In 1961 James Baldwin found himself in the studios of WBAI radio in New York, looking into the eyes of Malcolm X. Malcolm was, by then, the most recognizable face associated with the Nation of Islam (NOI), a religious sect that was inspiring hope in the hearts of some and fear in the hearts of others. In his role as the leading “witness” of the black liberation struggle – “my job is to write it all down” – Baldwin had been keeping a close eye on the NOI. Baldwin was intrigued by the fact that law enforcement officers did not seem to know how to stop NOI ministers from preaching and he was impressed, as he explained later, by the sect’s ability “to do what generations of welfare workers and committees and resolutions and reports and housing projects and playgrounds have failed to do: to heal and redeem drunkards and junkies, to convert people who have come out of prison and to keep them out, to keep men chaste and women virtuous, and to invest both the male and the female with a pride and a serenity that hang about them like an unfailing light.”

“I would like to think of myself as being able to face whatever it is I have to face as me, without having my identity dependent on something that finally has to be believed.”

James Baldwin

And yet, one of the central things Baldwin wanted to get across in his conversation with Malcolm was that the minister’s theology was suspect. Baldwin was sure to point out that NOI theology was no more suspect than any other theology, but it was suspect nonetheless. By way of explanation, Baldwin presented Malcolm and the listening audience with what he described as a “reckless” idea: “I would like to think of myself as being able to face whatever it is I have to face as me, without having my identity dependent on something that finally has to be believed.”

This “reckless” idea captures, in a nutshell, Baldwin’s radical philosophy and politics of identity. The question of identity was always at the forefront of Baldwin’s mind because he believed it was the question at the core of every moral conundrum and political controversy. Through the lives of his fictional characters and the subjects of his nonfictional writings, Baldwin returned again and again to the same set of questions. What identities do we construct for ourselves and for the communities of which we are a part? How do the identities we construct lead us to treat other people? What in these identities is true and what is false and how can we tell the difference?

From Baldwin’s point of view, most human beings, most of the time are in thrall to false identities they have constructed in order to give themselves the illusion of safety. One of the primary tools we use in our quest for self-definition is differentiation from other people. More often than not, we seek to use differentiation as a lever by which we can feel superior to others in one way or another. It is here that we find the roots for what Baldwin called our “passion for categorization” and our desperate desire to have all aspects of our lives “neatly fitted into pegs.”

With that general diagnosis of human beings in mind, it is not difficult to see why Baldwin viewed NOI theology as “suspect.” The NOI relied upon a philosophy of differentiation as the centerpiece of its conception of identity. As noted above, Baldwin was impressed with the NOI’s success in providing people with a greater sense of self-respect, power, and freedom in the world. But the price paid for this sense of identity, Baldwin argued, was far too high. The NOI relied on ideas that Baldwin viewed as fundamentally inimical to human dignity and so he felt compelled to call out the sect for promoting a program that was ultimately “suspect” and even, Baldwin said later, “sinister.”

It is important to note that Baldwin’s critique was not limited to NOI. Indeed, Baldwin thought of the NOI as merely one manifestation of a deeper ailment with the American soul. While many responded to the NOI with shock and disbelief, Baldwin saw the sect as an expression of something quintessentially American. So much of American mythology, Baldwin explained, relied on just the sort of formula being put to use by the NOI: self-definition by way of differentiation and claims to supremacy. “I am very much concerned that American Negroes achieve their freedom,” Baldwin wrote later, but “I am also concerned for their dignity, for the health of their souls, and must oppose any attempt that Negroes may make to do to others what has been done to them.”

In the place of false constructions of identity that lead us to view one another as less than human, Baldwin called on us to embrace the reckless idea of confronting the world as ourselves.

In the place of false constructions of identity that lead us to view one another as less than human, Baldwin called on us to embrace the reckless idea of confronting the world as ourselves. Baldwin’s radical philosophy of individuality requires that we engage in constant introspection so we might be able to detect when we are relying on labeling and categorization in order to make ourselves feel superior to others. Without this sort of introspection, we may occasionally lull ourselves into a sense of safety, but it will keep us from being free. This sort of freedom, Baldwin said later, is “hard to bear,” but it is the only freedom worth having.

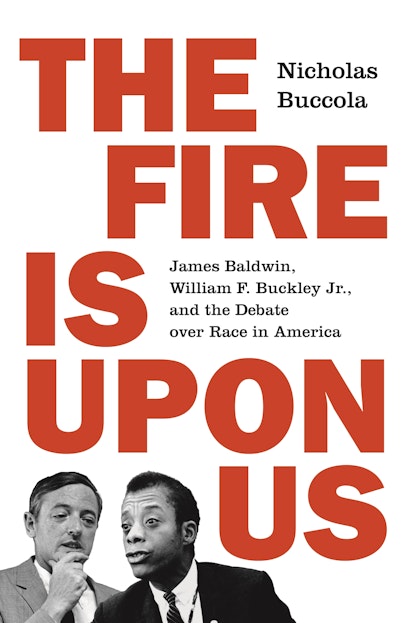

Nicholas Buccola is the author of The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass and the editor of The Essential Douglass and Abraham Lincoln and Liberal Democracy. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Salon, and many other publications. He is the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, and lives in Portland.