In a mountain town whose name I’ve forgotten, about fifty miles from Marrakech, I remembered an old woman sitting alone in a field. Her legs were crossed. Her face rested in her hands. A Moroccan colleague with whom I was traveling, pointed to her as he walked in her direction. I followed. She was wearing a yellow jellaba and a rag tied over her hair. She had lost her home. She didn’t say how: fire, flood, a beam that randomly crumbled. We sat with her. Most of that time we were silent until her friend walked to her, stretching out her arms to pull the old woman to her feet. Her friend invited all us to her home for tea and dates. She told us, “All would be fine. We will take care of her.” On the drive back to the mountain town where we lived, I asked my colleague, if what the young woman said was merely polite, hopeful-language or actionable truths.

His response, as rocky, dusty land changed to green fields of Canary melons and eucalyptus groves, “No. They will take care of her. This is who we are in Morocco, Alhamdulillah.”

This sense of genuine communal care was the central reason that kept me, sustained me in Morocco for almost a decade. That extension, that stretching of arms, that genuine sense of I care merely because of humanness and proximity. I thought of this at dawn. I thought of this and that old woman as I sat at my desk, at dawn, to write; the practice I’d cultivated, adhered to for years. But on September 9th 2023, at dawn, I began receiving messages that an earthquake, the most severe since 1960, had killed thousands; swallowed, destroyed whole villages as well as well as areas in Marrakech. The earthquake occurred Friday evening.

Out of desperation, out of fear, I attempted to contact all I knew in Morocco. I imagined the worse: tapping emails on the keyboard, tapping numbers on my phone. Nothing was going through or no one was responding. Then there were news reports, one after the other, I was shaking. No one had responded. I thought about the mountain town where I lived for almost a decade. I wondered if the earthquake had been felt there, if it had reached the Middle Atlas Mountains. I sent more emails. I sent more text messages. No one had responded.

I went for a run. It was still quite dark outside but dawn was opening it up: purple sky turned cobalt turned azure, pale sunbeams were coming through. The music playing in my headphones was Nass El Ghiwane. The same Moroccan band I’d played on my morning jogs through the Middle Atlas’ cedar forests.

I wanted to get on an airplane and fly there to check on my friends. I wanted to help. I felt the profound need to help. I wanted to help the place, the people who had so graciously helped me, the exiled me quickly un-exiled. The exiled me who was made to feel at home, necessary, needed, welcomed. But I was on another continent. Both sea and land obstructed.

I thought of that old woman I’d meet in the High Atlas Mountains. I wondered if her new home, those who’d taken her in, were ok. Were they part of the rubble? Were they beneath rocks waiting to be pulled out, rescued? Were my friends alive? Had they been injured? After my run, after my shower, after my breakfast, still no responses. But there was more public news, more images online.

I suddenly remembered standing outside of a mosque in Tinmel, a town in southern Morocco. The structure had been built in the 12th century. It was built of clay, adobe, as many homes, many structures in the Atlas Mountains were/are traditionally built. But there, on my computer screen, it was in ruins. The earthquake had demolished it. It was gone. I kept thinking of all those who prayed there all of those centuries. I kept thinking of all those who’d prayed there on Thursday, the day before it was rubble. I kept thinking of all those who’d been taken, like that mosque, away.

Since moving back to the United States, I’ve had this lingering, longing for the North Africa I knew. The Moroccan ways I’d picked up: the handshake whereby one, after shaking another’s hand, places that same hand over their heart, a way of saying the other remains there; seeking preserved lemons and salt cured black olives in the grocery store; anticipating the first sentence someone new might utter to know which language to use, speak, or to not speak at all, to merely gesture. Sometimes, and by sometimes, I mean rarely, when I’ve heard Darija, Arabic, Tamazight spoken in winter, as snow falls, I’ve stopped, turned around, smiled; grateful I’d been taken back to the snowy-alpine Moroccan town, the sycamore boughs filled with yellow leaves and weighed down with ice. That place where I’d roamed, lived, became this poet with these new eyes, this new language.

The following day, the following dawn, I’d heard from several of my Moroccan friends. They were all ok. A few had experienced some minor damage to their homes, but they were safe. One did say he knew of a family that may have lost several. They were still searching for them. After he’d be told, he held his one-year-old daughter through the night. He couldn’t leave her in her crib despite his wife’s pleading. He needed to know, he needed to feel she was safe and with him. “What’s going to happen?” I asked.

“We will take care of each other. We always do,” he said.

Another Moroccan friend called to say he was ok. He told me that throughout the country they’d anticipated tremors for the new few days, if not through the week. He asked me if I was still waking up at dawn to write.

I laughed. “You remember,” I said.

He laughed, “It’s strange. But it works, right?”

“How do you define works?” I asked.

He laughed, “You’re publishing a new book.”

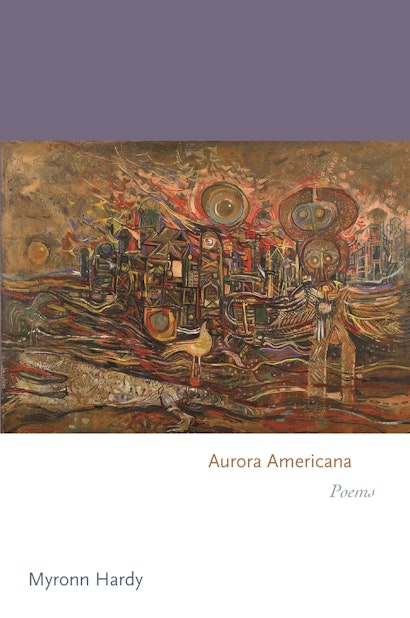

The poems in my new book, Aurora Americana, take place near or at dawn. And they speak to the ideas of dawning and exile. The poems wouldn’t exist without my learning, living in Morocco and that feeling of being exiled in that country, dissipating. Its generosity embraced me.

I find myself standing on sandstone cliffs in Maine watching the Atlantic crash against them. Those sandstone cliffs in Maine, that splashing Atlantic, remined me of the sandstone cliffs where I stood in Morocco watching that same sea break and foam and smooth. But now I’m thinking of the earthquake and how I can’t, now, be there to help. On my many dawn drives to work, I listen to radio reports of the earthquake: more missing, more deaths, more people sleeping outside, in public squares wound in acrylic blankets due to homes destroyed. I’m still thinking of the old woman and her friend I met near Marrakech. Are they ok? Are they taking care of each other? Can they take care of each other when the ground is no longer fixed?

Myronn Hardy is the author of five previous books of poems, including Radioactive Starlings (Princeton). His poems have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Poetry, the New Republic, and the Baffler, among other publications, and have won many prizes, including the PEN Oakland-Josephine Miles Award. He teaches at Bates College.