As a child growing up in the then-remote Galapagos Islands, the birds that surrounded my island home—unafraid as they were—fascinated me. Before long I had learned to recognize every species with ease, but it was their oft-surprising behavior and specialized lifestyles that truly captured my imagination. While the total number of resident species may be modest (73, including two introduced ones turned wild), their uniqueness and extraordinary adaptations—to both land and sea—makes their evolution and life histories far more fascinating than their mere identification. How they live and what they do at times can be truly startling, and for over 50 years now, this is what I’ve focused both my photography and my personal observations upon.

It is useful to know that the only way to distinguish between male magnificent and great frigatebirds in the field relies on the purplish, versus greenish, metallic sheens on their respective backs. But how many people realize that their feeding habits are totally different? While the magnificent frigate is a coastal scavenger, the great hunts the high seas, snatching flying-fish on the wing, when these are flushed into flight by other marine predators. Frigatebirds have the largest wing-surface to body-weight ratio of any bird alive. In fact, their hollow bones are so lightly built that an individual’s complete plumage, when taken separately, actually weighs more than its entire skeleton. Despite spending most of their life at sea, frigatebird feathers aren’t waterproof like other seabirds’, so they perform virtually all life functions—except breeding—on the wing: feeding, preening, bathing, sleeping, molting. Some use tropical thunderheads as natural elevators, circling within the cloud to rise to 8,000 ft, from where they can cover huge areas of ocean without exerting a wingbeat.

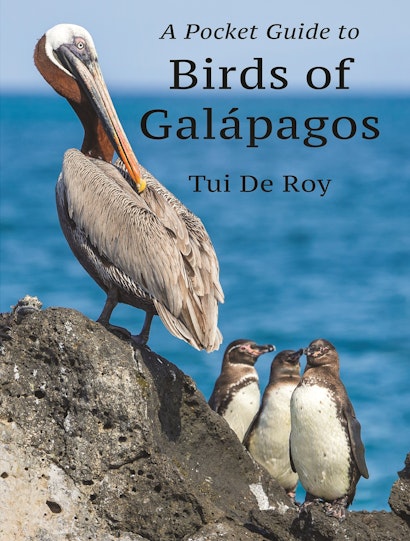

Unique traits among Galapagos birds span both land and sea. For example, while many of the world’s seabird species range widely, using vastly dispersed island groups around to nest, a full 11 of the 18 breeding Galapagos seabirds are endemic at either the species or subspecies level. This includes the rarest gull in the world, the lava gull, with a stable population of around 500 individuals. Flightless cormorants are the largest in their family, having traded flight for unrivalled diving abilities (recorded as deep as 230ft) and spending their entire lives within a few miles of their natal colony—a range they share with the second smallest and only truly tropical penguin, also endemic to Galapagos. On the other hand, with enormous eyes adapted for nocturnal hunting, the swallow-tailed gull flies far out into the Humboldt Current as far south as offshore Peru, along with the waved albatross, the only truly tropical member of the world’s 22 recognized species of these largest of all seabirds.

Unsurprisingly, it is by far within the land bird group that isolation has resulted in the highest degree of evolutionary divergence, as well as behavioral innovations. All but one of the 30 residents in this group (not counting two feral introduced species) can be found nowhere outside of Galapagos. While the most cryptic—and the third flightless species after penguin and cormorant—is the secretive Galapagos rail, the most brilliantly colorful of them all is also endemic: Darwin’s flycatcher (sometimes referred to as the Galapagos vermilion flycatcher), which could often be mistaken, at a glance, not with another bird species but with a red hibiscus flower!

Behavioral surprises abound among Galapagos birds. Flightless cormorants practice sequential polyandry. While leaving their mates to provide food on their own for their growing chicks, females (smaller than males) frequently begin a new breeding cycle with a different male. The hawks too often use a polyandric strategy, but in this case, it is the female who is the larger partner, sharing a year-round territory with up to eight males, all of whom share equal hunting duties and mating privileges in a long-term, stable relationship.

Last but not least come the 17 species collectively known as Darwin’s finches, who break all traditional bounds of identification and biology on many fronts. Deriving from a single ancestor (a wayward tanager of some sort, geneticists tell us), evolution and adaptation have played some funny tricks when evolving in isolation. In practice, this mean that the keen birder must first divorce him or herself from the tried-and-tested notion of color as the main identification feature: with plumages varying from beige to mottled grey to black, or mixtures thereof, the birds’ colors might at best narrow down the options to genus level, but not species—in actual fact, plumage shades more accurately reflect the age and sex of the individual. Likewise for the colors of legs (all of them black) or beaks (which can vary all the way from pale yellow to completely black), which reflect only age and reproductive status but definitely not the species!

The only remaining tools for identification of Darwin’s finches are the shapes and sizes of their respective beaks (which, in themselves, are highly variable). Often more helpful than visual ID is a process of elimination regarding the location of the sighting, since a number of species inhabit just a single island. Even the birds’ songs are confounding, with a high degree of variation from place to place, and even more so from island to island in the case of the more widespread species within the archipelago. Indeed, while studies have shown that the strongest reproductive barriers between species may be the songs that are passed on from fathers to sons, hybridization is quite common.

Evolutionary studies of Darwin’s finches, as so meticulously demonstrated by Drs. Peter and Rosemary Grant, have highlighted some truly astonishing abilities to adapt and change in response to environmental factors within just a few generations. This leaves the observer to ponder whether these innocuous small birds in Galapagos, rather than representing an evolutionary conundrum that defies the accepted rules of character displacement (where similar species living together tend to diverge from each other), may be exhibiting something totally different. Could it be that here is an evolutionary system that works as a sort of ‘genetic melting pot’, where crisscrossing genetic material can serve to re-amalgamate traits as variable environmental conditions offer them a selective advantage?

Finally, if evolution—and therefore the individual identification—of Darwin’s finches can present a few headaches, their inventive behavior is second to none in the bird world. We find little birds that attack much larger birds to drink their blood and that roll their eggs down steep rocks to break them and drink their contents; birds that select, shape and use twigs and cactus spines as tools to hunt insects; birds that elicit a collaborative response from giant tortoises and iguanas to enable them to eat their ticks; birds that specialize in puncturing cactus flowers and fruit; birds with big beaks and small beaks, massive beaks and thin beaks, each one used cleverly for its own special purpose. For the careful observer, the joys of birdwatching in Galapagos are endless.

Tui De Roy is a world-renowned wildlife photographer, writer, and conservationist. A resident of Galápagos since the age of two, she is intimately familiar with its ecosystems and wildlife. She is the author of twenty nature books, including A Lifetime in Galápagos, Galápagos: Islands Born of Fire, and Penguins: The Ultimate Guide (all Princeton).