Many quintessential dog traits have endured over thousands of years. Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and philosopher from the first century CE, writes about the dog’s loyalty to its master, claiming that it is uniquely capable of knowing when someone is a stranger, recognizing its own name, and remembering how to find distant locations. The seventh-century cleric Isidore of Seville notes that dogs are renowned for their bravery and speed, asserting that they are smarter than other animals. Loyalty, intelligence, bravery and a close connection to human beings – these are all traits commonly associated with dogs today. Similarly, the cat has long been known as mouser-in-chief, managing pest control and occasionally getting into mischief. Medieval manuscripts depict cats tormenting rodents as well as licking their rears (and occasionally doing something more unexpected like churning butter).

Ideas from Pliny and Isidore influenced the content of bestiaries, books about animals that were medieval bestsellers. These texts were filled with descriptions of animals both familiar and exotic, and drew allegorical and religious connections to their alleged behaviours. The fanciest bestiaries were filled with gorgeous illustrations of rare pigments and gold leaf. Some of the animal depictions are familiar to us today, like the phoenix rising from a burning nest of flame, while others are more surprising, like the poor beaver biting off its own testicles to escape from hunters.

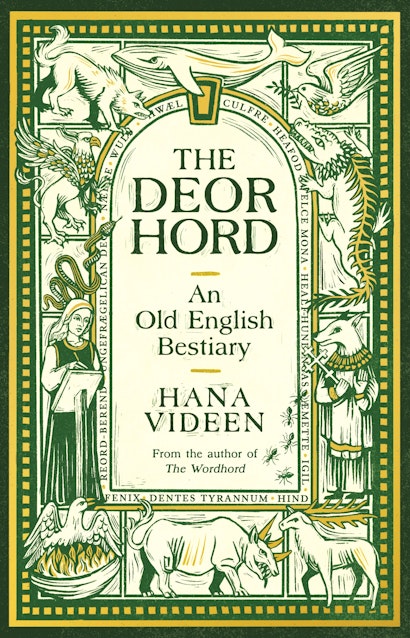

Previously on Ideas I’ve written about Old English, the vernacular language of what is now England from around 550 to 1150. The language was used centuries before the heyday of England’s bestiaries – the twelfth and thirteenth centuries – yet there is no shortage of Old English animal lore. In The Deorhord I have put together my own Old English ‘bestiary’ of sorts. The book’s title is a made-up compound of Old English deor (animal) and hord (hoard), a play upon the actual compound wordhord (a poet’s stockpile of words and phrases).

The words for ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ are virtually the same in Old English – hund (from which we get ‘hound’) and cat or catte (pronounced COT-tuh). There’s also the word docga (pronounced DODGE-ah), more similar to our ‘dog’, but it appears only once in the entire corpus, compared to hund’s 300 occurrences. Cat also appears far less frequently in Old English than hund – only eight times, most of which are in glosses (translations of Latin words for language learners).

Unlike cats, dogs have a variety of terms in Old English: hwelp (‘young dog’ or ‘whelp’), bicce and tife (both meaning ‘female dog’ or ‘bitch’), wæl-hwelp (literally ‘slaughter-whelp’, a hunting dog or dog that kills), wede-hund (mad dog), as well as references to specific breeds, like heahdeor-hund (deerhound), grig-hund (greyhound), roþ-hund (mastiff, pronounced ROTH-HUND) and ræcc (setter). Hundas were useful aids in the work of both the sceap-hyrde (shepherd) and the hunta (hunter), and their byproducts appear in leechbooks (medical texts): blod (blood) for cramping, micgean (urine) for warts, ðost (dung) for nits on children.

Hund is also an insult. In the poem Judith, the wicked general Holofernes is described as hæðenan hund, a heathen hound. This insult happens to be pleasingly alliterative, characteristic of Old English verse, but the connection to heathens is not merely for the sake of poetry. In hagiography the saints call the heathens or pagans who torment them names like un-medoma hund (unworthy dog) and ungeþunggena hund (vile dog). (Un-medoma is the negative of medume, from which we get ‘medium’, which in Old English means ‘middling’ but also ‘fit’, ‘worthy’ or ‘deserving’.)

Hundas can be quite frightening in Old English. A chronicle entry for the year 1127 describes the unfortuitous appearance of demonic hunters when Henry of Poitou was made abbot of Peterborough: ‘their dogs were all black and wide-eyed and loathsome’. These hundes ealle swarte (dogs all black) sound like creatures from hell, and in the Old English translation of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy we encounter an actual helle hund (hell hound), Cerberus, with his þrio heafdu (three heads).

Yet even Cerberus is recognizably (almost adorably) dog-like when Orpheus plays his harp: he begins to onfægnian mid his steorte (show gladness with his tail) and plegian (play) with him. Another familiar canine characteristic is its bark, though in Old English dogs beorcaþ (pronounced BEH-or-koth). Along with their barking, tail-wagging and playfulness, another less pleasant dog trait appears in Old English texts. An abbot warns, ‘The person who renews their wicked deeds after repentance provokes God, and they are like a dog (hund), who vomits (spiwð, pronounced SPEW-ith) and afterwards eats what they before spewed out.’

Hundas, along with catas, are considered un-clæne (unclean) in a way that goes beyond their unfortunate habit of eating their own vomit. Un-clæne animals are animals not fit to be food. Penitentials, texts that list a wide variety of sins and the appropriate judgements to be laid upon offenders, refer to a rule about not touching un-clæne animals when eating. The general opinion seems to be that there are worse things you can do than polluting your food by touching catas and hundas, worse even than accidentally consuming their blood. (In fact, you might find that blod in a medical remedy.)

The fact that cats’ only appearance in Old English is in penitentials and glosses is rather disappointing, but if you are a lover of catas like myself, be cheered by fact that the cat’s bigger cousins – the leo (lion) and panþer (panther) – loom large in the early medieval imagination. A leo (lioness) comes to the aid of St Daria who has been imprisoned in a brothel, and when men come to take advantage of her, she scares them into submission. They are forced to listen to Daria berate them for being less rational than her lioness who – though a mere beast – honours God. Lions are also the companions and symbols of other saints: Mary of Egypt, Gerasimus, Jerome and Mark.

The leo may be the king of beasts, but the panþer symbolises Christ himself. The panþer draws all other animals to him with his sweet-smelling breath and compelling voice and is a friend to all but the serpent or dragon (symbolic of Satan). This behaviour is compared to the way Christ draws the faithful to him with his sweetness and truth. The panþer also eats a big meal before going to sleep in a cave for three days, analogous to the Last Supper, followed by Christ’s crucifixion, burial and resurrection.

Lions and panthers may be the friends of saints, but only the hund has the honour of becoming one – well, a healf-hunding (half-hound) to be more accurate. Known in Latin as a cynocephalus (dog-head), the healf-hunding is a creature that is human except for its head, which is that of a dog. The most famous healf-hunding is St Christopher who has a hundes heafod (dog’s head), sharp teeth, and eyes that shine like the light of the morning star.

The Deorhord gathers animal lore from a variety of Old English sources like these – saints’ lives and Bible verses, sermons and riddles, leechbooks and poetry. There are no chapters about hundas and catas, but you will find stories about creatures as ordinary as a gange-wæfre (spider, literally ‘walker-weaver’) and as marvelous as the fenix (phoenix) – stories that I believe are worth hoarding.

Hana Videen is a writer, a blogger, and the author of The Wordhord: Daily Life in Old English (Princeton). She holds a PhD in Old English from King’s College London, and has been hoarding Old English words since 2013, when she began tweeting one a day. Website: www.oldenglishwordhord.com.