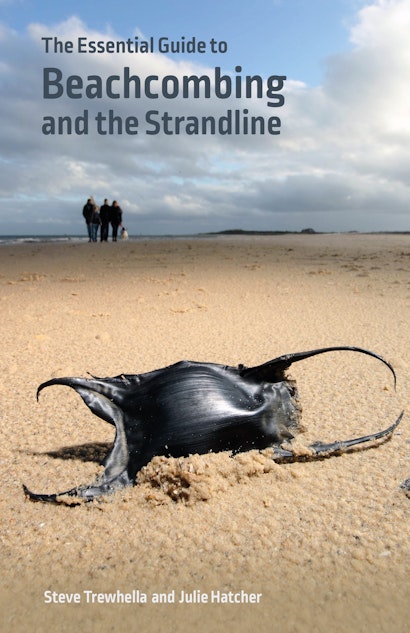

Everything that the sea casts up onto the shore has a story to tell. Some objects give us glimpses into the lives of marine creatures living nearby, others speak of long-distance voyages and a life on the ocean waves, or tell us about our own lives and careless habits. Once you learn to read these stories beachcombing can become an addiction.

The definition of beachcombing is to search for and collect objects such as seashells and driftwood along the seashore. It is an activity people have probably been doing since the dawn of time, whether gathering essential resources such as wood or simply picking up unfamiliar objects out of curiosity. In the Scottish Outer Hebrides, for example, tropical drift seeds, or sea beans, that originate in the Americas and are carried across the Atlantic in ocean currents, were revered for their supposed magical properties and handed down through generations as family heirlooms. Some sea beans are able to float in the sea for up to 20 years finally to wash up on a distant shore still able to germinate and grow.

For some of us beachcombing is a hobby or even a passion. For others it is an occasional pastime—pausing to take a closer look at something that catches your eye as you wander along the shoreline. Whether you are a seasoned beachcomber or an occasional beach stroller the chances are that at some point you have come across something strange along the tideline and wondered what it is and where it came from.

Pleustonic animals, such as By-the-wind sailors and Portuguese Man o’war, live out of sight of land, travelling around the ocean carried by currents and blown by winds. They inhabit the interface between sea and air, half above and half below the water, with poisonous tentacles dangling beneath to catch prey and a sail above to catch the wind. These species exhibit a distinctive colour, blue, pink and mauve, to camouflage them against the sky from animals looking up from below and against the sea from birds looking down. They do not travel alone but are accompanied by a community of highly specialised predators, including violet sea snails and the pelagic nudibranch, Fiona pinnata. By-the-wind sailors can form extensive flotillas and when blown inshore can tinge the beach blue as they wash ashore in vast numbers.

One of the oceanic animals that never ceases to amaze people when found stranded on a beach is the goose barnacle. These bizarre-looking animals can wash ashore in large colonies consisting of many thousands, or singly and in small groups, attached to drifting timbers and litter. With their writhing worm-like stalks and their shell-covered body opening to reveal grasping feeding apparatus they present an other-worldly vision of an animal totally unfamiliar to most people. In fact this animal is a type of crustacean related to the more familiar crabs, shrimps and barnacles we find in rockpools. They have a nomadic lifestyle, settling as larvae on drifting objects in the open ocean and feeding opportunistically on plankton and small surface-living animals as they are carried along in ocean currents.

Beachcombing isn’t just about the rare and unusual and some fascinating finds can be had from closer to home. Mermaid’s purses are the empty egg capsules of sharks and rays and can be identified to the species by their shape and size. Finding and recording these can tell us about the populations of these fish around our shores and even where their important spawning areas are. Empty seashells picked up on the beach often give visual clues as to how the animal died. A perfectly round hole drilled into a sea shell, for example, tells us that the owner fell victim to a predatory sea snail such as a dogwhelk or necklace shell. Using chemicals to dissolve the shell and a hard tongue to scrape a hole through to the soft interior these tiny predators deliver a grisly end for their victims.

Crabs cast off their shell as they grow, separating it from the soft body within and climbing out, leaving a complete moult behind. It looks for all the world like a dead crab lying on the beach. Meanwhile the animal hides away while its skin hardens into a new, larger shell. It can be fun collecting moults from different crab species to compare and identify.

At first glance the rotting piles of seaweed on the beach might not strike you as a valuable wildlife habitat. In reality, there are a myriad of species, ranging from tiny mites and springtails to larger predatory insects which in turn provide rich feeding for small mammals and birds. Ideally only man-made debris should be removed from the beach; driftwood and the rotting carcases of animals provide vital food and shelter for some very rare and often endemic strandline species. If natural objects are being collected ensure that this is limited to one or two specimens, as large-scale removal can be detrimental to this fragile ecosystem.

Unfortunately in recent decades the flotsam and jetsam of our beach strandlines has become dominated by plastic litter, from bottles to bags and fishing net to everyday items such as cigarette lighters, toothbrushes and printer cartridges. Marine litter is a global problem of unimaginable scale and consequence, both to the animals that live in the sea and to ourselves. Cargo spilt from ships, balloon releases, cigarette butts thrown from car windows, disposable barbeques left by uncaring beach visitors and disposable items flushed down toilets—every day more and more of our rubbish enters the sea and precious little is ever removed.

One habit every beachcomber should get into is spending just a few minutes every time they go to the beach removing some of the litter they find. The #2minutebeachclean is a growing movement where beach visitors spend just 2 minutes of their time removing litter and posting photos of their efforts on social media, thus encouraging others to take part.

Beachcombing is an absorbing way to enjoy and learn about the natural world, it is an activity of discovery. It also provides us with an opportunity to make a positive difference to the world around us.

Julie Hatcher is a marine biologist working in marine conservation in Dorset. Her work involves raising awareness of the marine environment and marine and coastal wildlife in the UK, and she has written many articles for newspapers and magazines, as well as designing interpretation panels, posters and leaflets. She also leads guided rockpool rambles and seashore identification training courses, and has been a scuba diver for many years, mostly in the UK. Steve Trewhella is a diver and photographer specialising in British marine life above and below the waves. He is a keen naturalist and when not diving enjoys beachcombing, rockpooling and recording strandline and coastal invertebrates. His beachcombing finds include new species records for the UK and new information about the distribution of wildlife endemic to strandlines. His images are used in publications all over the world and he has worked as a contributor on many natural history television features. His work can be viewed at www.ukcoastalwildlife.co.uk