In Pirates and Publishers, Fei-Hsien Wang reveals the unknown social and cultural history of copyright in China from the 1890s through the 1950s, a time of profound sociopolitical changes. Wang draws on a vast range of previously underutilized archival sources to show how copyright was received, appropriated, and practiced in China, within and beyond the legal institutions of the state. Contrary to common belief, copyright was not a problematic doctrine simply imposed on China by foreign powers with little regard for Chinese cultural and social traditions. Shifting the focus from the state legislation of copyright to the daily, on-the-ground negotiations among Chinese authors, publishers, and state agents, Wang presents a more dynamic, nuanced picture of the encounter between Chinese and foreign ideas and customs.

The following interview was originally published here by the Weatherhead East Asia Institute.

What inspired you to write about copyright in modern China?

FW: My parents used to run a small independent publishing house. Growing up as a publisher’s daughter, I have been fascinated by the past and the present of the book from very early on. I first became intrigued by copyright in modern China when I was exploring possible angles to discuss the encounter of late imperial Chinese book culture and the Western modes of knowledge production in late Qing. Modern conception of copyright is considered something emerged (exclusively) from the European print culture, and the conventional wisdom among book historians and legal scholars of China is that China couldn’t develop a strong sense of copyright (and intellectual property alike) because private property and authorial genius haven’t been seriously acknowledged in its tradition. So I thought Chinese understanding of copyright as an alien doctrine might be a good entry point to discuss the encounter and exchange of different systems of textual reproduction and knowledge economy. Very quickly I recalled the various mysterious and suspicious books I have seen in bookshops in Taiwan and China over the years: Made with poor papers and smelly inks, they are likely pirated copies, but they also all stated “copyright is reserved” in their copyright page! My instinct as a publisher’s daughter and a book historian told me that there might be an untold story behind this seemingly paradoxical phenomenon of pirates declaring copyright. And this is how I jumped down the rabbit hole.

Your book begins with a few examples of how copyright law has been circumvented in China. Who are the pirates, what are they pirating, and why?

FW: This is a great question. Although we tend to assume the pirates are shadowy figures operating in the underground economy, most of them in reality operate just like “normal” publishers and manufactures, or oftentimes, as I have shown in my book, they are “normal” publishers and manufactures who infringed others’ copyright for short term profit. Based on my research, I would say that the pirates in China since the late 19th century like to pirate two kinds of books: the new (and often foreign) titles trendy in the market and the provocative ones banned by the government. Taking the advantage of the unfilled demand in marketplace for those titles as well as the customers’ preference of buying cheaper books, these pirates are able to make quick and handsome profit.

Pirates and Publishers discusses the social history of copyright. Can you share an overview of this history? How long has copyright been a part of Chinese law and how has domestic law developed in response to global influences?

FW: The first copyright law in China was promulgated in 1911 by the Qing government. It closely imitated the copyright law of Japan at the time. It was a result of both external pressures and domestic advocates. In the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion, Qing government signed treaties with the United States and Japan to protect specific types of foreign copyrights. European countries also pressured China to join the Berne Convention, an international agreement governing copyright. Meanwhile, Chinese intellectuals and publishers urged the Qing government to issue a domestic copyright law because they believed that (1) it is a law essential for China to become “modern” like others and (2) without a domestic copyright law, Chinese publishers might be in a disadvantaged position when competing with foreign publishers who enjoyed the treaty protection. However, as I pointed out in my book, the treaty clause on international copyright protection was flawed, the Qing government and its successors continuously refused to join the Berne Convention, and, more importantly, the Copyright Law of the Great Qing and its successive laws in the early Republican era never got a chance to be fully implemented due to the limited capacity of the state.

Noting that economic actors might not solely rely on the state and its laws to protect their interests, I shift the focus from state actors and the legislation of copyright to the day-to-day, on-the-ground practices and disputes between authors, publishers, and state agents in the name of banquan/copyright. This approach allows me to unveil a social history of copyright in modern China: Chinese authors and publishers actively invoked what they viewed as copyright to justify their profits, protect their books, and crack down on piracy. Utilizing local legal customs, cultural norms, and civic organizations to achieve their goals, they negotiated and integrated the concept of modern copyright into Chinese business practices, legal regimes, and the social life surrounding book production and book consumption in the early twentieth century, when new knowledge from the West was rapidly commodified and new methods to reproduce information, such as the mechanical letter press, were popularized. Between 1905 and 1958, for example, Chinese booksellers and publishers in Shanghai rejuvenated an old guild, ran their copyright register, settled ownership disputes, and punished pirates. This extra-legal regime was operated parallel to the state’s formal copyright system as most of the time an effective legal framework was absent.

This previous unknown social history of copyright in modern China challenges the conventional view that copyright was “transplanted” to China under the pressure of foreign gunboats. Chinese authors, booksellers, and publishers played a crucial role in its growth and eventual institutionalization in China. While they often presented copyright as an alien and thus modern and universal doctrine, their understandings and practices of copyright were in fact deeply intertwined with and shaped by pre-existing norms and practices in East Asian publishing traditions and cultural economy.

