From North America to Asia, and from poor rural areas to cosmopolitan capitals, the far right is having an increased impact on state policies, public debates, and communal life. In recent years, we've grown accustomed to demonstrations featuring white supremacist slogans, campaigns against reproductive rights, and hate speech permeating both online and offline worlds. Electoral polls across the globe prove the popularity of anti-migrant agendas and make evident the appeal of nationalistic claims. And yet, despite the fact the global imaginary seems to be saturated with the image of far-right supporters, we have little knowledge on what makes the far-right offer so attractive to a growing number of people.

One of the reasons is the fact there is no single far right. The term far-right, which I use here to identify those actors that justify their policies and socioeconomic agenda on the basis of nationalism and national belonging, include both proponents of free market and strong welfare state, conservatives and aspiring revolutionaries, professional politicians and grassroots movements. Although in recent years, we tend to pay attention to charismatic politicians that have profoundly impacted the global scene, the role of grassroots mobilization is not to be underestimated and calls for more attention.

As someone who has been conducting ethnography of such grassroots milieus for nearly ten years, I've grown used to the fact that interactions with far-right militants are likely to unsettle many common assumptions about the far right. The first is the problem of—metaphorical and literal—distance that we believe exists between the society at large and far-right proponents. Indeed, the very terms “far” or “radical” presume some sort of distance from the people holding and performing such political views, as well as the fact they operate at the fringes of sociopolitical life. There remains a widespread perception of the far-right supporters either as outcasts belonging to a subculture or as dispossessed and disenfranchised citizens longing for their country’s past “greatness.” And yet, most young people engaging in far-right activism are, to use Hannah Arendt’s expression, “terrifyingly normal”: they study, work and socialize as most their peers do, and devote their free time to activism.

This is not to say that the far right as I got to know it is less dangerous than the one we know from TV coverage on violent rallies. If any, I see the far-right movements as more dangerous than what the mass media images may suggest, in that the factual “work” of the far right, the work that transforms indifferent youth into devoted militants, lies in a series of everyday, grassroots practices. As a matter of fact, the most remarkable thing about the far-right activists and supporters is their ordinariness. For critical observers, it is also the hardest reality to accept, in that it forces us to reconsider the question of distance.

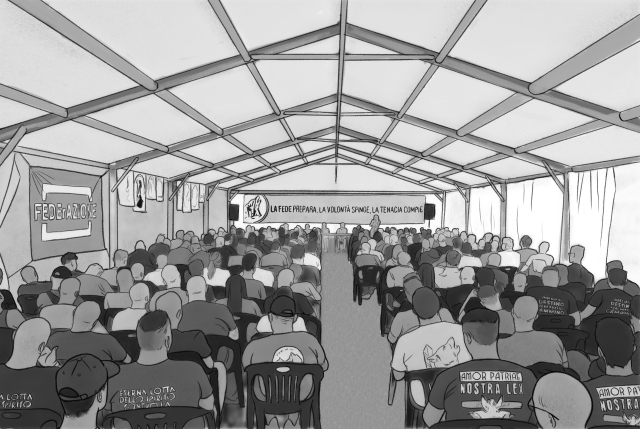

In the course of my ethnographic fieldwork with young Italian, Polish, and Hungarian militants, I zoomed in on such grassroots practices to show why and how young adults join far-right social movements. The movements I have been studying aim to challenge the liberal system and global capitalism, foregrounding the importance of community and collective identities at various levels: from knit-tight communities of militants working together in a run-down neighborhood through nation to transnational community of likeminded people. An opportunity to belong and benefits drawn from belonging appear as key factors behind the militancy. My study further demonstrates that one of the reasons why young people find, join, and remain active in far-right movements, is that such movements provide answers to numerous questions young people are asking. In doing so, it also asks why these are the movements that provide them with such answers.

In highlighting these two aspects—the importance of the far right as a means of belonging and as a source of vocabulary that allow young people to address their concerns—my study challenges some commonsensical takes on the far right mentioned above. I show how a variety of undertakings—from soup kitchen for the poor through sport activities to joint readings—provides a glue for communities of young people from all walks of life. None of these precludes appeal of violence and hateful rhetoric against strangers, which are often reinforced through the emphasis on the obligations towards one's own people. Yet an understanding of the far right is contingent upon acknowledging that few young people join far-right movement because they look for an opportunity to pick up a fight, as well as upon asking why is it that they do not find means of empowerment, self-recognition, and communal bonds elsewhere.

Similarly, while the young people I do research with are attracted not only by a far-right ideology but by its very specific variant, fascism, what they find inspiring in fascism is not necessarily congruent with its commonplace image. To numerous young people in Europe, and their peers elsewhere, fascism stands for a revolutionary doctrine which promised to remake society, to provide an alternative to both communism and capitalism, and to address problems of modernity, primarily, excessive individualism. To them, drawing inspiration from fascism does not aim to restore a past order but to think about future. Again, the recognition of the appeal of fascism forces us to ask questions about a broader ideological landscape and alternatives (or lack thereof). First and foremost, the issues I highlight make evident a need for community and a platform for action that the far right appears to satisfy.

My findings mirror those of numerous ethnographers doing research on various global manifestations of the far right: what tend to trouble us is how “terrifyingly normal” the people we interact with are. It is also a contention we share with historians and philosophers who strove to understand the appeal of and support for fascism and other radical ideologies across different contexts and among varied groups of people. The argument regarding the far right’s ordinariness and proximity is easily contestable, however, and for justified reasons. For members of groups that tend to be key targets of far-right hatred, for educators and anti-discrimination activists, for politicians situating themselves on a different side of the political spectrum, for anyone who simply finds the far-right agendas unacceptable—the idea of the far right’s proximity may feel both implausible and offensive.

I do see the danger in assuming too much proximity or too many similarities, in that such a move may deny the possibility of change and make attempts at countering far-right agendas appear futile. In calling for considering the far-right’s ordinariness and its proximity, I ask whether the claimed distance does not mean a revocation of responsibility. Locating the far right on the “margins” may unwittingly translate into a conviction that the problem is “there”—among the unemployed, disenfranchised, poor. It is not only convenient to locate nationalist, exclusionary sentiments “elsewhere” (in a different time and space), it is also potentially gratifying and self-congratulatory. Just as it is much easier to talk about violent mobs and racist rallies than to denounce the violence of political-economic structures and acknowledge to what extent access to education, healthcare, and opportunity in liberal democracies continue to attest to race and class discrimination. Seen in this light, fighting the far right means, first and foremost, working on how to provide satisfactory answers to the questions that the far right appears to be successfully addressing.