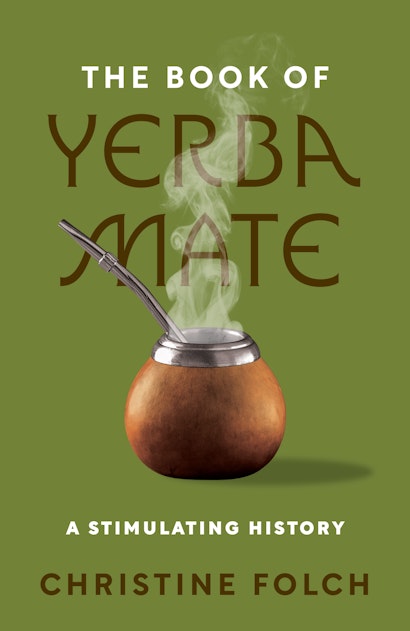

The first time someone from North America tries yerba mate in the traditional style, with a gourd or cattle horn stuffed with smokey green leaves and the metal drinking straw, we often break one of the unwritten rules of the South American drink. We grip the bombilla drinking straw between our fingers as we take a drink. It’s a habit reinforced through oversized sodas at movie theatres or fast food restaurants. But it’s out of place when drinking the stimulating beverage from South America. There’s a reason for not touching the bombilla (rhymes with “tortilla”): wiggle it too much while you’re drinking and you can make it hard for the water to filter down through all the leaves. Yerba mate (YER-bah MAH-teh) is the world’s third most popular naturally stimulating beverage (behind tea and coffee). It’s the drink of choice in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and the southern “gaúcho” Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. Dedicated communities of drinkers in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine arose in the early 20th century. More recently, yerba mate has shown up in trendy Polish cafes in Krakow and Warsaw and in Mormon communities in the United States (where it is permissible unlike the “hot drinks” coffee and tea). And in the last two decades, yerba mate has burst onto mainstream North Atlantic markets as a ready-to-drink canned or bottled brew, having shed the traditional mate gear.

When you woke up today, still groggy and half asleep, what did you turn to for your morning effervescence? If it wasn’t yerba mate, why? It’s not at all obvious why readers living in the Americas or in the circum-Atlantic world should drink coffee (originally from Yemen) or black tea (originally from East Asia), rather than a stimulant commodity beverage that comes from the Americas. After all, when the Spanish were first introduced to the drink in the 1500s, almost no one in Western Europe had even tried a caffeinated beverage, let alone developed fixed stimulant preferences. Iberian colonists learned how to drink yerba mate at the same time that they learned why to drink it. We’re probably not that different.

Made from the dried leaves and tender shoots of Ilex paraguariensis, an evergreen holly that grows only in the Atlantic Forest region in the heart of South America, yerba mate contains a potent combination of three psychoactive alkaloids: caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine. So do coffee, black tea, and chocolate, by the way, but in different proportions. Chocolate (Theobroma cacao) leads the race in theobromine; black tea (Camellia sinensis) has more theophylline per gram than does coffee (Coffea arabica). Black tea also has more caffeine per gram, but coffee tends to have more caffeine per prepared cup. Why? Because of how much raw ingredient is used to prepare an average cup. Yerba mate has a little less caffeine than coffee or tea, but more theobromine and theophylline than coffee. If you’ve noticed that some stimulating beverages tend to suit you more or make you less jittery, it may be a question of how your body interacts with the balance between the three alkaloids.

Our personal body chemistry and the plant’s physical properties are one reason why we drink what we do. But it’s not the only one. Taste is social. It’s not just that we learn to like what we consume (which is especially true about those bitter beverages we call “acquired tastes”); it’s that our taste has an element of public performance to it. French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu conducted a well-known study of the preferences and tastes of French citizens in the middle of the 20th century. He showed them pictures of art, played different kinds of music for them, and asked them about the food they liked to eat and found a surprising trend: our taste, something which feels so individual and intimate, correlates with socioeconomic class status. What this means is that we can aspirationally signal belonging in a group by consuming and liking (or rejecting) a certain kind of food, art, or music. Inside Out, 2 plays up this tendency in one memorable scene where the main character, eager to fit in with the older girls she admires, pretends to not like her favorite band, much to the dismay of her old set of friends. This experience holds true for entire nations, not just tweens in Disney movies.