What are your thoughts on the relationship between government censorship and piracy? Wouldn’t a government that aims to have more control printed and digital content embrace and enforce stricter copyright laws that restrict the flow of information?

FW: The relationship between government censorship and piracy in modern China has been a tricky and intriguing one. From late Qing to the present, copyright protection by the state’s law has always attached to government registration— if you want the copyright of your book to be legally recognized, you need to register it at the government. This allows the government to censor the unwanted and inappropriate content, such as pornography and anti-government messages, and as a matter of fact, many publishers and authors in modern China are not against such idea. However, such mechanism couldn’t effectively restrict the flow of “sensitive” information in the early twentieth century because many “inappropriate” books would never be registered at the government and pirating unregistered titles could not be prosecuted by the court because those titles were not copyrighted. So post-publication censorship and political policing became more important for the government. Throughout the early twentieth century (maybe even until today), banned books have always been pirates’ favorite in China. As a result, as I discussed in the book, publishers learned to manipulate the government’s interests in information control for their interests. They accused their pirates not for violating copyright but for circulating subversive contents.

The Communist regime also has been keen (if not keener) in controlling the flow of information, but they took a different approach. Instead of using copyright law as a devise to censor content, they aimed to control the means of production and the circulation of information by nationalizing the media and publishing industry in the 1950s and 60s. For them, piracy would disappear afterward, and it would also become impossible (or extremely difficult) for people to circulate in mass scale unwanted information. Since the 1980s, although the state no longer monopolizes the capacity of mass textual/information reproduction, they still use different kinds of regulations, such as book-number quota or broadcasting license, to control what contents could be released via which kind of media. This for them is far more effective than using copyright law.

What kinds of sources and archives did you consult while conducting research for this book?

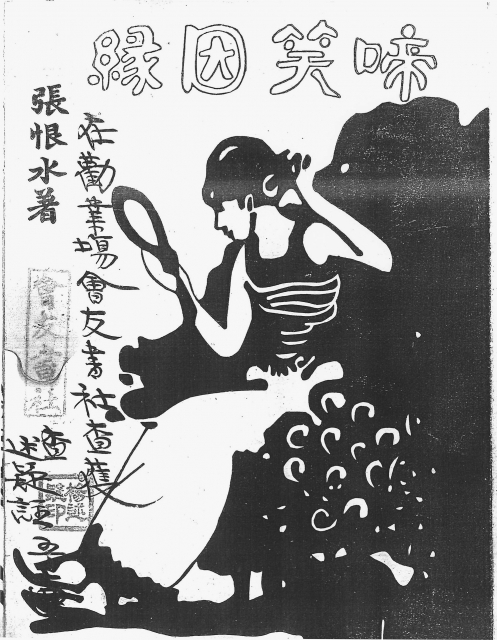

FW: I consulted a wide range of sources during my research for this book, and most of them are not the conventional legal records one would expect to see in a legal history project. Among them, the most crucial one is the archives of Shanghai Booksellers’ Guild. Dating from 1895 to 1958, this rich collection is essential to my reconstruction of Chinese booksellers’ daily operations to establish and maintain a banquan/copyright order in Shanghai, China’s new publishing center, and beyond. To reconstruct howbanquan/copyright was declared, practiced, and negotiated on the ground, I also consulted records of publishing companies, diaries and correspondences of Chinese publishers and authors, government newsletters, book advertisements and public statements in newspapers. Another important body of sources for this book are the actual copies of books published in China between 1890s and 1950s (both the authentic and the pirated ones!) held in libraries in China, Taiwan, United States, and Japan. I examined and discussed them in this book primarily as physical objects that cultural figures/economic actors participated in producing, circulating, and consuming. The information provided and displayed on the physical copies of books, as well as how it was presented, also offers hints about the production process, marketing strategies, and bookmen’s self-identification. As most publishers did not leave personal records or archives, these hints are particularly valuable for us in studying Chinese publishing culture.

What challenges did you encounter in the course of your reading and writing?

FW: One of major challenges I encountered in the course of my research and writing is how to reconstruct the everyday practices and enforcements of copyright in modern China from the fragmented and tedious information scattered in various archive folders, diaries, and correspondences. It’s like making a giant quilt without knowing what the patten should look like as the contexts in which such fragmented information were produced are often obscured for contemporary scholars. It took me a lot of time to reconstruct what might be “common sense” at the time for my historical actors before I can immerse into their world.

Another challenge I faced was that when I decided to extend my discussion to the post-1949 China, some of the archives I was once able to access became unavailable. This unexpected obstacle forced me to modify my plan and learn to read between the lines of restricted materials to uncover the fate of copyright within the communist knowledge economy.

Were you surprised by any of your findings?

FW: Of course. The biggest and maybe most exciting surprise came when I discovered the records of the Detective Branch in the Shanghai Municipal Archives. The Shanghai Booksellers’ Guild, in order to protect their members’ copyright, hired private detectives and established their own anti-piracy policing unit, the Detective Branch. Who would have imagined? Private detectives running around across northern China, setting traps, and raiding pirates? I was completely blown away after I closely reconstructed and examined their daily operations.

Fei-Hsien Wang is assistant professor of history at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is also a research associate at the Centre for History and Economics at the University of Cambridge.