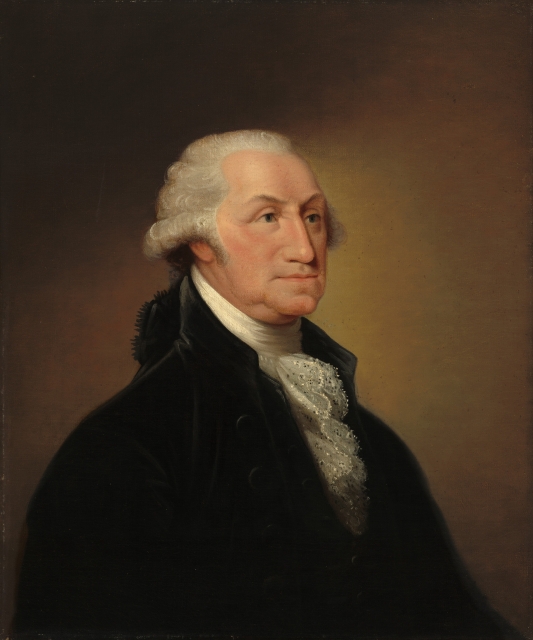

Today is Presidents Day, a holiday established in the late nineteenth century to celebrate the greatest of America’s founders, George Washington. By the end of his life Washington himself was hardly in a celebratory mood when he reflected on the state of the country.

Describing Washington as the greatest of America’s founders will likely raise some hackles—or at least some eyebrows—among historians and history buffs who are partial to other figures of the age, but that is exactly how the other founders themselves regarded him. In fact, Washington’s preeminence seemed self-evident to them. Elections were little more than formalities when he was involved. In 1775 he was the unanimous choice of the Continental Congress to command the Continental Army; in 1787 he was the unanimous choice of the Constitutional Convention to preside over its deliberations; and in both 1789 and 1792 he was the unanimous choice of the presidential electors to occupy the new nation’s highest office. For the first decade and a half of the nation’s independence, the greatest figures in an age full of great figures almost instinctively submitted their wills to his.

As “The Father of His Country,” Washington’s foremost wish for his progeny was that it remain free of political parties and partisanship. All of the founders at least professed an aversion to factions, as they were frequently called—this was a stock theme of eighteenth-century political discourse—but none loathed them more fiercely, consistently, and sincerely than he did. As Washington saw it, partisans are necessarily partial, meaning that they favor the interests of a parochial group over the public good. Partisans could not be true patriots. Parties were also, in his view, fatal to republican government. By sowing conflict, they divided the community and subverted public order; by opposing the government’s actions, they prevented its effective administration; by favoring some over others, they opened the door to political corruption and foreign influence.

To be sure, Washington was not blind to the inevitability of dissent, nor did he believe that it was always wrong for like-minded individuals to band together to further specific ends. But he expected that such alliances would be temporary; when their chosen end was achieved, they would naturally disband and assimilate back into the body politic. The idea of a standing opposition party whose entire purpose was to challenge and resist the administration’s measures filled him with disgust. (If this sounds impossibly naïve, we should recall that the Constitution itself not only makes no mention of political parties, but was devised under the assumption that they would never emerge.)

Whether Washington’s ideal of nonpartisan, disinterested politics was a noble aspiration or a naïve pipe dream, it was one of his fondest hopes for his country, and its disappointment cut him to the core.

To this day Americans are more likely than the citizens of almost any other democracy to echo Washington’s fears and aspirations on this score—to denounce the very idea of political parties and to demand that their politicians rise above mere partisanship. On the other hand, political scientists are quick to point out that parties serve a number of crucial roles in democratic politics: they aggregate and articulate interests, channel politicians’ ambitions, provide an organized locus for dissent, mobilize supporters, structure voters’ choices, and provide collective accountability to those voters. Whether Washington’s ideal of nonpartisan, disinterested politics was a noble aspiration or a naïve pipe dream, it was one of his fondest hopes for his country, and its disappointment cut him to the core.

The political parties that emerged during the 1790s—the Federalists and Republicans—were led by a pair of bitter enemies within Washington’s own Cabinet, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. These were not quite like modern political parties, with their formal mechanisms for selecting candidates, devising platforms, raising money, and waging campaigns, but they were nonetheless recognizable ideological groupings that fought each other with a venom that would make some of the most ardent partisans of today blush.

By 1792, the year in which he reluctantly accepted a second term in the executive mansion, Washington had already begun to bemoan the “internal dissentions” that were “harrowing & tearing our vitals” and making it “difficult, if not impracticable, to manage the Reins of Government or to keep the parts of it together.” Unless the partisan bickering abated, he warned Jefferson, the republic “must, inevitably, be torn asunder.”

When the partisanship did not abate—on the contrary, it grew continually worse over the course of his second term—Washington’s outlook became ever more bleak. He immortalized his worries for posterity in his famous Farewell Address, the great theme of which was the dangers of factionalism in its various guises: political parties, geographic divisions, and the ways in which foreign entanglements exacerbated both. The Farewell is often read as a warning about potential dangers that Washington feared the country might someday face, but it was just as much a lament about ills that he was sure had already beset it.

Washington lived only three years beyond his exit from the presidency, but the state of American politics during his short retirement confirmed his darkest fears. Partisanship reached a fever pitch during the early years of the Adams administration, in the midst of the undeclared “Quasi-War” with France, leading Washington to warn that “party feuds have arisen to such a height, as to … become portensious of the most serious consequences” and that they appeared unlikely to “end at any point short of confusion and anarchy.”

By the summer of 1799 many political minds were already starting to turn toward the next presidential election, and some anxious Federalists implored Washington to allow himself to be drafted once again in order to head off the possibility of a Jefferson administration. Washington’s rebuff was swift and firm, and the reasons that he gave for his refusal were telling: not only would standing for office prevent him from enjoying his much-deserved and long-desired retirement, he was also “thoroughly convinced I should not draw a single vote from the Anti-federal [i.e., Republican] side.” It was no longer individuals and their virtues, Washington lamented, but parties and their ideologies that determined the outcome of elections. “Let that party [i.e., the Republicans] set up a broomstick, and call it a true son of Liberty, a Democrat, or give it any other epithet that will suit their purpose,” he told Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull, “and it will command their votes in toto!”

Read in the context of his lifelong battle against parties and factionalism, this letter reads like an admission of defeat. By this point Washington was convinced that not only Congress but also the American people had become thoroughly and irretrievably partisan. And he had always insisted, since his days at the head of the Continental Army, that republican government could not survive for long under such conditions. Just weeks before his death, Washington wrote to James McHenry, his former secretary of war: “I have, for sometime past, viewed the political concerns of the United States with an anxious, and painful eye. They appear to me, to be moving by hasty strides to some awful crisis; but in what they will result—that Being, who sees, foresees, and directs all things, alone can tell.”

Washington was far from the only founder to grow disillusioned with America’s political order. Indeed, my forthcoming book, Fears of a Setting Sun, argues that virtually all of the founders who lived into the nineteenth century came to feel deep anxiety, disappointment, and even despair about the government and the nation that they had helped to create. As the founding generation’s leading figure, however, Washington’s disillusionment is particularly striking. In his own view, his political career represented something like the reverse of his military career: in politics he won most of the battles—the elections, the policy disputes—only to lose the broader war.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is professor of political science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. His books include The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought (Princeton). He lives in Cazenovia, New York.