Most people these days encounter coral only rarely. We might visit an aquarium or natural history museum, watch an environmentalist documentary, read an alarming newspaper report about ocean acidification, or discover what is left of living reefs on a snorkeling or scuba excursion. When we see coral in these places we wonder at its astonishing beauty, of course, even as it inevitably evokes the horror of planetary climate crisis.

As a person who has been writing a book about coral for the past ten years, I have also gotten good at spotting coral in more mundane places: on a glass end table in the lobby of a relative’s seaside condo, on the mantelpiece of a vacation rental with seashell patterned wallpaper, on a shelf in the waiting room of a Midwestern doctor’s office amidst other marine curios intended to establish a general ocean-themed decor.

And so, it seems that, at least in the twenty-first-century popular imagination, coral alternately symbolizes either a blissful day at the beach or the end of our planet as we know it.

In the nineteenth century, however, coral had many other lives.

Somewhat surprisingly, coral was a commonplace part of everyday life and thought for even more people during the nineteenth century than it is today. Reef ecosystems still flourished in the Mediterranean Sea and other warm, shallow waters that most species of coral require. The (then) centuries-old question of whether coral is animal, vegetable, or mineral—or some unique combination thereof—continued to interest natural historians and the public alike. Charles Darwin’s theory of coral reef formation became a topic of international interest well beyond scientific circles from the 1830s onward. Women and girls—wealthy, working-class, and enslaved—wore red coral jewelry supplied by a thriving global coral trade centered in Italy. Some of that Mediterranean coral was exchanged for enslaved persons along the coast of Africa by European traders. And in wealthier families, children might cut their first teeth on red coral: the “coral and bells,” a combination teething aid, toy, and talisman, was a popular christening present.

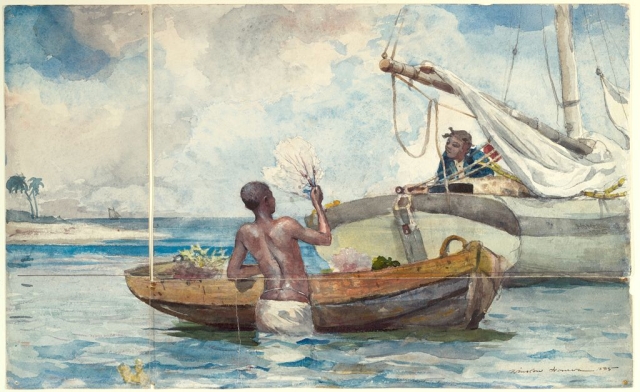

The comparative familiarity with coral during this period seems only to have increased popular interest, curiosity, and wonder. The period’s vast literature, visual art, and music about coral is an endlessly rich guide to the multiple, divergent, complex, and frequently surprising meanings that even the smallest piece of coral once held.

In a song called “The Coral Branch” by Sarah Josepha Hale—“Mary Had a Little Lamb” is her more lasting musical contribution—an encounter with a coral specimen radically transforms the speaker’s understanding of time, history, and human and nonhuman nature. “I thought my branch of coral / a pretty shrub might be,” the song begins. But once the speaker inquires after the nature of coral, the branch that seemed to her like a mere “shrub” turns out to be so much more interesting: coral is not only a plant but also partly animal in nature, the product of a “coral insect”—the period’s popular term for coral polyps—that somehow combines with seawater, plant matter, and millions of other polyps to produce “coral palaces,” the massive structures that we know as reefs. The seemingly lowly and unremarkable coral branch, then, is actually part of a living form so impressively intricate and grand that it boggles the mind. For the speaker (and for generations of Americans who sang the song), enormous questions abound: How do reefs grow? What do they need to live and thrive? If countless tiny polyps collectively produce a reef, then what might humans achieve by working together? The song ends with a revelation: just as coral polyps leave behind a reef that sustains others, “dying, I should leave / Some good work here, / My friends to cheer.” Coral, in other words, teaches us that our only lasting contributions to this world are acts that sustain others long after we die.

Admittedly, not everyone in the nineteenth century found life’s purpose by looking closely and wondering at coral. But some did, and many others—writers, artists, and activists of various identities, political affiliations, intentions, and audiences—found other important meanings there.

Teachers and preachers used the example of coral to instruct listeners that the natural world in all its complexity sometimes defied human systems of taxonomy and classification. For if it was always possible to tell animal from vegetable from mineral, then why had trained naturalists mistaken coral as a mere stone or a plant for centuries before realizing that coral is an animal? The lesson of coral for humans was to have more humility—as one writer put it, to avoid placing too much faith in our own abilities to discern “true nature,” whether human or nonhuman, by external forms (a lesson with clear relevance to our own moment).

During Reconstruction, Black ministers, public speakers, and poets such as Frances Ellen Watkins Harper called upon Black communities to act like coral polyps. They meant that Black people, so long oppressed and excluded from the national structure, despite their essential contributions to it, could now build their own reef communities that would expand like “living stone,” in Harper’s words—that is, by sustaining others rather than devaluing or displacing them.

And for many people coral offered a ready-to-hand lesson in the global supply chain. A number of nineteenth-century poems on coral, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “To A Child” (1845), involve parents reminding their children that red coral is not simply a decoration, teething aid, or toy. Rather, it’s a physical reminder that the luxuries we take for granted may depend on the life-consuming labors of countless others who rarely reap the rewards of their work—in the case of coral, both polyps and persons, including the Mediterranean coral fishers who risked their lives to procure coral from reefs growing on the seafloor, and the coral workers who cut and polished that coral for packing aboard ships destined for the international coral trade.

Why should we bother now to learn these largely forgotten histories of complex human thinking with and about coral? For one thing, they help us realize that coral has almost always been more than biologically important to human life: it has also been conceptually indispensable. There is nothing like coral. As we lose it, we are losing many ideas and insights that only coral can generate.

Relatedly, and just as importantly, historical understandings of coral provide a chance to re-evaluate our present relationships to coral and to the more-than-human world more broadly. It was only possible for coral to offer up so many important lessons during the nineteenth century because people repeatedly approached coral with wonder and inquiry. Coral, however common, never became commonplace. Even, and perhaps especially, when coral appeared to be merely ornamental, it actually compelled people to stop, look closely, ask after its origins, ponder where it came from, how it was made, and by whom or what, and then sometimes use that knowledge to rethink what they thought they knew about themselves and their relation to the more-than-human world.

On a recent trip to Florida to visit my parents, I found myself on one of those touristy streets in a beachside town, kind of like the one I grew up in. The street was lined with shell shops whose windows were crammed unceremoniously with all manner of marine specimens, including those unmistakable branches spreading outward in fantastic forms, though now stilled and lifeless. I’m guessing that most people who buy that coral as a souvenir or decor do not know (or care?) that it’s not some kind of rock, and that it almost definitely came from somewhere halfway across the world—India or a country in the South Pacific are likely places—via a marine curio trade that is often exploitative and poorly regulated, threatening endangered species and marine ecosystems.

Those coral branches still speak to us. Dead and motionless, they explain that planetary climate crisis comes partly from our daily habit of devaluing a living world, of mistaking it for mere ornament. To counteract that habit, we might begin by looking at each part of that world as many who lived before us looked at coral—closely, frequently, and with wonder.

Michele Currie Navakas is Professor of English at Miami University. In addition to Coral Lives, she is also the author of Liquid Landscape: Geography and Settlement at the Edge of Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).