Which are the keywords of our time? Black, Brexit, Climate, Trans? New words, old words that have changed, words that have switched users and come to mean different things from before. Words bristling with an energy that bespeaks the concerns and aspirations of our age.

Could grace be a keyword of our time? Sung and written about in a multitude of contexts, it denotes a certain something we look for not just in the Christian church but in law courts across the globe, on catwalks and the silver screen, in our writers, politicians and artists. It can be geographically anchored, unlocking the specificities of a particular place. Take American grace, for example, as explored in Robert D. Puttnam and David E. Campbell’s American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us (2012). Grace, here, encapsulates the bedrock of shared values that permits America to be at once deeply religious and religiously diverse. Grace, imply the authors, is largely responsible for the consistency of interfaith tolerance and social cohesion, despite the so-called culture wars dividing the United States. Yet, I would suggest that since that book, the situation has changed. Grace has become more of a battleground, a contested term in those very culture wars it was thought to transcend.

Remember June 26th, 2016, when Barack Obama delivered in Charleston a eulogy at the funeral of the Honourable Reverend Clementa Pinckney? One of the most rhetorically polished speeches of his career, the eulogy was also one of his most outspoken. Commending and mourning the graciousness of his friend, shot dead in church alongside eight of his congregation by a white supremacist, Obama employed in his eulogy a rhetoric of grace to lambast the ‘unique mayhem of gun violence’. Invoking the eighteenth-century hymn, which he later went on to sing, he praised the amazing grace that permitted America now to see that it had been blind to the perfidious racism corroding its social fabric. In that context, grace was a powerful tool of persuasion, deployed not only to describe Pinckney’s character and the consolation Obama wished for the Charleston community in the wake of their tragedy, but also to expose and decry the greatest challenges facing twenty-first-century America. We were still in the era, then, when grace could be used by a president of the United States to unite opponents, to urge a coming together to tackle shared problems for the common good.

Fast forward to the 2019 Amazon-sponsored TV series, Trump by Grace, where grace is deployed differently for divisive political ends. Privately financed, this highly unsuccessful series sets out to claim grace for itself, reinventing it as the rightful property of only one class of American. Trump by Grace follows the story of a middle-class Irish American, mourning the loss of his wife to the opioid epidemic. In an opening monologue, the protagonist declares ‘our shared passions bonded us. We were Christians, conservatives, who believed in God, family and country’. With his next breath, he makes clear that these are passions shared by Donald Trump as well, but not so much by Hilary Clinton. Nor, indeed, are they the primary concerns of politicians from any gender, race or creed other than Donald Trump’s. America was in ‘darkness’ under Obama, O’Leary opines, Donald Trump is ‘the light and the hope’. Faced with the unspeakable prospect that Clinton might win the 2016 presidential election, our protagonist contemplates abandoning his beloved America. But before he does, he donates money to the Trump campaign and: ‘I decided to do what I do best: I prayed, I prayed and I prayed’. The rest of the vanity project unfolds just as you might expect: moving through episodes called ‘Socialism and Suicide’, ‘Omnipotence’ and ‘Illusions’, it culminates in ‘Answered Prayers’, when the protagonist obtains his dual reward of Trump-as-president and grace.

Why compare Obama’s oratorical skill with a resoundingly graceless TV flop? Because the comparison exemplifies the semantic range of ‘grace’, the high political stakes involved in contemporary American usage, and the degree to which focusing on the term reveals much about our shared concerns and divisions. I have been particularly alert to such revelations during the writing of my book, The Grace of the Italian Renaissance. The book examines a very different time and place, but the ability of grace to travel to the heart of the most pressing social and cultural issues remains the same, then as now. It is the sense that 16th-century Italian grace becomes ever more relevant to our 21st-century lives that inspires, at least in part, my study.

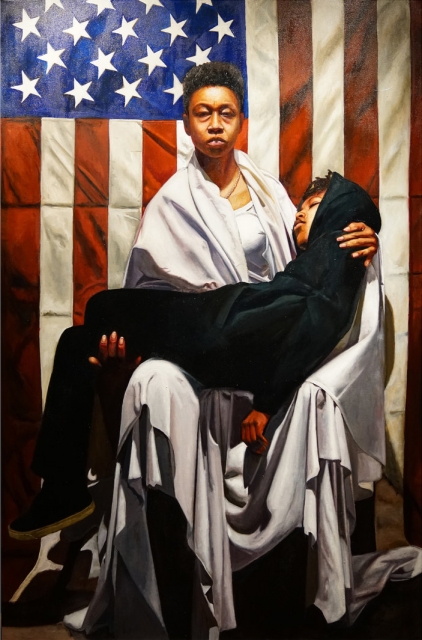

The most famous case study of Renaissance grace is undoubtedly to be found in Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier (published 1525), but there are others who make grace their own. Michelangelo’s Pietà, translated so powerfully for modern America in the painting by Tylonn J. Sawyer, is another intensely personal study of grace (thanks to Tylonn for granting his permission to use the image). But The Book of the Courtier holds especial appeal for the students I teach year on year, invoking the perfect Renaissance scene as it records conversations purportedly held in the beautiful ducal palace of hill-top Urbino at the turn of the sixteenth century. Over the course of four spring evenings, figures from the nobility gather in the fine hall overlooking the rugged Marches landscape to discuss the characteristics that most distinguish the perfect courtier and lady-at-court. Key to excellence, they concur, is the quality of grace, which Castiglione’s speakers describe in a variety of ways. Clearly hard to define, grace is finally pinned down by one of the speakers, who offers his ‘universal rule’. For Ludovico da Canossa, grace is the nonchalant art of concealing the effort behind hard work and study, the opposite of trying too hard. It is the icing on the cake, the certain something that makes everything we say and do – no matter how hard-won – seem easy. This is the grace familiar to millennials and generation Z. Yet true grace, they learn from Castiglione, is not all about performance. The show is far from everything, and it is the underlying hard work and study that really count. Unlike the ‘fake it till you make it’ mantra so often marketed to generation Z, Castiglione’s ideal grace is not the façade to conceal one’s feelings of lack, but a front that dissembles the wealth of knowledge and hard work required to excel at anything. Moreover, grace is not true grace if motivated by popularity- and success-seeking alone. Making friends and influencing people by effecting nonchalance is not grace but mere sycophancy and idle flattery. Grace, by contrast, is directed towards a ‘good end’, towards a common goal as well as personal gain.

Castiglione offers a different mode of operation to generation Z, a different creed to the world leaders they will vote for and become. This alternative mode of operation values the hard work that goes into excellence as much as the nonchalance that makes it all look easy. It recognises that grace must be cultivated for the public as well as the personal good. In this and many other respects, it is indeed a keyword for our times.

Ita Mac Carthy is associate professor of Italian and translation studies in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at Durham University. Her books include Cognitive Confusions: Dreams, Delusions and Illusions in Early Modern Culture, Renaissance Keywords, and Women and the Making of Poetry in Ariosto’s “Orlando furioso.”