sun’s powerful glare sinks into the White Mountains of New Hampshire. I then walk home, the same song in my ears. The same breeze over my face. The same fears: virus and violence.

Hope didn’t exist for me. I couldn’t see or sense it. Everything was telling me it was merely theoretical, a dream. I couldn’t hold it in a time when hundreds of thousands of people are dying from the corona virus. And people protest the use of masks. And people protest the legitimacy of science. Our forty-fifth president is one of these people. Our forty-fifth president performed violence in plain sight and many cheered and seventy-four million voted for him this past November. Despite his audacious foolishness, his incompetence, his hatred for anyone not wealthy and white and American, many still support him, love him and his violence. The 2020 presidential election was close. It wasn’t a landslide despite despicableness.

Breonna Taylor was killed in her apartment by police officers who weren’t charged with her murder. Amy Cooper, informed and armed with her whiteness and history and the present, performed violence, lied about being assaulted by Christian Cooper, a black bird watcher in Central Park, yet the charges against her were dropped. Derek Chauvin’s knee on George Floyd’s neck: eight minutes, forty-six seconds, Floyd’s murder filmed. Yet if history proves itself as it continues to do, the assailant, the assailants won’t be charged for their actions. No accountability for killing black people. The killers are deemed non-criminal despite protests in the United States and abroad. The expectation is that there will be more black deaths. White supremacy endures its debauchery.

How can I be hopeful in this air, in this moment, where everything seems plainly distorted, grotesque, mapped out horrifically? How can I be hopeful when six Asian-American women are gunned down in Atlanta? Eighty-one million people voted for the forty-sixth president of the United States.

Yet with the former president’s instruction, the capital was stormed, breached by his supporters, domestic terrorists who attempted to kill, maim, harm elected officials. One of the terrorists, one of the insurrectionists carried and waved a confederate battle flag in the Senate building. Yet despite this outrage, 147 Republicans: senators and representatives that evening, after that attempted coup, voted to overturn the forty-sixth president’s fair election.

With headphones on, the same song playing, I watched black and brown leather shoes move about that teal carpet. I watched those inhabiting the shoes vote. I watched their hope to overturn legitimacy and fairness, to overturn truth.

That next morning, as I do every morning, I attempted a poem at my desk. I realized then, unexpectedly, that the hope I thought lost, gone, evaporated, I still possessed; tattered and small, but it was there. The act each morning, the waiting, the listening for, the writing of a stanza or a line of a poem or something that may become such, could possibly emerge with clarity, with veracity even was this small hope of which I cleaved. I understood that I cleaved despite the shambles of the moment and previous moments, despite awareness and experiences. This small thing of language, concentrated and precise, is how I quietly contain myself. It is how I quietly attempt knowledge, truth. I think of Lucille Clifton’s poem, “won’t you celebrate with me”. It is one brimming with hopefulness despite circumstance. There is an invention of a self in that poem despite ruins, war, and ignorance. There is a clear resilience the speaker has and claims. It is the resilience we need now in this moment when uncertainty is perpetual.

This semester I’m teaching a course called, “‘I, too, sing America’ Poetry of this Moment/Moment.” For context, I began the course with the Langston Hughes poem for which the course is named along with Allen Ginsberg’s, “America” and Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing.” We are reading Terrance Hayes’ collection, Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins and Claudia Rankine’s Just Us. We are reading poems that directly speak to this COVID-19 pandemic: poems by Sharon Olds, Fady Joudah, Kamilah Aisha Moon, Ada Limón, and others.

My students are tired, bereft after our discussions. I am too. But this is good for us. It is constructive, particularly at this time, in this time. They say it is difficult to be within two pandemics and read this work not knowing an outcome, a resolution. I explain that feeling this moment, exploring this moment through poetry, even though arduous, even though on Zoom, is a hopeful act. The willingness to be uncomfortable asks us, demands us to improve, to discover what it means to be better humans, to define it, to define ourselves. And that willingness to do so is hopeful. Poetry engages multiplicity, the full self in all of its conflicting fragments.

After four years without artful language or language meant to uplift, the forty-sixth president of the United States opened his term with a young poet in a yellow coat reading her poem.

This evening I’m in the park. I’m sitting on a bench. The sun is setting. The same song blares in my ears. Poetry has brought me here.

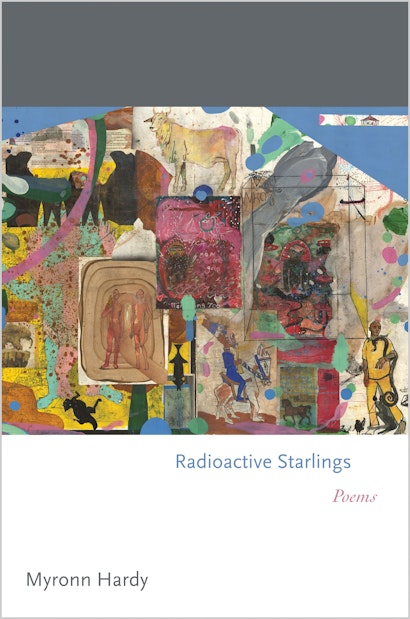

Myronn Hardy is the author of, most recently, Radioactive Starlings, published by Princeton University Press. His poems have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Ploughshares, Michigan Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. He teaches at Bates College.