Yerba mate is so connected to Argentinian, Brazilian gaúcho, Paraguayan, and Uruguayan identities that it is a kind of national drink. Mate does double duty in the regions where it is consumed: it unites, but it also divides. And this is where the idea of the recipe comes in. The three River Plate hispanophone countries that prize yerba have a shared history of Spanish colonialism and then fraught struggles for independence first from the Crown and then from each other and the Brazilian-Portuguese empire just to the north. So, while there might not be one right way to drink yerba mate, there is a typically Paraguayan way to drink it.

Language and accents are a good example here. The rioplatense River Plate form of Spanish spoken in Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay has commonalities that mark it distinct from other dialects of the language, but there are unmistakeable Argentinian, Paraguayan, and Uruguayan accents within in the region. The same is true for yerba mate recipes. Because of how it is processed, the flavor of the yerba sold for Uruguayan palates is slightly, but notably, different from that preferred by Brazilian gaúchos. Even the drinking vessels have different silhouette profiles: a cauttle horn for the ice-cold tereré Paraguayans prefer; a wide-lipped cuia gourd that opens outwards for the chimarrāo style of mate popular in southern Brazil.

There’s a growing attention to recipes as a particular kind of knowledge; for example, recreating ancient dishes as a way to get a better sense of what life was like at a different time, as Nawal Nasrallah did with Akkadian stew recipes engraved onto cuneiform tablets almost four millennia ago. A team of Spanish scientists re-engineered the lost Roman art of making garum, the fish sauce condiment popular throughout the empire. Others claim that what they concocted was not real garum, but liquamen; the former was traditionally made from only the innards and blood while the latter incorporated the entire fish. Modern day disagreements over the right/authentic/best recipes can be another example of the identity politics of consumption, which is why claims to authenticity in cuisine are often not about the food, but power plays about the people behind it. Indeed, Claude Lévi-Strauss and other anthropologists have long been fascinated by what cookery techniques in recipes tell us about *everything*. Back to yerba mate: true, I. paraguariensis has less caffeine than coffee or tea per gram, but yerba mate won’t be outshone. Mate recipes call for nearly half a cup of the dried stuff (or more) to fill the gourds or cattle horns.

Recipes work because they’re ritualistic, iterative, and sit in a time-bending temporality. When we read or hear a recipe, we anticipate a future based on a trusted past. We look ahead with anticipation (the promise of a flavorful dish), but the authority of the recipe comes from having already successfully produced said tasty dish. The fact that recipes rely on multisensory imagination is one reason why recipe books make for such fun recreational reading.

But in the case of yerba mate, the recipe had another effect: the recipe gave rise to the form of economic demand. Spanish colonists learned how to consume I. paraguariensis in the 16th century from Indigenous nations who have enjoyed the plant since time immemorial. As a result of Contact, a creolized recipe for the drink arose even as mate consumption spread along and simultaneously forged imperial trade routes in the Spanish empire from its place of origin in Paraguay to markets outside its growing range in Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Potosí, and Lima. Yerba mate was, literally, money.

The name for the beverage holds this history: the word “yerba” comes from the Spanish for herb or plant. It’s a direct translation from the Guarani term for I. paraguariensis, which they simply and emphatically call “ca’a” (plant). Mate comes the Quechua “mati” for gourd or cup. Many beverages can be taken in a mate: mate de cocais coca (Erythroxylum coca) leaf tea; mate de coco, popular in Paraguay during its brief winter, is a gourd brimming with grated coconut. Spanish speakers in Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay interchangeably use “yerba” and “mate” to denote the dried product, but “mate” also refers to the form of drinking the beverage hot. In Brazil, the expression erva matte is used, but chimarrão (for the brown color of the drink) is more common.

Recipes act as an interface between the social and the material because they intertwine human priorities and the physical or chemical properties of ingredients and cooking techniques. A recipe teaches us how to consume something, not just how to fix it. For a chemically interesting leaf like yerba mate, that includes how to prepare it in order to benefit from the plant’s psychoactive properties. There are many right ways to drink yerba mate. Just keep your fingers off the bombilla.

Christine Folch is the Bacca Foundation Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. She is the author of Hydropolitics: The Itaipu Dam, Sovereignty, and the Engineering of Modern South America (Princeton).