A confession: for many years I lived a double life—as a writer, anyway. I started as a scholar of the Renaissance and antiquity who loved to cook, to eat, and to taste wine; then, by various happy accidents, I began to receive requests that I actually write about cooking, eating, and tasting wine. After a couple of decades during which I kept scholarly and culinary undertakings sealed off from each other, it began to seem inevitable that I would hook them up, attempting somehow to maintain the rigor of a cultural historian with the attentiveness to pleasure of the gastronome. The result is The Hungry Eye, which demonstrates how the cultural history of Europe from the ancients to the early moderns is inseparable from the story of how people ate and drank.

The Symposium, founding document for everything that we call “Platonic love,” is actually the record of a drinking party, and in another of Plato’s Dialogues (the Gorgias), when Socrates wants to disparage the operations of rhetoric, he refers to it as “cooking,” thus by implication trivializing it. Some Latin poets spend their time targeting the pretensions acted out at formal mealtimes, while others compose invitations to dinner in verse. Pompeii turns out to have been an eater’s paradise with hundreds of fast food joints, and a notable proportion of the city’s excavated objects consists of kitchen and dining room essentials. Once Rome became an empire, public banqueting turned into an instrument of power, and vast amounts of wealth were spent in acquiring gastronomic delicacies from the far reaches of that empire.

The Judeo-Christian world was hardly less culinary. The Bible teaches us that we ate our way into fallen mortality, and it tells stories about the Jews wandering in the desert that put emphasis upon the foods that were available or unavailable. Manna, for instance, is a kind of mystery consumable, variously compared to dew, bread, coriander, honey, and the basis of what we know as middle-eastern pancakes. Jesus famously declared that man does not live by bread alone, but many scenes of his life recounted in the New Testament are mealtimes. Not to mention that an extraordinary number of his parables revolve around edibles—fig trees, mustard seeds, old wine in new bottles, toilers in the vineyard—and that some of his most spectacular miracles involve the feeding of large crowds with limited resources.

In fact, the civilization of Europe from antiquity to the Renaissance (and beyond), whether Christianizing or paganizing, is a non-stop feast. The late antique writer Athenaeus in his Deipnosophistae, composes a fifteen-volume dinner party, and Renaissance grandees design banqueting spaces with scenes of dining and portraits of foodstuffs under the rubric of “honest pleasure,” often in contrast to the realm of dishonest (i.e., sexual, typically adulterous) pleasure. Bartolomeo Sacchi, who eventually became the first prefect of the Vatican Library, produced a comprehensive cookbook under the influence of humanism; it ran through something like fifteen editions in various languages and was followed by a spate of learned texts celebrating the ways and means of cuisine.

The experience of dining is often central to major works of Early Modern European Literature as well. Erasmus composes a series of learned dialogues, called the Colloquies, many of which are scenes of discussion at dinner parties, often with quite specific accounts of foodstuffs; we learn, for instance, that he disliked fish so much that he won a special dispensation that permitted him to consume meat on Fridays. Rabelais’ massive work on Gargantua and Pantagruel is essentially a non-stop account of stupefyingly excessive feasts. And Milton, whose narrative of the Fall of Man in Paradise Lost inevitably makes reference to eating, goes far beyond the requirements of that story, creating a luncheon vignette with Adam, Eve, and the Archangel Raphael, in the course of which the poet strikes a blow against those many theologians who don’t believe that angels eat; when Milton (bashfully) approaches the question of what happens to food after angels eat it, be uses the rather loaded theological term transubstantiate.

Nor, despite the book’s emphasis on the pre-modern, did later ages view food and drink as any less central, as witness the madeleine, which inspires Proust’s entire recollection of his past, or Freud, who declares that the “function of judgment” in the development of the individual dates back to what he calls the oldest of instinctual impulses: “I should like to eat this” vs. “I should like to spit it out.”

We may take all of this to demonstrate something we already knew, a principle I like to call “All stories are stories about food.” But The Hungry Eye aspires to be more than a market basket of instances where eating and drinking form the basis of culture. In the end it’s really a book about aesthetics—that is, the way in which the production and consumption of food, the stories told about feasts, and the representation of human commensality offer themselves as a fundamental site of beauty.

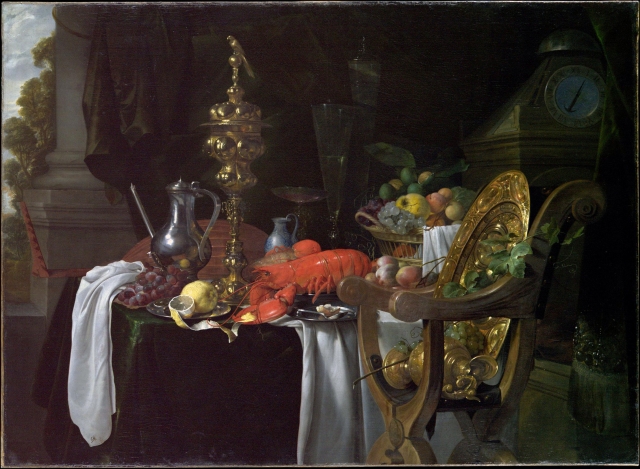

Along these lines, consider the first and the last among the many works of art discussed in the book (and, like all the others, lovingly reproduced, courtesy of Princeton University Press). The Unswept Floor is a 2nd century CE dining room floor mosaic that depicts all the detritus of a feast with near photographic realism—fish skeletons and fins, chicken legs and feet, olive pits, bunches of grapes almost picked clean, the shell remains from a furry urchin. It’s a brilliant visual joke for the diners: as they enter the space of the feast, they seem to have been preceded by an earlier feast whose participants did exactly what they themselves will soon do—that is, throw their food garbage on the floor. It’s a profound joke on both the beauty and the ephemerality of the substances that give us gustatory pleasure and then turn to waste.

Seventeen hundred years later, Paolo Veronese, who was perhaps the supreme master in depicting the major feasts of Christendom, fulfills his commission for the refectory of the Church of Giovanni e Paolo in Venice by producing what he takes to be a representation of the Last Supper. It is, of course, the great subject for the conjunction of art and dining. (The book includes a close study of the foodstuffs illustrated on this occasion, under the rubric “What’s for dinner at the Last Supper?”). Indeed, I argue that it’s the magnetism of this dinner table scene that in a sense hijacks the theology of this moment in the Christian story. After all, in terms of doctrine, the quintessential event on this occasion is Christ’s institution of the sacrament, the declaration that his followers should eat his flesh and drink his blood (“do this in remembrance of me”). But the image that became canonical wasn’t Jesus handing out bread and wine, but rather a group of men having dinner. Veronese, to his cost, seems to have genuinely believed that what he was painting was the grandest of feasts, and when he was brought before the Inquisition to explain himself, he revealed with a kind of real or feigned innocence that he thought his painting was about the organization of a grand banquet, including the carving of the meat and the decidedly lesser activities of a guest with a nosebleed and another picking one’s teeth, doubtless commonplace when the patricians of Venice gathered for a banquet but blasphemous when applied to the Last Supper. He escaped having to change the painting by merely changing its name. But The Hungry Eye insists on the whole spectrum available to the site of dining, its spectacular beauty, its power as a symbol, and its fundamental place in human experience.

Leonard Barkan is the Class of 1943 University Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University. His books include Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures (Princeton), Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture, and Satyr Square: A Year, a Life in Rome. He lives in Princeton, New Jersey. Twitter @LeonardBarkan