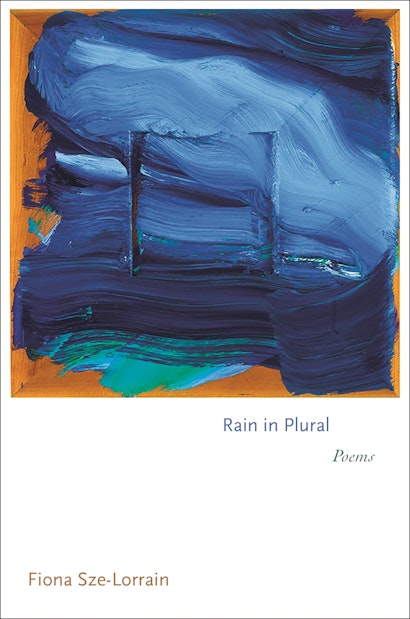

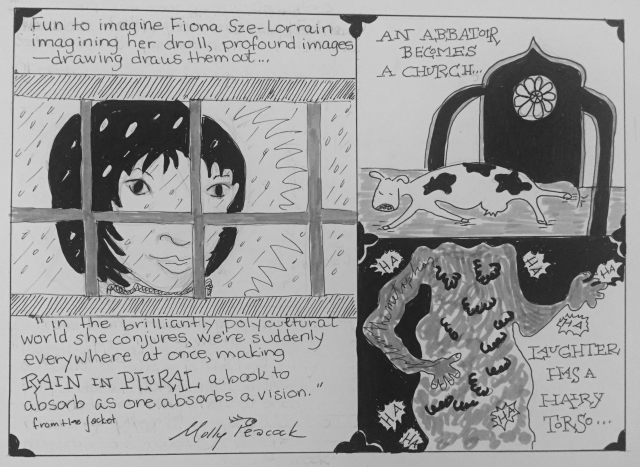

Rain in Plural is the much-anticipated fourth collection of poetry by Fiona Sze-Lorrain, who has been praised by The Rumpus as “a master of musicality and enlightening allusions.” In the wholly original world of these poems, Sze-Lorrain addresses both private narratives and the overexposed discourse of the polis, using silence and montage, lyric and antilyric, to envision what she calls “creating between liberties.” With a moral precision embracing us without eschewing I, she rethinks questions of citizenship, the selections of sensory memory, and, by extension, the tether of word and image to the actual.

Poems are spirit stones. Or suiseki, 水石. Musical notes, stones.

*

Starting point:

back to the basics—how, when, why, what, who, and where.

As simple and bare as possible.

*

I call this phase the foundation, the “basement”—and stay there as long as possible, in spite of the heat. I go to this basement as if I were practicing a ritual.

*

My poems believe in austerity, efficiency, and the possibilites of “under-promise, over-delivery.” Neither American nor Chinese, or Russian, in terms of their politics or foreign policy, given the current temperature.

*

My poems can’t stand small talk or discourse, and style and rhetoric. From the ending section of a sequence piece in this collection:

To quote Solzhenitsyn, Blah blah blah …

Tsvetaeva, Nnh, nnh, nnh …

I delete violence from words that fly too soon.

—“Not Meant as Poems”

*

In lieu of unusual times, how about lousy times.

*

I could not write poetry during our imposed confinement in France. Not even a word.

Then the next question, What did you do?

*

A black sun, not the moon, leads me to insomnia.

*

Is there something wrong with maintaining poetic anger?

*

If criticism isn’t a sin or crime, why doesn’t poetry criticize or defy more, especially when there exist risks or consequences?

*

Some writers and politicians aren’t frank because they think that is poetry.

*

I still read different translations of Buddhist scriptures and listen to Soviet pianist Richter’s Bach, Liszt, and Szymanowski. I, too, read Einstein and maps from the forties.

*

The book does not carry a dedication. I wish it did. The one to whom it hopes to be dedicated makes it clear that this is how it should be.

*

My poems go naked when they laugh. Even in Greenland.

*

Stories bore me, which in part explains why I am such a poor storyteller. In poetry I invest more in the liminality of emotions, and don’t put much faith in psychologies.

*

Identity politics is a form of consumerism, which is why in poetry it becomes capitalist and bourgeois.

*

Rain in Plural is about the urgency of living in plural—being collective, not generic. To Individualism [in whatever pronoun you manifest]: here is not the place, but you are welcome if you make an effort.

*

This might sound Japanese instead of French: “the” is being preferred over any pronoun and the [in this case, its] implied sense of ownership or control. Le, la, les … la-la-la.

*

In terms of subject matter, my poems do not confuse strength with power.

They don’t hide mistakes, but their ego must be tamed.

*

Back to nature—

with little colored, and a plant pushed to the left of a blue jay in a picture.

*

I don’t want to be a poet. I would like to be many poets and stay human.

*

Anywhere could run / as a a sequel / or pattern / or an abstract play / in various languages. […] Cities digested, / heavens downloaded.

*

One may find in this collection poems about dissidents, Charlie Hebdo, Brexit, tyrants … and a link to WeTransfer.

*

Because it is hard to give up beauty—

*

Yes, stones eternalize rigor. Leaves each a longing in the wind, a painting, an act, a line—an honor.

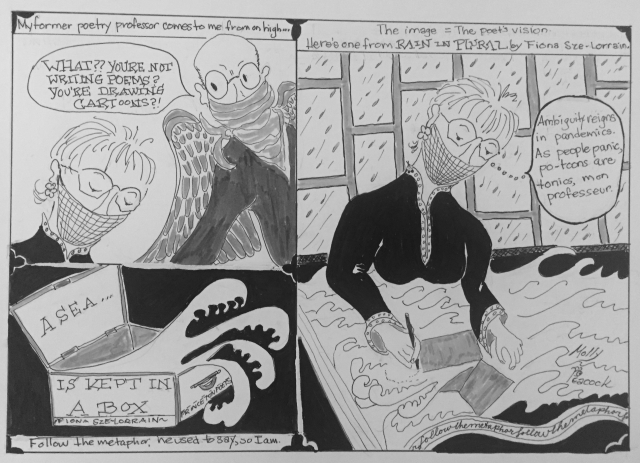

Through the cartoon lens

Fiona Sze-Lorrain is a poet, translator, editor, and zheng harpist. She is the author of three previous poetry collections, including The Ruined Elegance (Princeton), which was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She has also translated more than a dozen books of contemporary Chinese, French, and American poetry. She lives in Paris.